The Mulberry Gardens and the German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface in Whitechapel

By Survey of London, on 18 September 2020

Immediately south-east of Altab Ali Park in Whitechapel is Mulberry Street, a short quiet back street the west end of which is anchored by the strikingly tall bell-tower of the German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, a building of 1959–60. This blogpost presents the church in the context of the longer and previously untold history of its site.

The Mulberry Gardens, south-east of Whitechapel parish church, in the 1740s (extract from John Rocque’s map of London of 1746, courtesy of Layers of London and The British Library)

An approximately four-acre quadrilateral of ground lying south of present-day Mulberry Street was a mulberry plantation, laid out with paths in a grid. Mulberries had been introduced to London by the Romans and were commonly used for making medieval ‘murrey’ (sweet pottage) as well as for medicinal purposes, but there is no basis here for supposing such early origins. The neatly planned grove may have arisen from James I’s attempt to establish native silk production in 1607–9 when around 10,000 saplings were imported and distributed by William Stallenge and François Verton through local officials at six shillings for a hundred plants, less for packets of seeds. Mulberry gardens thus came about across England, echoes of the King’s own of four acres in the grounds of St James’s Palace. The commercial project failed, black mulberries (Morus nigra) having been acquired rather than the white (Morus alba) that silkworms tend to favour, somewhat mysteriously as this choice cannot have been made in ignorance. There was a second mulberry garden close by, across Whitechapel Road in Mile End New Town, north of what is now Old Montague Street and east of Greatorex (formerly Great Garden) Street. Land to the east of that south of Old Montague Street appears also to have been similarly planted. Spitalfields was already at the beginning of the seventeenth century a centre of silk throwing and weaving. Peter Coles has written a history of London’s mulberries.

Whitechapel’s so-designated mulberry garden, like that at the palace, eventually fell to use as a pleasure ground. But there was an intervening period of use as a market garden. Around 1679, Giles Kinchin, a Ratcliff gardener, appears to have been granted a lease of the property by Stepney manor. John Martyr, an apprentice who married Kinchin’s widow, Ann, in 1705 succeeded as the site’s proprietor. The property passed to stepson William Kinchin in 1723, but the gardening venture failed and in 1728 the younger Kinchin’s brother-in-law Rowland Stagg took over, thereafter adapting the premises to be a pleasure ground. There was a garden house near the north end and recreational use continued up to at least 1760, when the arrest of four young gamblers by Sir John Fielding’s runners was indicative of anxieties about the presence of vice. An executed pirate refused burial elsewhere was interred in the otherwise disused grounds in 1762.

Engraved view of the encampment of German refugees in the Mulberry Gardens in 1764 (courtesy of London Metropolitan Archives)

The Mulberry Garden ‘behind Whitechapel Church’ was made new use of for a few weeks in late 1764 as a temporary asylum, a tented camp for around 400 deceived and destitute refugees from the Palatinate and Bohemia who had been abandoned on what they had undertaken as a journey to Nova Scotia. Helped by exhortations to charity and by local people, notably other Germans, in particular the Rev. Dr Gustav Anton Wachsel, the first pastor at the German Lutheran Church of St George on Alie Street, the refugees were able after all to depart and, following a petition to King George III, to settle in South Carolina. The garden remained untenanted until 1772 when John Holloway, a Goodman’s Fields cooper, acquired freehold possession of the property and adjoining lands (about 4.5 acres in all) from Stepney manor for building.

The former Mulberry Gardens as built up from 1784 (extract from Richard Horwood’s map of London of 1799, courtesy of Layers of London and The British Library)

Under Holloway’s ownership streets were laid out from 1784 with more than 150 humble two- and three-storey houses, up by the 1790s on leases of from sixty-one to eighty-one years. Union Street was formed as a widening and continuation of Windmill Alley, a passage from Whitechapel Road. What had been a rope walk to the east became Plumber’s Row, probably because a property at the north end of its west side pertained to Alderman Sir William Plomer. Great Holloway Street and Little Holloway Street ran east–west roughly on the present line of Coke Street, and Mulberry Street crossed as what is now Weyhill Road continuing north to a small open space that John Prier laid out as Sion Square in 1788–9. The Mulberry Tree public house stood on the north side of Little Holloway Street where greater density was interposed with the formation from 1788 of Chapel Court between Union Street and Mulberry Street; that finished up in the twentieth century as Synagogue Place. Holloway’s estate as a whole was sold off at auction in 1839.

Sion and Chapel as place names in the late 1780s have their explanation in the early adaptation of an attempt to sustain the allures of the locality as a pleasure ground. A large site on the east side of Union Street, 100ft by 160ft, was taken in June 1785 on an eighty-one year lease by George Jones, a ‘riding master’, in partnership with James Jones. The Joneses built premises that were a riding school by day and an entertainment venue in the evenings. These opened in April 1786 as Jones’s Equestrian Amphitheatre, an almost circular polygon of about 100ft diameter with galleries on a ring of columns for a capacity audience of 3,000 under a copper-covered dome. The venue incorporated scenery and machinery, and its ceiling was decorated with ‘painted palm-trees and other forms’. [1] Shows at this early circus displayed ‘a great variety of incomparable horsemanship, and various other feats of manly activity’. [2] With William Parker, George Jones also held leases on the north side of Union Row (present-day Mulberry Street) including the Union Flag public house. Across Union Street a six-house quasi-crescent mirrored the amphitheatre’s shape. The circus venture folded in April 1788, perhaps on account of licensing difficulties, with a send-off that included non-equestrian acts from Sadler’s Wells and Philip Astley’s Royal Grove. Astley’s Riding School and Charles Hughes’s rival Royal Circus, Equestrian and Philharmonic Academy, both close to Westminster Bridge on the Surrey side, had probably inspired if not actually produced the Joneses in the first place.

At its closure the amphitheatre had been let for conversion to use as a chapel for the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion. Founded in 1783 as a dissenting denomination, the Connexion had already converted another circular pleasure pavilion, the Spa Fields Pantheon in Clerkenwell. In 1790 the Union Street building became the Sion (or Zion) Methodist Chapel, a stronghold of Calvinistic Methodism that had its own school.

London’s German Catholic Mission acquired Lady Huntingdon’s Sion Chapel in 1861. This congregation, unique in England, had its origins in 1808 at the Virginia Street Chapel, just south of Whitechapel in Wapping. There were thousands of German Catholics in the area, largely employed in sugar refining. A year later the mission moved to premises in the City that were dedicated to SS Peter and Boniface, the last appropriate as having gone to Germany as an English missionary (born Wynfrid).

German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, interior of the building of 1873–5, as extended in 1882, photographed c.1900 (courtesy of London Metropolitan Archives)

In 1862 the former circus building was given a thorough refit in a Romanesque style, work overseen by F. Sang that included an 18ft-wide Caen stone altar. At the opening the Rev. Dr Henry Edward Manning preached and Cardinal Wiseman blessed the church. A section of the building east of the amphitheatre was adapted for the mission’s school in 1870–1. Then, in May 1873, the old theatre suffered a spectacular collapse of its domical ceiling and had to be cleared. Manning helped Father Victor Fick raise funds for a replacement building. A German Gothic scheme by E. W. Pugin (who had prepared plans for a building for the Mission in 1859–60) was superseded by a loosely Romanesque design from John Young, that style preferred by Manning who attended the opening in 1875. In front of a basilican brick church, a square west tower bore Royal Arms, an overt proclamation of loyalty, and came to incorporate a mosaic of 1887 showing St Boniface preaching. Set back from the street, the church was gradually enclosed by later brick structures by Young in a similar manner. There was the addition of a presbytery to the south in 1877, a northern school range in 1879, and eastwards extension of the church with an apse and enhanced interior decoration in 1882, this carried through by Father Henry Volk and justified on the grounds of a growing immigrant congregation. Stained-glass windows and wooden Stations of the Cross were of German origin. There were further works in 1885, when bells made at the neighbouring Whitechapel Bell Foundry were added to the tower. In 1897 Father Joseph Verres gained approval for the formation of a covered playground below a schoolroom and sanitary block to the north-east. More improvements and an extension of this block followed in 1907–8 and 1912–13.

Dispersal and expulsion of members of the congregation aside, St Boniface suffered heavily the consequences of Britain’s wars with Germany. Damaged in a Zeppelin raid in 1917 and having been confiscated as enemy property, the church passed in 1919 into the ownership of the Catholic Archdiocese of Westminster. Consecration followed in 1925 when Father Joseph Simml was installed as priest. Then a high-explosive bomb destroyed the church in September 1940. Simml, an opponent of Fascism, stayed through the war, sometimes preaching in the open air. The congregation retreated to the easterly school buildings.

Rebuilding was pursued after the war despite the loss of much of what had been left of the congregation to more salubrious parts of London. Some remained willing to travel to Whitechapel, and from 1949 there were also new immigrants, predominantly women, many from East Germany drawn to work in factories, hospitals and homes, for education or through marriage, sometimes to British soldiers of the post-war occupation. Some German prisoners of war also stayed on. War-damage assessment was handled for the Archdiocese by Plaskett Marshall & Son, architects, who prepared a conservatively historicist scheme for a new church in 1947. Without funding this was premature, but on archdiocesan advice the firm was kept on. Upon the death of the senior partner, his son, Donald Plaskett Marshall, took control through Plaskett Marshall & Partners; he worked extensively for the Roman Catholic Church in its London diocese in the 1950s.

Model for the rebuilding of the Church of St Boniface to designs by Toni Hermanns, as displayed in 1954 (photograph courtesy of TU Dortmund, Baukunstarchiv NRW) and as surviving (photograph courtesy of the parish of St Boniface)

From 1952 the rebuilding was pursued by Father Felix Leushacke (1913–1997), thinking big in anticipation of future growth and working with Simml, who brought a liking for Bavarian Baroque to the project. Alongside war-damage compensation there was to be financial help from the West German government. The first plans for the new building disappointed Leushacke so in 1954 he involved a German architect and friend, Toni Hermanns of Cleves (Leushacke’s birthplace). Hermanns visited the site, prepared numerous possibilities in sketches and then presented worked-up plans and a model that were photographed and published. The model and preliminary sketches survive at the church. Hermanns, a strongly imaginative architect best known for the Liebfrauenkirche in Duisburg of 1958–60, proposed a cuboid block, to be lit by numerous small round windows in a radiating pattern on a long west (liturgical south) elevation. The Archdiocese vetoed the scheme – Leushacke quoted its response as ‘Never!’, upon which Plaskett Marshall said (an assertion that he was to remain in control in Leushacke’s view), ‘And now you leave the dirty work to me!’ [3] Plaskett Marshall worked up revised plans in close if fraught consultation with Leushacke in 1955–6, encountering many more objections from Bishop George Craven at Westminster. The scheme was settled with approval from the newly installed Archbishop William Godfrey in 1957 after debate over the cubic or auditory nature of the main space, progressively non-processional for a Catholic congregation at this date. Higgs & Hill Ltd undertook construction beginning in November 1959 and the new Church of St Boniface opened in November 1960, Cardinal Godfrey being present at both the start of work and the opening. A building of some architectural panache, the Church of St Boniface is unlike other work by Plaskett Marshall and does seem in significant measure to reflect Hermanns’s approach and aesthetic, though Hermanns was not involved after 1954. Wynfrid House, a guest house of 1968–70 adjoining to the east and also by Plaskett Marshall, supplies a telling comparison.

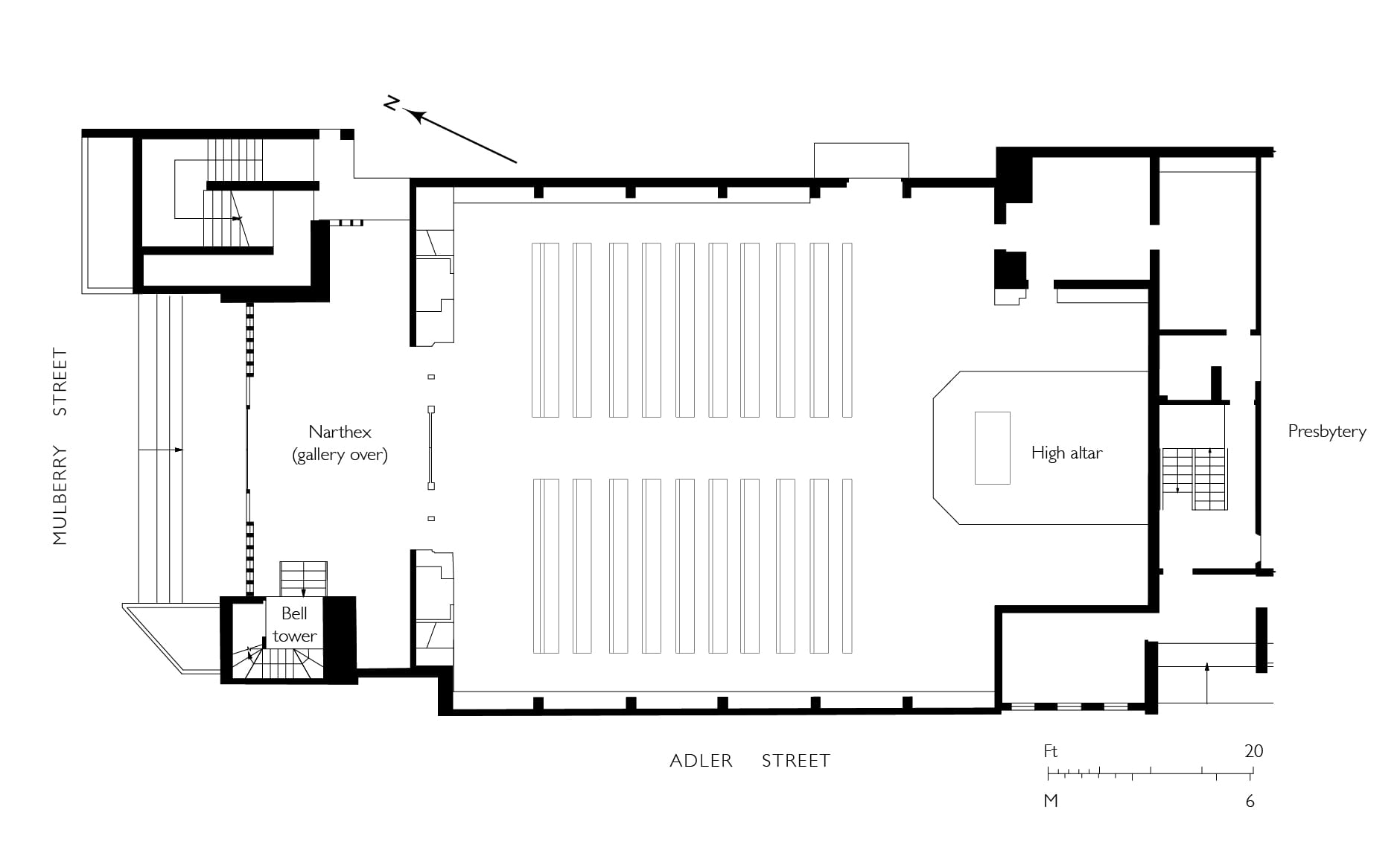

German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, Mulberry Street, Whitechapel, in 2003 (photograph by Jonathan Bailey for English Heritage, © Historic England Archive) and ground plan (drawing by Helen Jones for the Survey of London)

The church has a concrete encased steel portal-frame structure. The main walls are of hand-made dark-brown bricks rising to a clerestorey. Above, concrete eaves, cast (unusually) on plastic-lined shuttering for a coffered effect, underlie a copper roof that was supplied by the Ruberoid Co. Ltd. The upper-storey of a Westwerk is faced with small coloured-glass windows in a grid of black mosaic crosses on a yellow ground. The south-west tower rises 130ft and is clad with concrete slabs faced with grey-scale patterning in ceramic mosaics. At its top an open belfry houses the salvaged locally made Victorian bells. This slender and prominent landmark tower was chosen in an either-or situation in preference to central heating, toilets and a vestry room, prestige trumping comfort. The building as a whole is remarkable for the richness, originality and elegance of its decoration. The plain three-storey presbytery to the south facing Adler Street, habitable by 1962, contrasts with ochre two-inch bricks.

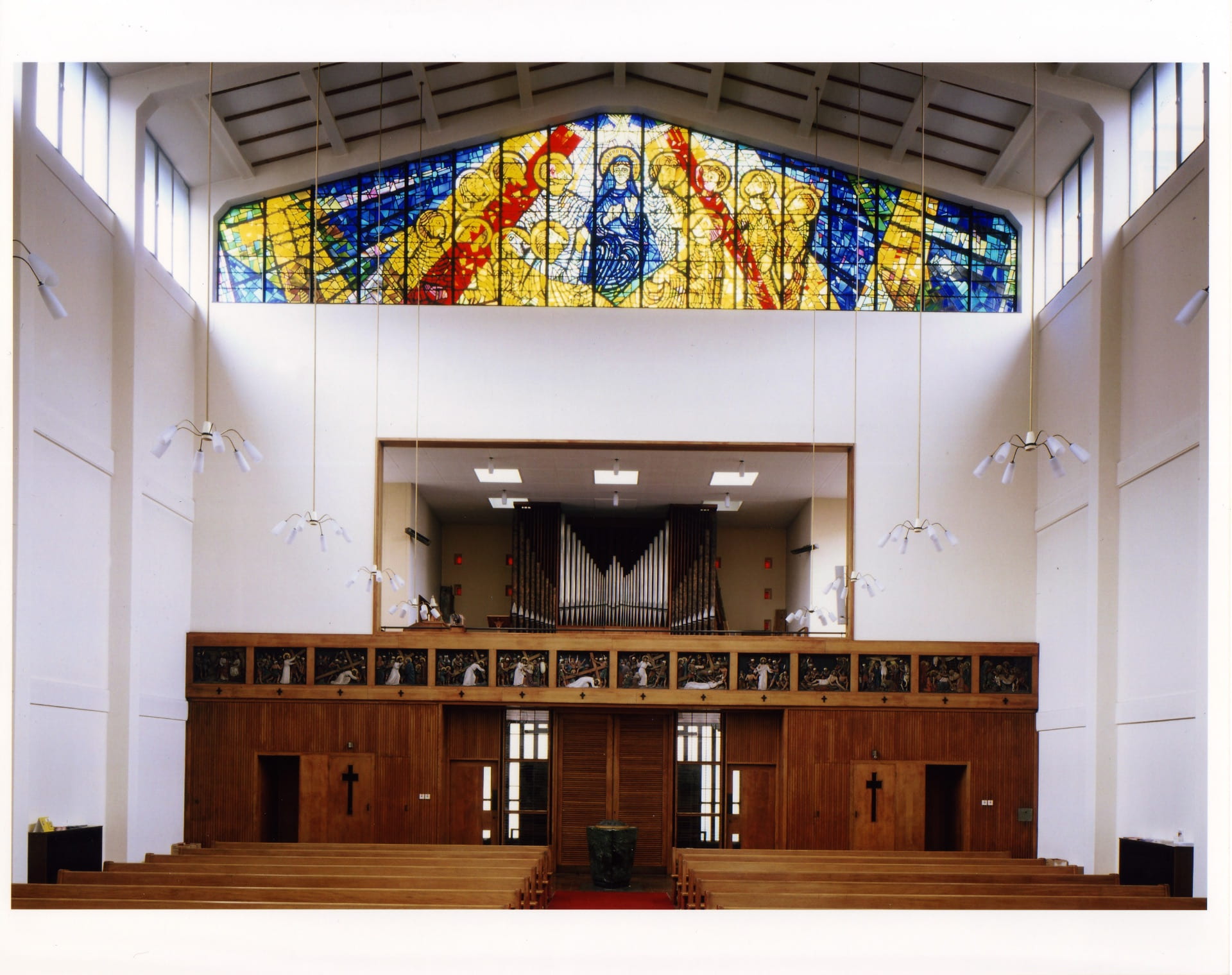

German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface, interior views in 2003, showing the south (liturgical east) end (top), and north (liturgical west) end (bottom) (photographs by Jonathan Bailey for English Heritage, © Historic England Archive)

The church interior is spacious and light, generally white in its surfaces setting off fittings and stained glass of distinction. Within a timber-lined narthex, it provided seatings for 200 in the nave and sixty in a north gallery. The high altar, Lady Altar, tabernacle plinth, and a quasi-triangular font are all of a dark green marble, with a chancel floor of white Sicilian marble, enlarged after the Second Vatican Council of 1962–5. On the south (liturgical east) wall there is a large sgrafitto mural of Christ in Glory above St Boniface preaching to the faithful, made by Heribert Reul of Kevelaer, which is near Cleves. Figurative and decorative wrought iron is by Reginald Lloyd of Bideford, Devon – four panels (altar rails resited as a kind of reredos in the post-Vatican II reordering of the sanctuary) and a gallery front depicting the Crucifixion with the Nativity and the Resurrection. An ambo or pulpit front depicting the parable of the sower has been removed since 2003. There is a lectern of 1980, made by Lloyd to mark the thirteenth centenary of St Boniface’s birth in Devon. The font has a bronze cover commemorating Simml (d. 1976), also by Reul. To the north (liturgical west) the gallery front has the Stations of the Cross, relief carvings from Oberammergau (by Georg Lang selig Erben), eleven of fourteen dating from 1912 and reused from the old church. Romanus Seifert & Sohn made the organ in 1965. A spectacular stained-glass window by Lloyd above the gallery depicts Pentecost. The congregation began to disperse and dwindle and since the 1970s the church has been shared with a Maltese community.

1 – The Builder, 4 October 1862, p. 713

2 – Morning Herald, 20 April 1786

3 – Felix Leushacke, ‘Memorandum über Damalige Umstände beim Wiederaufbau des Anwesens der deutschen katholischen Mission in den Jahren 1958/60 für St Bonifatius-Kirche und Pfarrhaus und 1968/70 für das Gemeindezentrum Wynfrid-Haus in London Whitechapel’, 1993, typescript held in the parish archive at the Church of St Boniface, p. 3

One Response to “The Mulberry Gardens and the German Roman Catholic Church of St Boniface in Whitechapel”

- 1

Close

Close

Thank you for this fascinating article about St Boniface, German Catholic Church in Whitechapel. It is of great interest to me. My Great Grandparents were married here in 1889 and later their subsequent children baptised. The internal photograph is particularly appreciated.