Survey of London volume on Oxford Street

By the Survey of London, on 3 April 2020

The Survey of London team is continuing with its work in isolation due to the current public health crisis. While it has been unfortunate but necessary to postpone two major events in our calendar, the launches of the Jewish East End Memory Map and a new volume on Oxford Street, these milestones can still be marked. Other projects in South-West Marylebone and Whitechapel continue to move forward.

Cover of Oxford Street, Volume 53 in the Survey of London’s main series. Published by the Paul Mellon Centre for the Bartlett School of Architecture at University College London (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

We are looking forward to the publication of Oxford Street, the fifty-third volume in the Survey of London’s main or parish series, on 14 April 2020. In the Survey’s 126-year history, Oxford Street is the first volume to focus on the development and architecture of a single street. In recent weeks images of Oxford Street have proliferated in the news, showing closed stores and pavements cleared of the vibrant street life and crowds that usually attract and repel visitors in equal measure – a reflection of these extraordinary times. The volume charts the history of the remarkable and enduring success of Oxford Street as a magnet for shoppers, examining its buildings and transport links as well as its social and cultural life.

Oxford Circus, buskers and Hare Krishna followers at entrance to the tube station, 2016 (© Lucy Millson-Watsons for the Survey of London)

The Survey’s new volume offers insights into the history and growth of shopping in London, along with the reasons for Oxford Street’s unique and enduring success – initially, its advantageous position between Mayfair and Marylebone, and later the fast and convenient transport networks that brought customers to its shops from the suburbs and beyond. Oxford Street is organized in a linear format, covering both sides of the street from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch. Twenty-two chapters cover discrete chunks of Oxford Street between the cross-streets, with an interest in existing buildings and those that have been demolished.

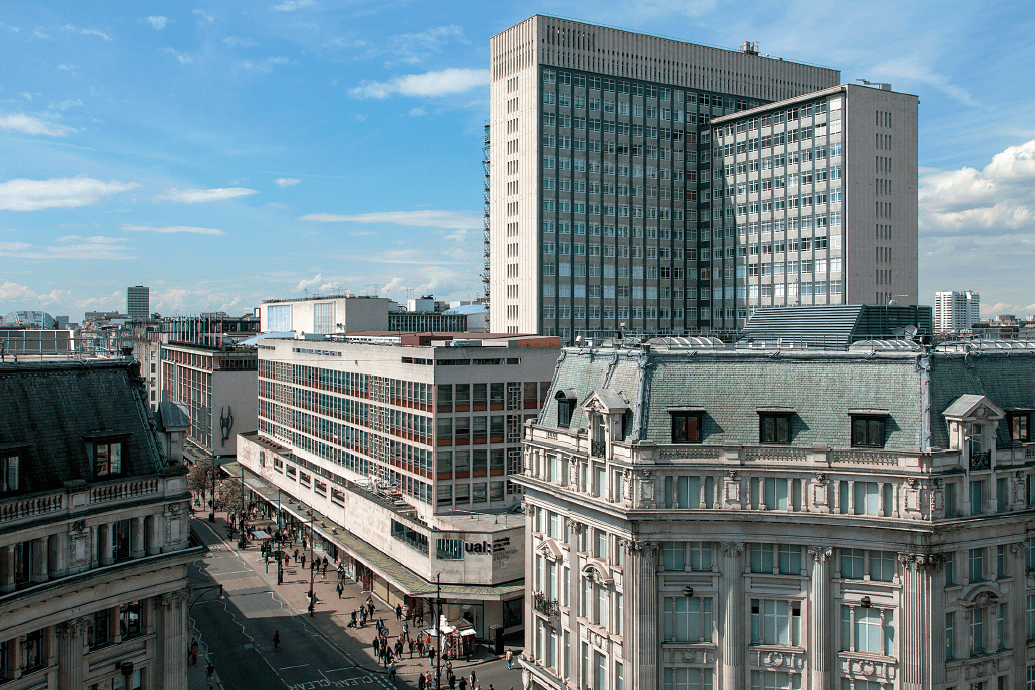

Looking west from Oxford Circus in 2016, with 242–276 Oxford Street and tower block at 33 Cavendish Square in centre, John Lewis beyond (© Lucy Millson-Watkins for the Survey of London)

The Survey’s research on Oxford Street followed on from the publication of two volumes on South-East Marylebone in 2017. That study covered an extensive portion of the West End north of Oxford Street, or the area bounded by Marylebone Road at the north, Cleveland Street and Tottenham Court Road at the east, and Marylebone High Street at the west. A fourth volume, South-West Marylebone, is currently in progress, examining the area immediately west as far as Edgware Road. This research on the West End is balanced by ongoing work towards two volumes on Whitechapel that are expected to be published in 2022.

As one of the longest continuous shopping streets in Europe, stretching for more than a mile in length, Oxford Street has a distinctive topography and character. It has been a major road since the Roman times, when it formed part of an arterial route leading westwards from the City. This highway came to be known as the Tyburn Road, a name derived from a brook (the Tyburn or Ay Brook) that has long since been overrun by urban development. By the time of the Norman Conquest, a hamlet had sprung up near the brook. In 1200 there was a small roadside church on the north side of the highway; its site may be identified today as somewhere between the two arms of Marylebone Lane.

Schematic map of Oxford Street and Edgware Road, c.1500–1700 (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

Tyburn as a place name was eventually replaced by Marylebone, after the dedication of the church following its relocation to a site further north in the fifteenth century. Tyburn carried dreadful associations of the public executions that were carried out on the site of the present junction at Marble Arch from 1196 to the 1780s. The highway served as the last route of condemned prisoners, who were often accompanied by riotous and drunken crowds of onlookers. By the seventeenth century the name Oxford Street was in common use, reflecting the highway’s status as the main route to Oxford. The emergence of the alternative name preceded the beginnings of bourgeois development on the estate of the Cavendish–Harleys from the 1710s, yet its use and adoption conveniently helped to shake off the notoriety associated with the gallows at Tyburn.

Today Oxford Street is better known as a popular centre for shopping, drawing in crowds of tourists and shoppers from the capital and its suburbs. Through the research towards the volume, it has been possible to pinpoint Oxford Street’s transition into a major shopping destination to the 1770s. By this time, the executions at Tyburn had ended and the road was resurfaced with granite blocks. The street lighting was also enhanced by increasing the number of lamps. Shopkeepers were attracted by the opportunity to establish shops on a major road within reach of the upmarket residents of Mayfair and Marylebone. Many entrepreneurs were connected with the drapery trade and set up in small shops based in single houses, often with staff accommodation on the upper floors.

Site plan showing properties purchased for John Nash’s circus of 1816–21 (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

Shopfront of Marks & Co., 395 (old numbering) Oxford Street, design by R. Norman Shaw, 1875 (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

In the nineteenth century the dominance of small shops was challenged by the rise of covered bazaars for small traders, often tucked into former yards or stable areas behind modest street fronts. The bazaar has often been understood as a precursor to the department store, which began to appear in Oxford Street with the rebuilding of Marshall & Snelgrove in the 1870s. Other major department stores of the late nineteenth century included John Lewis and D. H. Evans, which started as small drapery businesses before gradually engulfing entire blocks. These household names were joined by Bourne & Hollingsworth, Waring & Gillow and Selfridges in the Edwardian years. Department stores were furnished with comfortable amenities such as restaurants and rest rooms for customers, while staff were increasingly transferred from ‘over the shop’ accommodation to separate homes. Selfridges in particular represented a new scale of ambition, consumption and glamour among department stores in London and internationally.

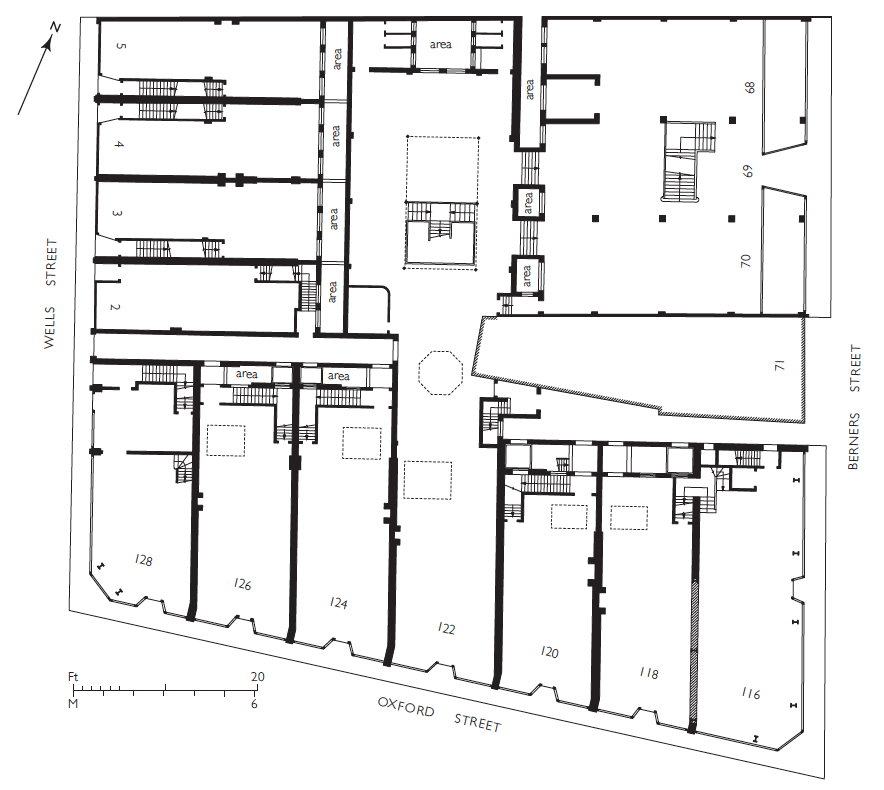

Plan of the ground floor of Bourne & Hollingsworth, c.1905. The store was then in possession of most of the block but had yet to unify the premises, which had been designed in 1898–1901 for separate occupation by smaller shops (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

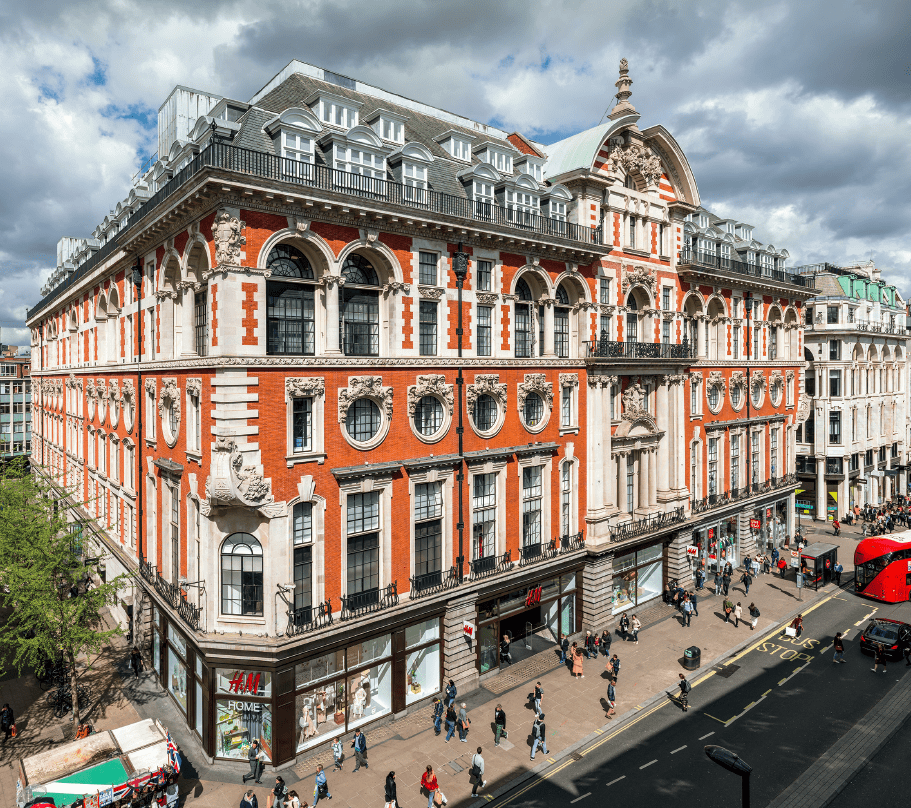

164–182 Oxford Street, former Waring & Gillow store, in 2019. R. Frank Atkinson, architect, 1904–6 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

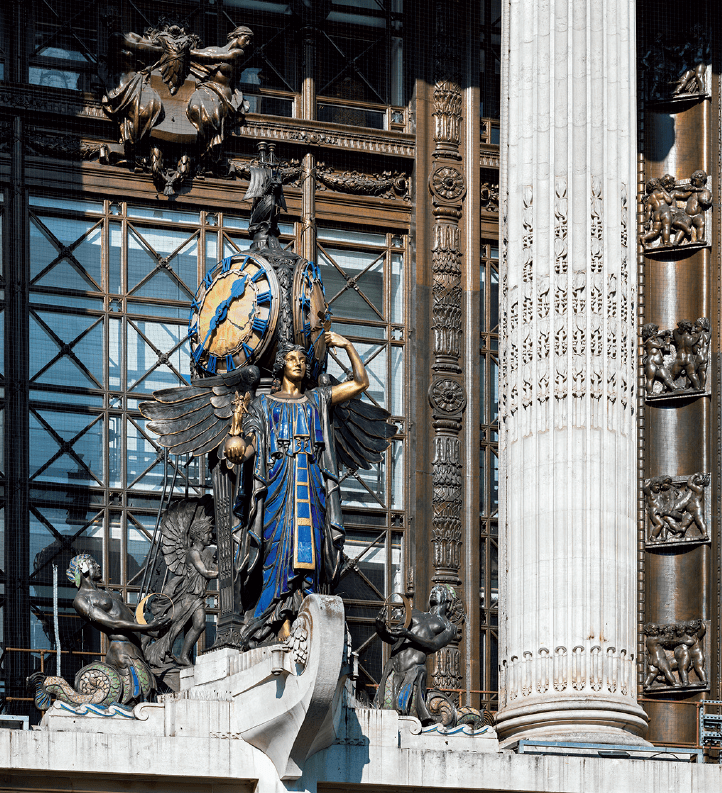

Queen of Time figure above the entrance of Selfridges in 2018. Gilbert Bayes, sculptor, 1931 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Peter Robinson, former restaurant on top floor of Oxford Circus block, now accounting department of Topshop, in 2013, with murals by George Murray (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The arrival of improved transport links in the Edwardian period extended Oxford Street’s appeal to shoppers, securing its status as the capital’s most continuously successful shopping street. Oxford Street was serviced by a range of underground lines connecting to four stations at Tottenham Court Road, Oxford Circus, Bond Street and Marble Arch. The Central Line was opened in 1900, followed by the Bakerloo Line in 1906. In the following year, the Northern Line opened at Tottenham Court Road. In 1969 the Victoria Line opened at the newly remodelled Oxford Circus Station, boasting a new concourse accessed from each quadrant of the circus. With the impending arrival of the Elizabeth Line, connections will be further improved.

Tottenham Court Road Station, vestibule with mosaics by Eduardo Paolozzi in 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

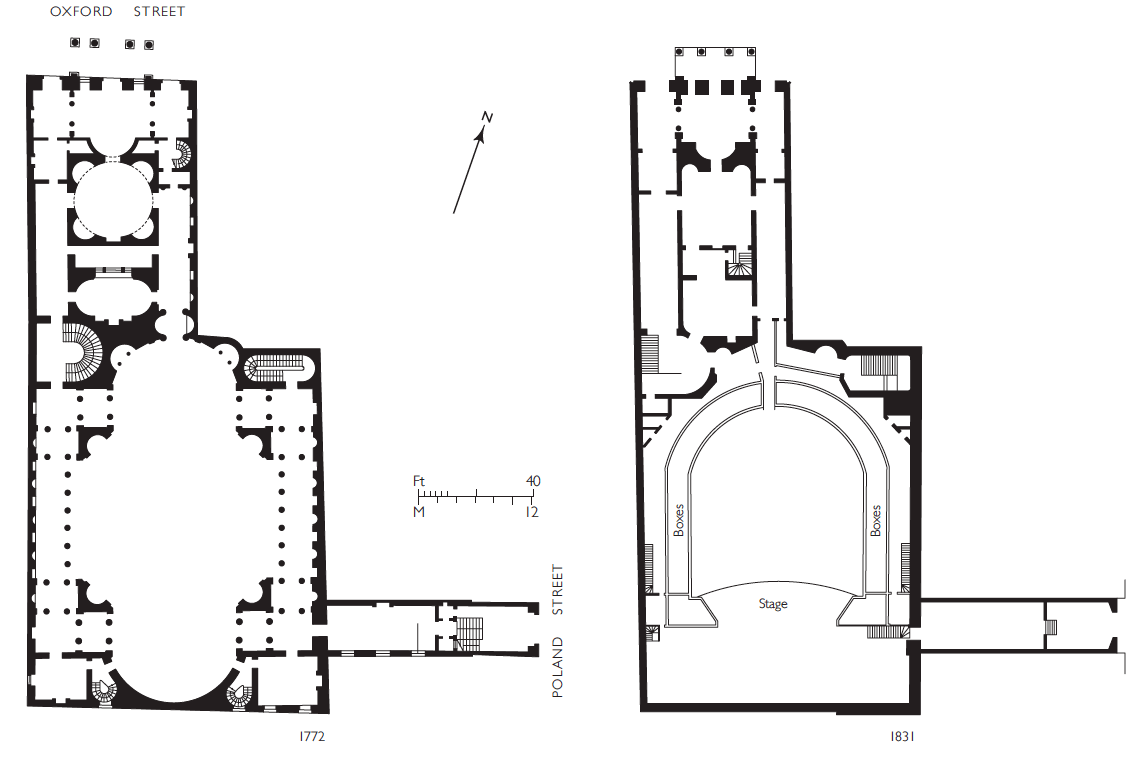

Despite the concentration of shops and stores, Oxford Street has also long been a hub for entertainment, including restaurants, music halls, theatres and cinemas. The celebrated Pantheon, an entertainment venue first built to designs by James Wyatt in 1769–72, is the focus of a chapter that was written by the late Francis Sheppard and first published in Volume 32 on St James Westminster (1963). From the 1890s onwards tearooms and cafés sprung up at street level, led by the J. Lyons chain. Another well-known establishment was Frascati’s Restaurant, which operated in spacious and elaborate premises between 1892 and 1954. An early picture house was established at No. 165 in 1906, followed by Cinema House at No. 225 in 1910, when it was hailed by the Building News ‘the last word in living-picture theatres’. Social and cultural life continued to develop in Oxford Street during the Second World War, with bars, clubs and exhibitions along the street. The future 100 Club was established in 1942 as a venue for live jazz in the basement of 100 Oxford Street, where it continues today. Another remarkable survival is the Flying Horse, the last true pub in Oxford Street. The volume includes an appendix of Oxford Street pubs that conveys the extent of the pubs formerly in the street.

The Pantheon, plans. Left, ground plan as originally designed by James Wyatt, 1769–72. Right, ground plan in 1831 showing N. W. Cundy’s theatre of 1811–12 (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

311–317 (left to right) Oxford Street in 2016. Left, former Woolworth store at No. 311; centre, former Noah’s Ark pub at No. 313; right, part of Nos 315–319 (© Lucy Millson-Watkins for the Survey of London)

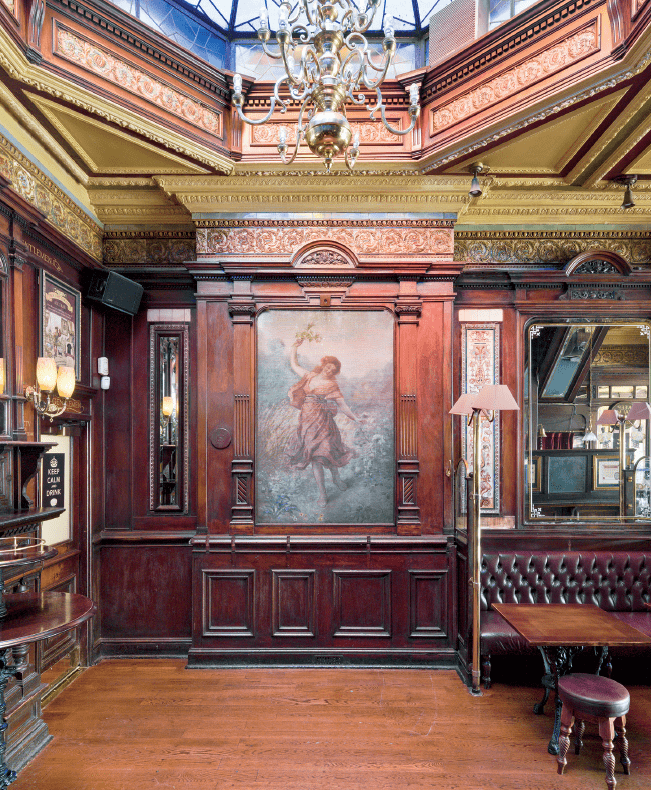

Flying Horse pub, interior detail, showing painting of Spring (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Pavilion Cinema, plan and elevation to Oxford Street, 1913. Frank Verity, architect (© Survey of London, Helen Jones)

The 100 Club in the basement of 100 Oxford Street, 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Oxford Street contains more than 350 illustrations, including drawings and maps by Helen Jones, the Survey’s architectural illustrator, and a variety of historic photographs. New photography has been carried out by Chris Redgrave of Historic England with support from the Portman Estate. The volume also contains photographs of the sights and atmosphere of Oxford Street, recorded by Lucy Millson-Watkins in 2016. The volume has been edited by Andrew Saint and produced in the Survey’s current house style, designed by Catherine Bankhurst under the supervision of Emily Lees at the Paul Mellon Centre. The volume is now available from Yale Books for £75. The draft chapters have been made available online via our website, in advance of a fuller online version in the future.

Park House, 455–497 Oxford Street, looking east from Park Street in 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

7 Responses to “Survey of London volume on Oxford Street”

- 1

-

2

Survey of London wrote on 14 April 2020:

Dear Mr Bulmer,

Thank you for your enquiry. The present street numbering along Oxford Street came into force in 1880, so No. 116 corresponds to the Bourne & Hollingsworth site between Berners Street and Wells Street. In 1902 Bourne & Hollingsworth took the east end of 116–128 Oxford Street, a range built in two phases between 1898 and 1901 as an investment by Salaman & Co., ostrich feather merchants, to designs by the Berners Estate’s surveyor, John Slater. Four shops were thrown into one, with brass-framed windows, green-painted woodwork and sunk lettering in gold. Please see the plan of the site in the article above, showing No. 116 at the corner with Berners Street. The entire block was rebuilt in stages between 1922 and 1958 for Bourne & Hollingsworth.

I hope this helps with your research into your family history.

Yours sincerely, Amy Spencer -

3

Gregory Hubbard wrote on 10 April 2020:

Park House? Real architecture has been demolished for the likes of this behemoth. How ugly must a building be before someone says ‘NO!’

London is becoming little more than a bad copy of the most unattractive parts of New York, much of whose charm was lost long ago. -

4

John wrote on 14 April 2020:

Is there any coverage of the Cumberland Hotel and the large house or houses that existed on the site prior to the construction of the hotel? From about 1911 and during World War I a house there was occupied by Lord Charles Beresford, M.P., and later Baron Beresford.

-

5

Survey of London wrote on 16 April 2020:

Dear John,

Thank you for your interest in the Survey of London’s volume on Oxford Street. The Cumberland Hotel is covered in detail, but the early history of the site is less exhaustive. Please note that the draft chapters for the Oxford Street volume are available via our website. The account of the Cumberland Hotel may be found in Chapter 11 (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/architecture/research/survey-london/current-area-study-oxford-street).

Kind regards,

Amy Spencer

Survey of London -

6

Nick Bailey wrote on 25 May 2020:

Does the Survey include any information on the Berners Estate? Do you know when it was established, what area it covered and when it was sold off? I think Lord Berners gave some land in Mortimer St to the Middlesex Hospital so it must have extended that far north. Many thanks

-

7

Colin Berrett wrote on 31 October 2020:

As a sixteen year old I started my career as a commercial artist with a company called Individual Artists in the building that occupied the corner of Park Street and North Row W1 that was demolished to build Park House. Now in my eighties I am writing my life story for my grand children. I have searched the internet on many occasions but cannot find any photos of this corner in the 1960’s or later. The only ones found are the demolision site for Park House with so much distruction.

Can you help please?

Close

Close

What an interesting publication in prospect. I am researching my grandmothers family history and she is listed as living at 116 Oxford Street in 1916/17.

I am trying to ascertain if that was the Bourne & Hollingworth building at the time?

She was either a live in housekeeper or possibly drapers assistant

Any confirmation or notes on that building gratefully received!