Frascati’s Restaurant, 26–32 Oxford Street

By Survey of London, on 26 June 2020

Our latest blog post is the third piece in a series of extracts from the Survey of London’s volume 53, on Oxford Street, published in April 2020. This piece includes four photographs of Frascati’s Restaurant by Bedford Lemere & Co., making use of a new facility on the Historic England Archive’s online catalogue. We are aware that these photographs might not appear for users of the Safari web browser and recommend using an alternative such as Google Chrome.

Once among the West End’s most famous restaurants, Frascati’s operated in spacious premises behind 26–32 Oxford Street between 1892 and 1954. Frascati’s had a chequered early history. It emerged from plans to redevelop the former Star Brewery to the west of the Oxford Music Hall. By 1887 the brewery had been acquired by a speculating mine owner, R. B. Lavery, on whose behalf a builder, J. Evans, applied to erect shops and offices at Nos 26–28. Briefly that scheme was superseded by a plan for a music-hall-type ‘theatre and opera house’, for which the theatrical manager and entrepreneur Andrew Melville was to act with Lavery as sponsor. Designs for this so-called New Oxford Street Theatre came from the Birmingham architects Essex & Nicol, with whom Melville had been working in the Midlands. Two versions were sent in to the Metropolitan Board of Works in quick succession during the summer of 1887. The first included a show front in Franco-Flemish style towards Oxford Street and a three-tiered, east-facing auditorium behind with a refreshment room and promenade serving each floor. The revised version, incorporating better exits and more up-to-date iron construction for the roof and cantilevered balconies, won approval. But Melville must have backed out, for nothing more is heard of the theatre.

The eastern end of Oxford Street c.1870 (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland)

In about 1888–9 the front block at 26–32 Oxford Street was erected in carcase. This severe, four-storey brick building was probably the work of the City-based architect J. Lewis Holmes, once more representing Lavery. It included generous entrances in the centre and east position, reserved for whatever would be built behind. In 1889 Holmes brought forward plans for a grand café to fill the back space, with Henry McDowell, an art dealer and entrepreneur of New Bond Street, as the prospective tenant. The project was spatially ambitious, involving an iron and glass structure behind the existing block of Oxford Street shops, centred upon an octagonal dome 40ft in diameter and overlooked by deep galleries, to which there was separate staircase access. Though the design was somewhat crude and old-fashioned, it seems to have been largely built, and a music licence was obtained for the prospective Frascati Winter Garden. But when McDowell asked in March 1890 to extend the licence to selling alcohol, the London County Council, by then the pertinent authority, declined, pointing out that the original licence had been granted on condition that the building was not to be a music hall or casino with a bar attached. The refusal led to McDowell’s withdrawal, leaving the structure untenanted.

Oxford Street, looking west c.1900, with Frascati’s Restaurant in the foreground to the right (Postcard in possession of the Survey of London)

A more exotic taker now came to the fore in the person of A. W. Krasnapolsky, a Dutch businessman of Ukrainian descent. Krasnapolsky had risen to fame by creating a fashionable café and winter garden in the heart of Amsterdam, enhanced by electric lighting. Drawn to London and the Frascati’s site, he commissioned elaborate alterations from the well-known Dutch architect Jan Springer. These were in the planning stage by the end of 1890, and in hand during the summer of 1891, when it was reported that Dutch carpenters were on site despite a lock-out in the London building trades. Representing Springer in London was his assistant Willem Kromhout, later an architect of greater distinction than Springer; a third designer of note, Alban Chambon, a Belgian who had previously contributed to various London theatre interiors, was also involved. Under the hands of these collaborators the structure was fitted out and enriched in a florid Renaissance taste. The Krasnapolsky Restaurant, now so called, was inaugurated by the Dutch ambassador, Count de Bylandt, at the end of November. It was advertised for its winter garden, billiard tables and lager beers; a painting of the young Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands by Hubert Vos held pride of place. Besides the winter garden behind, it took in most of the front block at 26–32 Oxford Street.

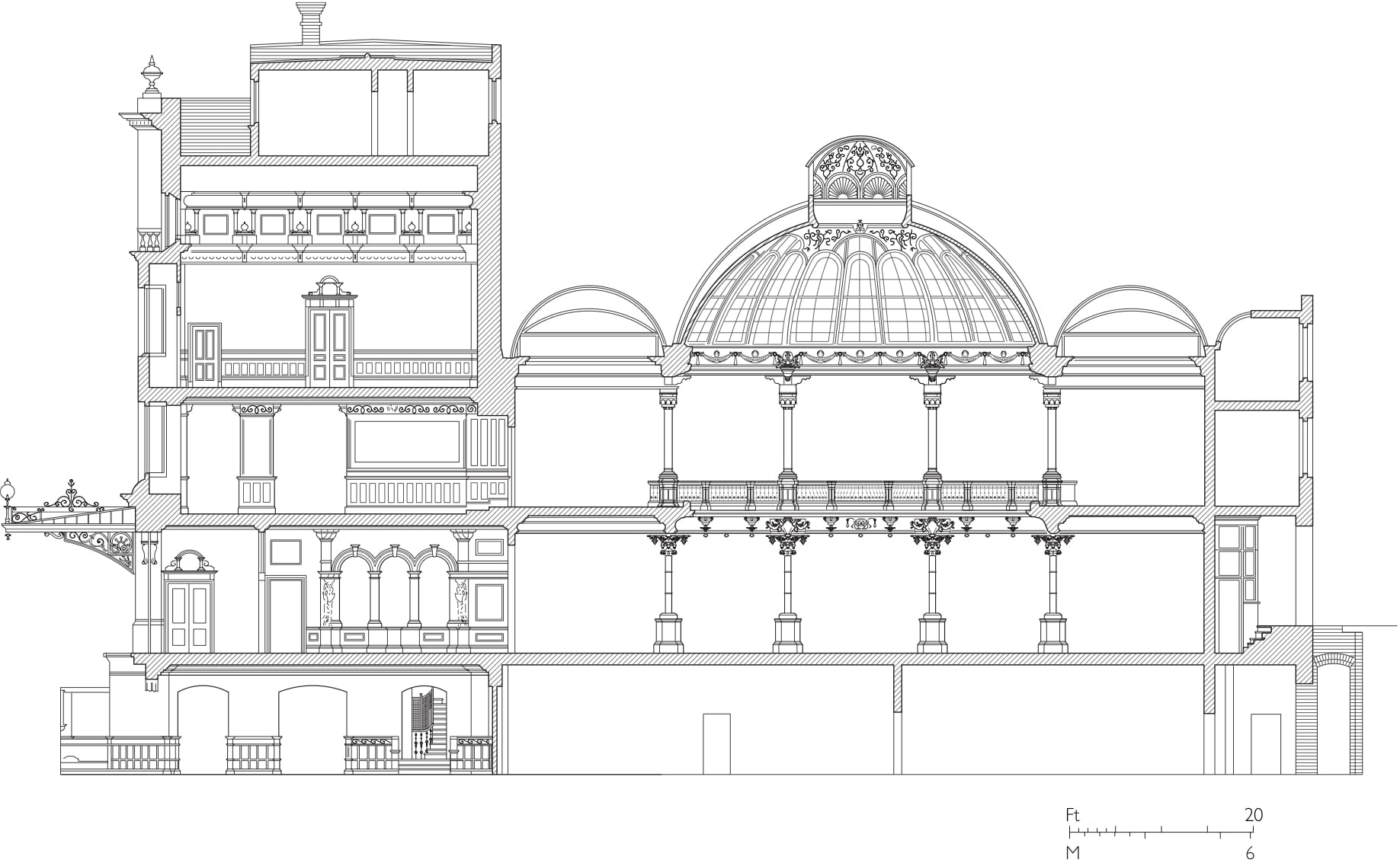

Frascati’s Restaurant, section, c.1905 (drawn by Helen Jones for the Survey of London). Please click on the illustration to open an expanded version.

But Krasnapolsky had miscalculated. Too much money was spent (according to one source £100,000) and too little arrived from Holland. Within six months the restaurant was in trouble and the creditors were closing in. The business was sold in the summer of 1892 to the proprietors of the Holborn Restaurant for £70,000, who reinstated the name of Frascati’s. The enterprise now began to flourish at last.

Frascati’s Restaurant, plans, c.1905 (drawn by Helen Jones for the Survey of London)

The Holborn Restaurant stood formerly on the south side of High Holborn, about half a mile east of Frascati’s. Founded in 1874, it flourished under the management of Thomas Hamp as a large-scale establishment for the professional classes. In the mid 1880s the hotelier Frederick Gordon bought the Holborn and doubled it in size. Hamp remained in charge, and probably initiated the acquisition of Frascati’s. At any rate a company under his name was responsible for minor decorative alterations early in 1893. These were limited, the essential arrangements and décor having been created by the Krasnapolsky designers. The facilities at this stage consisted of two large billiard rooms in the Oxford Street basement, a buffet and marble-lined grill room on the ground floor above, and the large domed winter garden behind. To one side was an elliptical alcove, perhaps for the orchestra, and on the other a kitchen. Two ample curving stairs led up to balcony level, where the Alpha Saloon occupied half of the front. Above again were an opulent Banqueting Hall and the earliest of what was to be a series of masonic rooms. But the winter garden was the space everyone remembered. ‘There are gold and silver everywhere’, noted the restaurant critic Col. Newnham-Davis:

The pillars which support the balcony, and from that spring up again to the roof, are gilt, and have silver angels at their capitals. There are gilt rails to the balcony, which runs, as in a circus, round the great octagonal building; the alcoves that stretch back seem to be all gold and mirrors and electric light. What is not gold or shining glass is either light buff or delicate grey, and electric globes in profusion, palms, bronze statuettes and a great dome of green glass and gilding all go to make a gorgeous setting.[1]

Like the Holborn, Frascati’s earned its way by hosting private dinners for clubs, companies and associations. If its fare was not of the highest class, it was remembered for the élan of its central space and for the pleasures of dining there to the accompaniment of a string orchestra, not yet usual in 1890s London. An early aficionado remarked,

Frascati’s really does supply a perfectly innocent and a rational plan of recreation to a class of persons … who never enter ordinary so called Music Halls. It provides an orchestra solely, without songs or any scenic attractions, and hence is the one place of entertainment in this immense city of its kind … There are many who like myself dine at clubs or elsewhere, and like to saunter in afterwards to smoke a cigar and hear some pleasant music.[2]

Winter Garden at the Krasnapolsky Restaurant in 1892 (Historic England Archive). If the photograph is not visible, please switch to another browser such as Google Chrome.

The various minor changes made to Frascati’s during the mid 1890s were probably designed by T. E. Collcutt. Fashionable just then in the West End on the strength of his Imperial Institute, his extensions to the Savoy Hotel and his opera house at Cambridge Circus, Collcutt was a neighbour to the Hamp family in Bloomsbury Square, and in 1894 was commissioned to aggrandize the Holborn Restaurant with the King’s Hall. He also designed an iron and glass canopy for the Frascati’s entrance at 32 Oxford Street, but it was refused permission by the LCC. In 1895 Frederick Gordon gave up his controlling interest in the two establishments, which were reorganized as a public company, Holborn and Frascati Ltd. Hamp stayed on at the Holborn, but a new manager, J. W. Morrell, took over at Frascati’s. Morrell had ideas of his own, so the canopy finally erected in 1896 may not have been Collcutt’s.

Banqueting Room at the Krasnapolsky Restaurant in 1892 (Historic England Archive)

Instead, Morrell chose to employ C. H. Worley to undertake a series of additions at Frascati’s from 1899 onwards. In particular the restaurant was enlarged with extra rooms and services along the south side of Hanway Street, where Worley supplied a run of two and three-storey fronts in his idiosyncratic style. At ground level the winter garden restaurant was extended on both sides, with the York and Connaught Rooms at first-floor level and new masonic temples a further floor higher. Worley lived only to see the western masonic room built, for he died in 1906, to be succeeded by Reginald Blomfield, who next year designed a small elliptical domed room on the eastern end of the Hanway Street front, and altered the Oxford Street basement. The builders Godson & Sons undertook most of these jobs. The total capacity of Frascati’s at this stage was about 1,500.

Winter Garden at Krasnapolsky’s Restaurant in 1892 (Historic England Archive)

After the First World War the Collcutt firm returned to Frascati’s. Stanley Hamp, one of Thomas Hamp’s sons, had been articled to Collcutt in the late 1890s and became his partner in 1906. After Collcutt’s retirement Hamp updated Frascati’s in an effort at Empire style. The York Room came first (1920–1). Recasting the interiors facing Oxford Street followed in 1927, when Hamp created a spacious new foyer and pepped up the dour brick frontage with gilt metalwork, electric lighting and a glass valance over the entrance. Godson & Sons were once again the builders for this work, with decorative panels by Eleanor Abbey and plaster relief panels by Percy Bentham. Collcutt & Hamp added a small extra building to expand the service accommodation of Frascati’s on the north side of Hanway Street, at No. 18, in 1925.

Frascati’s Restaurant in 1920 (Historic England Archive)

Though the restaurant was re-equipped after the Second World War, once again under Collcutt & Hamp, it closed in 1954. The Land Securities Investment Trust bought the premises and hired Fitzroy Robinson & Hubert H. Bull, architects, to adapt them to a mixture of commercial uses. The conversion took place mainly in 1957. The front building at 26–32 Oxford Street was reclad with a modern front and divided between shops on the ground floor and a language school above. The great domed space behind survived in carcase, concealed from sight. Floored over and shorn of all ornament, its upper level became an open-space banking hall for Lloyd’s Bank in 1983, numbered as 32 Oxford Street. The whole premises, back and front, were finally demolished in 2013, so that no trace of Frascati’s now remains.

References

- Lt.-Col. Newnham-Davis, Dinners and Diners, Where and How to Dine in London, 1899, pp. 220–1

- R. W. Lewin, 2 October 1893, in LMA, LCC/MIN/10811.

14 Responses to “Frascati’s Restaurant, 26–32 Oxford Street”

- 1

-

3

Grand Cafés of Edwardian London – The London Wanderer wrote on 15 July 2020:

[…] Survey of London (2020), Frascati’s Restaurant, 26–32 Oxford Street, available online at //blogs.ucl.ac.uk/survey-of-london/2020/06/26/frascatis-restaurant-26-32-oxford-street […]

-

4

Sam Eedle wrote on 13 August 2020:

I have a large group picture, including my grandfather, taken at Frascati’s, in what looks like a function room, in 1932. He was there with his former comrades,veterans of the Westminster Dragoons who fought in Egypt, Palestine and on the Western Front during the Great War.

-

5

Antony Miller wrote on 5 June 2021:

Good afternoon and thank you for a fascinating article. Inspected of Hanway Street reveals extensive 19th and early 20th century facades featuring generous arched windows and engaged granite pilasters, surely survivals. Furthermore the open ceilings of the current shop, Primark, reveal vestiges of early 20th C construction, in the areas equating to the kitchen and stores and surrounding areas on plan. There are even traces of fibrous plaster mouldings, which I fancifully think may have once resonated to the Frascati orchestra, so perhaps all was not swept away. It’s substantial loss was however tragic.

Kind regards

Antony -

6

Peter Ibsen Christensen wrote on 28 December 2021:

Hello,

I have just read the comments above concerning Restaurant Frascati, London.

My grandfather was employed as waiter there in the 1920 ies, so I have a “folder” with

21 pictures of the rooms in the restaurant.

it says Restaurant Frascati, London, W., Telephones: 316 Gerrard, Telegrams: Frascato London. And contains following pictures:

Vestibule – Winter Garden Crush Room – Winter Garden – Winter Garden Salon – Winter Garden Cafe – Winter Garden Alcove – Grill Room – Balcony Lounge – Balcony – Balcony Salon – Balcony Alcove – Louis XIV Salon – Alpha Salon – York Room – Alexandra Hall – Masonic Room – Masonic Temple – Victoria Hall – Rothesay Ante Room – Rothesay Room – Gordon Room.Kind regards,

Peter

Denmark -

7

Stephen Elsey wrote on 7 January 2022:

Fascinating. Lovely Photos. My Grandfather and Aunt were both employed there in the 1920’s.

-

8

Chris J Coward wrote on 15 June 2022:

My grandfather worked as a waiter at Frascati’s, Trocadero and The Ritz where he was as shown in the Census 1921. Harry Bundock worked at The Holborn Restaurant according to the Census in 1921 and his wife was a witness at my grandfathers wedding in 1918.

In 1914-15 my grandfather had two coffee bars in London, the ‘Rendez-vous Coffee Bar’ at 143a Oxford Street and ‘The Egyptian Café’ at 36 Greek Street, Soho.

Many thanks for the blog and history of Frascati’s in London.

Chris

England -

9

Atilla wrote on 17 December 2022:

I was in the language school (L.T.C.) there during the winter of 1978. Interesting to learn about the building’s fascinating history almost half a century later.

-

10

Atilla wrote on 20 December 2022:

What color was the facade? And why is my earlier comment not published?

-

11

Graham Hoadly wrote on 17 July 2023:

This is a fascinating blog. I wonder if you may be able to help me. I have a photograph of a Masonic Lodge Meeting (Bedford ~Lodge 157) possibly taken around 1901, as the black rosettes on their aprons suggest mourning. The group, in regalia are standing before a very idiosyncratic porchway with curious carved columns in a vaguely Egyptian or Babylonian style. I can’t seem to find a photo of the entrance to Frascati’s at this period – but according to Lane’s Masonic Records website, they state that the Lodge did meet at Frascati’s by 1910. I’m not sure if they did so earlier. I just wonder if you’d be able to confirm or dismiss the possibility that the photograph was taken outside Frascati’s, please. I am happy to send the photo if you could furnish me with an address to do so. Many thanks. Graham

-

12

PJ Hester wrote on 18 September 2023:

Hello,

Frascatis was the favourite restaurant of Selfton Delmer, propagandist for the PWE

(Political Warfare Executive) during WW2. Researching for a novel and fact checking I would love some more information on Frascatis during that time. I understand it was bombed at some stage and cannot find the date. Can anyone help please?

Cheers PJ -

13

Stephen Cox wrote on 11 February 2024:

I can’t be precise about the date but during the war my father, the Chief Estimator at Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company, at Chelmsford, who seemingly needed to visit their head office in the Strand, Marconi House, once brought me with him, and my mother for her annual visit t to Selfridges, and we lunched at Frascatis. But on a second visit, seemingly half the restaurant, to the right, was screened off by ceiling height tarpaulins, having been bombed, it seemed. That was probably1946.

As a ten-year-old. Frascatis stuck in my mind not so much for the tarpaulins but that the waiter made me a cordial of three different colours in separate layers, a detail you don’t forget! -

14

Lisa Watts wrote on 16 June 2024:

My uncle, Howard Carroll, celebrated his 21st birthday at Frascati’s in November 1942. I’ve attached the menu, which looks very impressive for wartime. Howard had an eventful war career as an RAF pilot officer during which he was shot down three times, once over the North Sea, which earned him membership of the ‘Caterpillar Club’, and another time over Belgium after which he was guided to safety in Spain and Gibraltar by members of the French Resistance. Sadly Howard died in late 1945 in an air accident in bad weather delivering aid to Germany.

Close

Close

What a stunning set of photos! I would like to know if the site was recorded before demolition?