The ‘bijou’ or ‘dwarf’ houses of the Howard de Walden grid. Part 2: the inter-war period

By the Survey of London, on 19 January 2018

A previous blog post (24 November 2017) considered the smaller Victorian and Edwardian mews-corner houses that are such a distinctive feature of the east-west streets of the Howard de Walden Estate in Marylebone. Today we look at three exceptionally fine later examples of the genre, all designed for the Marylebone builders and developers Bovis Ltd by notable architects of the inter-war period – Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, G. Grey Wornum, and Burnet, Tait & Lorne.

22 Weymouth Street – a house by Giles Gilbert Scott

22 Weymouth Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

22 Weymouth Street is one of Marylebone’s jewels – a rare domestic work by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, designed in the early 1930s when he was at the height of his powers and working also on Cambridge University Library and Battersea Power Station.

The house was a speculation for Vincent Gluckstein, chairman of Bovis Ltd, who had been chasing the site since 1928, having recently rebuilt No. 26, a few doors along. Initially, the Howard de Walden Estate suggested two small residences as possible replacements for the double-fronted house that previously stood here. But Gluckstein eventually had his way and devoted the whole plot to just one, larger house, for which Scott was providing plans by 1933, assisted by his younger brother Adrian.

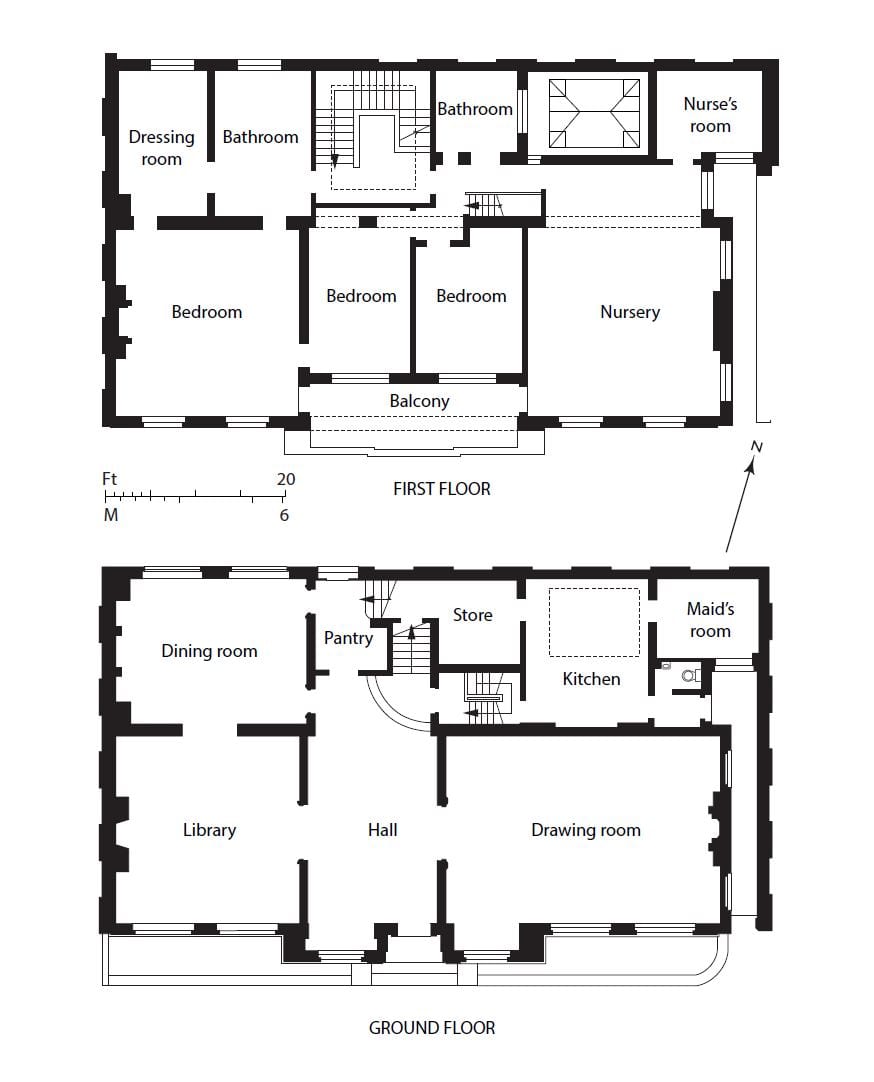

Even so this was still a compact dwelling and as such was carefully planned by the Scotts. There was only a partial basement, occupied by a boiler room. The kitchen, pantry and maid’s room were placed at the rear of the ground floor, which otherwise was given over to a suite of reception rooms: a front library and drawing room either side of a central hall, and a rear dining room. Upstairs were bed and other family rooms, and servants’ accommodation was provided in an attic, lit by rear windows.

In form the house is an updated version of the earlier mews corner houses hereabouts, being of two storeys only, though with a tiled mansard roof for the attic. Scott relied on high-quality brickwork and his immaculate sense of proportion for effect. The elevation has a classic, symmetrical simplicity, dominated by the broad, Georgian-style fenestration, with movement provided by the subtle interplay of rectangular forms – the ground-floor windows either side of the door break forward to make an entrance porch (apparently a late alteration to the design), above which the first-floor central windows are recessed as a sun balcony. The overall effect is very similar to the two-storey brick house that Scott had built for himself a decade earlier in Clarendon Place, Bayswater (known as Chester House). Inside No. 22 the feeling of modernity gave way to a more conventional ambience, with much timber panelling, particularly in the library, and the use throughout of antique carved marble or timber fireplaces.

Scott’s exceptional ability to leaven his unpretentious brand of modern architecture with a strong dose of traditionalism eased relations with the Howard de Walden Estate, as did the fact that he and his brother shared an alma mater (Beaumont College) with their fellow Roman Catholic Colonel Blount, the estate surveyor. Thus he was spared the worst of the wearying interference from Blount that plagued his contemporaries G. Grey Wornum and Francis Lorne over the mews corner houses that they were also designing for Bovis. In the end, however, he lost his patience when Blount, a stickler for uniformity, persisted in criticizing the variegation of the bricks – the identical four-inch type that Scott had specified for Cambridge University Library, then also under construction, where they had been roundly praised. ‘It is quite impossible to obtain any coherent effect unless such questions are under one control’, Scott told Blount candidly.

The house must have been close to completion by the end of 1934 when it featured in the architectural press but no acceptable buyer came forward when offered for sale in 1936. Vincent Gluckstein seems to have been using the property himself at that time. Its next occupant in 1938 was (Sir) Eric William Riches, a surgeon at the Middlesex Hospital. As Riches intended also to practice privately, the drawing room was partitioned for him to create a suite of consulting and examination rooms and secretary’s office. Riches was to remain at No. 22 until 1976, since when the partitions have been removed and the drawing room reinstated. Later residents included the multimillionaire Indian businessman G. K. Chanrai and his family in the 1980s and 90s.

Proposals for radical change to the house in 2009, including the addition of another storey, led to its being listed at the request of the Twentieth Century Society.

39 and 40 Devonshire Street – two houses by Burnet, Tait & Lorne

39 and 40 Devonshire Street form a surprising pair of dwellings. The latter has an idiosyncratic neo-Georgian street front, with prominent window shutters and a steep pyramidal roof punctured at the eaves by dormer windows; whereas its partner, tucked away in the mews, is starkly modern in appearance. They were designed as a pair in the early 1930s for Vincent Gluckstein by Sir John Burnet, Tait & Lorne, with some input from the Howard de Walden estate surveyor, Colonel Blount.

40 Devonshire Street, at the corner with Devonshire Close (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

39 Devonshire Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London, © Historic England)

By 1930 Gluckstein had decided to buy the old premises on this corner site, which included a mews pub, the Cape of Good Hope, intending to demolish all for new residences. Burnet, Tait & Lorne began planning in the summer of 1931 but financial concerns about the effects of the Depression on property obliged Gluckstein to proceed initially with only the mews house at No. 39. The dapper and worldly Francis Lorne, a recent addition to the practice after a lengthy residence in Canada and the USA, was the partner in charge. He, his American brother-in-law Ludovic Gordon Farquhar (who had worked for Raymond Hood) and their international team of assistants designed a relatively plain two-storey brick box with steel-framed windows. Lorne also dealt effectively with Blount’s disquiet and requests for a more traditional type of house (‘we have a reputation to maintain’, Lorne told him), and was able to carry the scheme through without too much alteration – though the incorporation of window shutters is a familiar Blount touch. Even so, perhaps the style was too raw for Marylebone society as the building never saw residential use, being acquired in 1933 by G. Grey Wornum and converted to his architectural offices. Wornum was succeeded in 1950 by Sydney Clough, Son & Partners. Poor modern refenestration has diluted the building’s vigour.

39 Devonshire Street in 1933 (© Historic England Archive)

39 Devonshire Street, interior in 1933, when in the occupation of G. Grey Wornum (© Historic England Archive)

Lorne and Farquhar must have known that such an uncompromising elevation, difficult enough to achieve in a mews, would be unacceptable on a Marylebone street front. At No. 40 the brand of Georgian Revival architecture they contrived is reminiscent of Lutyens’s domestic Queen Anne style of the 1910s. The obtrusive shutters, which detract from the design’s clarity, were not present in their original drawings. The first resident in 1935 was Louis Donn, of a Whitechapel family of tobacco merchants.

39 Weymouth Street – a house by G. Grey Wornum

Beyond the Harley Street Clinic, at the corner of Wimpole Mews, stands 39 Weymouth Street, one of the 1930s rebuildings in the area by Bovis Ltd, in this instance the work of G. Grey Wornum, architect of the new RIBA headquarters on Portland Place. That commission won him renown for spatial dexterity and commitment to high-quality fittings, qualities apparent in this interesting house.

39 Weymouth Street (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England)

Wornum’s involvement is not readily discernible from the rather staid Georgian-style frontage. His original plans of 1934 for Vincent Gluckstein of Bovis were more radical, for a flat-roofed modernistic house, but Colonel Blount, the Howard de Walden surveyor, wanted something more ‘pleasing’ and in harmony with the traditional character of the estate. Forced to concede to Blount’s insistence on a pitched roof, he managed largely to conceal it behind a high parapet, but ignored persistent requests for distracting window shutters to be added to the elevation. The only contemporary touch is the Deco curve of the rear wall in the adjoining mews.

39 Weymouth Street, rear view from mews (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England)

But Wornum’s hand was to the fore inside. Although the house is not listed and has been modernized on several occasions, its interior retains much of the character and some of the features of his original design. The main living space is an exhilarating double-height front room, dominated by an oversized window and giant chimneypiece of pink travertine marble – still with its Wornum-designed firedogs. The room’s original proportions have been restored by the removal of a pair of full-height bookcases either side of the chimneypiece, commissioned from Dennis Lennon in the 1960s. An opening leads to a small dining recess (with its original dumb waiter, concealed in a macassar ebony sideboard), and a curved staircase leads up to a mezzanine in the form of a small wood-panelled study overlooking the main living room. The original finish here was bleached Australian walnut; there were concealed striplights to the fitted bookshelves and a pale leather covering to the balcony handrail (now gone). Two bedrooms on the first floor had built-in wardrobes and the living space was maximized by including a roof garden and also a three-bedroomed staff apartment in the basement alongside a large, rubber-floored kitchen.

39 Weymouth Street, hall and staircase (photographed by Chris Redgrave for the Survey of London © Historic England)

The first resident from 1936 until the 1950s was Thomas Lyddon Gardner, chairman and managing director of the Yardley Perfumery and Cosmetics Company, and it is possible that the house was designed specifically for him through Bovis. Photographs of it newly finished were reproduced in the Architect & Building News in 1936 with furniture by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann much in evidence. Lyddon Gardner was a great admirer of Ruhlmann, commissioning him to design furniture in the 1920s and 30s for Yardley’s showroom in Bond Street and acquiring pieces to decorate his own apartment; Ruhlmann also designed for the Yardley showroom in Paris. Lyddon Gardner was followed at No. 39 by (Sir) David Webster, Director of the Royal Opera, who lived here with his partner, the designer and fashion businessman James Cleveland Belle, until his death in 1971.

Close

Close