GCSA at 50 – some thoughts

By Jon Agar, on 12 November 2014

I enjoyed speaking at the Royal Society/CSaP event last night on fifty years of the post of Government Chief Scientific Adviser. I don’t think I’ve ever been on such a daunting and illustrious panel – mine had Lisa Jardine, Sir Robin Nicholson (GCSA under Thatcher), Sir William Stewart (GCSA under John Major) and Lord Wilson (Richard Wilson, Cabinet Secretary under New Labour). The other panel was equally luminous: Jill Rutter (Institute of Government), Geoff Mulgan (NESTA, and another key New Labour figure), Robert May (ex-GCSA) and Mark Walport (the current GCSA, arriving just in time from a meeting on ebola).

I talked about the history of the GCSA from Solly Zuckerman (appointed 1964) to John Ashworth (who stepped down as Chief Scientist, CPRS in 1981). If you are interested in what I said, I’ve copied my notes below.

It would have been great to have longer time to hear more of the personal experiences of offering scientific advice to power. Nevertheless there were some great anecdotes, sound criticism and useful advice. Stewart, for example, told a story about Major’s encouragement to pitch for more money for science. Wilson made eyebrows rise when he recounted the demise of the chief scientific advisor for energy, Walter Marshall, when he, more or less independently, sold four PWR nuclear reactors to Iran. (I didn’t know this extraordinary episode, but a quick search shows that it appears in a modified form in Benn’s diaries.) Wilson also told us how he had to coach Hermann Bondi to not start drawing equations when he gave politicians advice.

I was also struck by the fact that reminisences can conflict with what we, as historians, know from documentary records. I have a collection of advice offered by Nicholson to Thatcher in the 1980s, recently released at the National Archives, that are quite incendiary and paint a very different picture from the slightly rosy memories that surfaced. It did make me wonder for a moment about the uses of memories as testimony. If you formed your view of the GCSA merely from recollections the picture would be very different from one reconstructed from historical documents. It is a sharp reminder that historical memory is political.

I was also struck by the character of Whitehall’s institutional memory. Sometimes this can be very deep – Walport, for example, said twice that we are still in confict between the vision of Northcote-Trevelyan (the two authors of the report on the civil service that established the generalist-specialist split, see my book The Government Machine for some consequences) and the failed reforms of Fulton (which tried to raise the status of specialists in the civil service). But elsewhere, it was clear that Whitehall can forget what it once knew. Lord Wilson recalled Margaret Thatcher’s astonishing 1988 speech on climate change as if this was the first entry of this issue. But in fact, as I have researched, three 1970s chief scientific advisers had given the issue attention, and by the end of the decade ministers knew.

Finally, as always happens, I had plenty of things to say which were not, because the discussion went in other directions. One of these was Zuckerman’s list (compiled by me from from various sources) of characters of the ideal GCSA. Here they are:

1) Offer up sensible, reasoned, dispassionate advice

2) Be independent of vested interests

3) Keep in touch (in civil service and in science)

4) Answer requests for information. CSAs play this role in departments

5) Anticipate information that will be needed, and therefore commission research if necessary

6) Sometimes (!) manage staff

7) Should not be excluded from key discussions (cf Tizard*)

8) Be personally trusted by Prime Minister

9) Be personally trusted by Cabinet Secretary

(1-7 from Royal Institution address, 1984; 8-9 from Dialogue I)

Also there was much more to say about the specific issues each GCSA encountered, and what their influence in each had been. It would be fun to compare the record of GCSAs against Roger Pielke, Jr.’s four different roles he suggests science advisers can take: pure scientist, issue advocate, science arbiter and honest broker. (James Wilsdon at SPRU might be already doing this as part of his interviews with past GCSAs.)

A good event, but perhaps the historical memories, as we should always do, are best read critically.

As promised, here’s my notes (I had seven minutes):

Between the Cherwell-Tizard period Lisa has talked about and the appointment of Robin Nicholson (on my left) in 1981, there were four men who can be considered Chief Scientific Advisors.

Solly Zuckerman was a South African-born zoologist who had conducted the gory but necessary work of investigating the effects of explosives on bodies as well as operational assessments of bombing during the Second World War. He had already performed specific, sometimes informal, advisory roles to parts of Government, before he was appointed Chief Scientific Advisor to the Ministry of Defence in 1960. From then on, “No one ever more completely stormed every bastion of the British establishment” said Roy Jenkins. Interestingly he insisted on a change of name from ‘Chief Scientist’ (‘inappropriate, he thought, for someone who knew little about “hardware”‘**) to Chief Scientific Advisor. Zuckerman repeatedly stressed the requirement of an adviser to challenge received opinions and intrenched interests. His views could be ‘heterodox’, rejecting battlefield nuclear weapons for example against the view of chiefs of staff. In 1964 Harold Wilson wanted to make Zuckerman a minister of state, leading on disarmament issues. Zuckerman declined. But his role as CSA for MoD was also soon untenable, perhaps because Denis Healey and Zuckerman never quite saw eye to eye. The role of GCSA was therefore created for him. He also, and he never tired of telling people, was made Head of the Scientific Civil Service, a managerial responsibility (albeit an empty title) for 10,000 people – larger than the body of 3,000 administrative civil servants.Zuckerman retired in 1971, but he continued to chip in his views about science and government right up through the 1980s (indeed he retained rooms in the Cabinet Office). His style was to be the trusted consultant, the challenger of received views, and relied on good, wide, informal networking. He was, as Henry Tizard had predicted on hearing of Zuckerman’s appointment, been the ‘courtier’ GCSA.

The technocratic Heath government brought in the era of the Central Policy Review Staff, the “think tank”, assigned the general task of wide and deep critical review. It was also led by a scientist, Victor Rothschild. Therefore it was a moot point whether there should be another GCSA after Zuckerman. The Treasury were against. So was Burke Trend, the Cabinet Secretary, who smoothly said Zuckerman was “sui generis”. Zuckerman insisted. Alan Cottrell, like Zuckerman a defence science adviser, was appointed, albeit as Zuckerman noted at a rank ‘one pip lower than mine’. It was the CPRS – a team of talents – rather than the GCSA that mobilised specialist expertise for the guidance of government.

The down-grading continued with Robert Press, who succeeded Cottrell. Also from the world of defence, appointed unofficial caretaker CSA between 1974 and 1976. In 1981 Zuckerman would write to Robert Armstrong saying Press was ‘really a note-taker … kept on to deal with nuclear weapon matters’, ‘he merely became a mouthpiece of the Aldermaston interests’By now Rothschild’s customer-contractor principle had supposedly framed science’s role in departments, and in consequence more departmental CSAs were in place so that departments could better understand the contracts they would place. The dramatic expansion of the departmental chief scientific advisers had been Cottrell’s suggestion to Rothschild, and he remembers it as a proud moment in his oral history recorded by the British Library (at 50.55)

So in 1975 there was considerable debate about what to do when Press too retired. Was there no need for a GCSA? The Prime Minister – Harold Wilson again – was asked whether he wanted the GCSA replaced, the staff dispersed, replaced with someone even lower in rank. Wilson’s view – and this speaks to the relative insignificance of the GCSA – was that the post could be usefully sacrificed to counter impressions of empire building around the Prime Minister. Indeed the CPRS was enough. Word leaked out. There was a concerted campaign from MPs on the science select committee, Royal Society and Tam Dalyell. Stung, Wilson offered an avowedly cosmetic change. The new man, John Ashworth, could be called Chief Scientist, CPRS.

The authorised biography of Thatcher by Charles Moore records the following first meeting:

Thatcher: Who are you?

Ashworth: I am your chief scientist.

Thatcher: Oh. Do I need one of those?

Ashworth continued until 1981, when he was replaced by Robin Nicholson. But the whole issue of Chief Scientist was caught up in the bloody demise of the CPRS in 1983 at the hands of Margaret Thatcher. Again there was a transition point when everything was up for grabs. The Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology wanted a minister responsible for science and the CS CPRS turned into a GCSA. Thatcher needed persuasion. She herself had rashly declared early on that she, as a scientist, could take care of science policy matters. Now her first preference was to consult a group of adviser, not a single person. Divide and conquer? Or belief that she had the scientific background to make sense of diverse advice? But Nicholson was politically in tune with Thatcher’s values.

Nicholson, as Chief Scientist CPRS now became Chief Scientist, Cabinet Office, a free-standing role that gives us, once an office is built around him, the current GCSA.

* Henry Tizard, a key character in the story of radar and the main science adviser in Attlee’s administration, was excluded from the decision to proceed with Britian’s independent atomic bomb, and, even though he was chair of the Defence Research Policy Committee, excluded from much nuclear discussions thereafter. Attlee’s decision was taken by a secret committtee, and was an extraordinary breach of normal Cabinet decision-making. Tizard’s exclusion had consequences for shaping post-war defence research, as this paper which I co-wrote with Brian Balmer explored.

** Solly Zuckerman, Monkeys, Men and Missiles: an Autobiography, 1946-88, London: Collins, 1988, p. 194.

UK archives of post-war science – notes towards a list

By Jon Agar, on 17 December 2013

I’m working my way fairly systematically through the catalogues of UK archives relating to post-war science, and thought it would be useful to me, and perhaps others, to keep a running list of scientists’ collections. Here’s the list so far, with links via Access to Archives, Janus and other pages. Let me know, via the comments, if you know more …

- Edward ABRAHAM at Oxford, Bodleian (2450 items)

- John Frank ADAMS at Cambridge, Trinity College (1211 files)

- Edgar Douglas ADRIAN at Cambridge, Trinity College

- L. Bruce ARCHER at the Royal College of Art (34 boxes)

- William Thomas ASTBURY at Leeds (378 files)

- Francis Thomas BACON at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (2041 files)

- Ralph Alger BAGNOLD at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (12 boxes)

- John Fleetwood BAKER at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (200 boxes)

- John Randal BAKER at Oxford, Bodleian (110 files)

- Ernest Hubert Francis BALDWIN at UCL (425 files)

- Geoffrey Cecil BARKER at Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College

- Harold BARLOW at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (19 boxes)

- Leslie Fleetwood BATES at Nottingham

- Geoffrey BEALE at Edinburgh (43 boxes)

- Richard Alan BEATTY at Edinburgh (9 boxes)

- Hugh BEAVER at LSE

- George Douglas Hutton BELL at John Innes Centre

- Thomas Brooke BENJAMIN at Oxford Bodleian (275 files)

- John Desmond BERNAL at Cambridge UL (118 boxes)

- Joseph BLACK at University of Bath (4 boxes)

- Carlos Paton BLACKER at Wellcome Library (29 boxes and online)

- Patrick Maynard Stuart BLACKETT at Royal Society (1362 files)

- Geoffrey Emett BLACKMAN at Oxford Bodleian (286 files)

- Jack BLEARS at Manchester MSIM (28 boxes)

- Walter BODMER at Oxford, Bodleian (2216 boxes)

- David BOHM at Birkbeck (10 boxes)

- Hermann BONDI at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (147 boxes)

- Henry Albert BOOT at IEE (124 files)

- Andrew BOOTH at National Archive for the History of Computing, Manchester

- Max BORN at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (84 boxes)

- Keith Frederick BOWDEN at Essex (96 files)

- Vivian BOWDEN at Manchester (293 items)

- Edward George BOWEN at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (11 boxes)

- Lawrence BRAGG at Royal Institution (93 boxes)

- Sydney BRENNER at Cold Spring Harbor and Wellcome Library online

- Mark BRETSCHER at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (11 boxes)

- Jacob BRONOWSKI at Jesus College, Cambridge (in process of cataloguing)

- George Lindor BROWN at the Royal Society

- Frederick BRUNDRETT at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (2 boxes)

- Edward Crisp BULLARD at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (117 boxes)

- Eric Henry Stoneley BURHOP at UCL (49 files)

- George Norman BURKHARDT at Manchester (39 items)

- Joshua Harold BURN at Oxford, History of Neuroscience Library (20 files)

- Roy CAMERON at UCL (12 files)

- James CASSELS at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (5 boxes)

- James CHADWICK at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (73 boxes)

- Ernst Boris CHAIN at Wellcome Library (65 boxes)

- Colin CHERRY at Imperial College (350 files)

- Douglas Richard CHICK at IEE (23 boxes)

- Carol CHURCHER at Wellcome Library (2 boxes)

- Cyril Astley CLARKE at Liverpool (16 boxes)

- Patricia Hannah CLARKE at UCL (9 boxes)

- Robert COCKBURN at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (6 boxes)

- John COCKCROFT at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (124 boxes)

- David Edwin COOMBE at University of Bath (74 boxes)

- Charles Alfred COULSON at Oxford, Bodleian

- Keith Gordon COX at Oxford MNH (500 items)

- Francis CRICK at Wellcome Library (331 boxes and online)

- Frederick Sydney DAINTON at Sheffield (156 boxes)

- Henry Hallett DALE at Royal Society (1077 files)

- Cyril Dean DARLINGTON at Oxford Bodleian (247 boxes)

- Cyril Dean DARLINGTON at John Innes Centre

- John Grant DAVIES (at Jodrell Bank Archive), Manchester

- Peter DAWSON at Manchester MSIM (276 files)

- George DEACON at the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton

- Herbert DINGLE at Imperial College (20 boxes)

- Robert William DITCHBURN at Reading (4 boxes)

- Wilfrid Hogarth DOWDESWELL at Bath (9 boxes)

- Ian DUNHAM at Wellcome Library (17 boxes, 1 oversize box)

- Richard DURBIN at Wellcome Library (34 boxes)

- Eric EASTWOOD at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (66 boxes)

- James Marmaduke EDMONDS at Oxford MNH (400 items)

- Alfred Charles Glyn EGERTON at Royal Society (34 boxes)

- Alfred Charles Glyn EGERTON at Imperial College (12 boxes)

- Charles ELTON at Oxford, Bodleian (276 files)

- George Clifford EVANS at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (5 boxes)

- Ulick Richardson EVANS at Cambridge UL

- Norman FEATHER at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (72 boxes)

- Honor Bridget FELL at Wellcome Library (11 boxes, 3 large boxes and online)

- Malcolm FERGUSON-SMITH at Glasgow and Wellcome Library online

- James FISHER at Natural History Museum

- Harold Walter FLOREY at Royal Society (539 files)

- Edmund Brisco FORD at Oxford Bodleian (38 boxes)

- Peter Howard FOWLER at Bristol (33 boxes)

- Harold Munro FOX at Imperial College (7 boxes)

- Frederick Charles FRANK at Bristol (45 boxes)

- Rosalind FRANKLIN at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (24 boxes) and Wellcome Library online

- Albert FREEDMAN at University of Bath (35 boxes)

- Otto Robert FRISCH at Cambridge, Trinity College (70 boxes)

- Dennis GABOR at Imperial College

- Stanley GILL at Science Museum Library (244 files)

- Harry GODWIN at Cambridge, Clare College (6 boxes)

- Thomas GOLD at the Royal Society (28 boxes)

- Charles Frederick GOODEVE at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (40 boxes)

- Alan William GREENWOOD at Edinburgh (6 boxes)

- Hans GRUNEBERG at Wellcome Library (18 boxes and online)

- John Alan GULLAND at Imperial College

- John Burdon Sanderson HALDANE at UCL and Wellcome Library online

- William Donald Hamilton at the British Library (no electronic record, but handlist available at BL)

- Alister Clavering HARDY at Oxford Bodleian (444 files)

- John Laker HARLEY at Oxford Bodleian

- Geoffrey Wingfield HARRIS at Oxford, Bodleian (24 boxes)

- Douglas HARTREE at Cambridge, Christ’s College (4 boxes)

- Douglas HARTREE at National Archive for the History of Computing, Manchester

- Harold HARTLEY at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (285 boxes)

- William HAWTHORNE at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (241 boxes)

- Humphrey HEWER at Imperial College (198 items)

- Anthony HEWISH at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (9 boxes)

- Harold HEYWOOD at Imperial College (7 boxes)

- Archibald Vivian HILL at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (71 boxes)

- John McGregor HILL at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (15 boxes)

- Robert HILL at Cambridge UL (45 boxes)

- Christopher HINTON at IME Library (93 boxes)

- Christopher HINTON at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (6 boxes)

- Dorothy Mary Crowfoot HODGKIN at Oxford Bodleian (232 boxes)

- Lancelot HOGBEN at Birmingham (82 items)

- Fred HOYLE at Cambridge, St John’s College

- William HUME-ROTHERY at Oxford, Bodleian (11 boxes)

- Kenneth HUTCHISON at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (11 boxes)

- Willis JACKSON at Imperial College

- Bertha JEFFERYS at Cambridge, St John’s College (55 boxes)

- Harold JEFFRYS at Cambridge, St John’s College (69 boxes)

- John Leonard JINKS a Birmingham (68 folders)

- Matthew JONES at Wellcome Library (2 boxes)

- Reginald Victor JONES at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (230 boxes)

- Piotr Leonidovich KAPITZA at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (17 files)

- Bernard Augustus KEEN at UCL (6 files)

- Andrew KELLER at Bristol (2450 items)

- John Cowdery KENDREW at Oxford Bodleian (2000 items)

- John Stodart KENNEDY at Imperial College (41 boxes)

- Peter KENT at Nottingham (94 boxes)

- Aaron KLUG at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (300 boxes) – not open yet

- Hans Adolf KREBS at Sheffield (257 boxes)

- John David LAWSON at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (7 boxes)

- Edmund Ronald LEACH at Cambridge, King’s College (86 boxes)

- John LENNARD-JONES at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre

- Frederick Alexander LINDEMANN at Oxford, Nuffield College (2574 files)

- Edward Hubert LINFOOT at Cambridge UL

- Patrick LINSTEAD at Imperial College

- Otto LOEWI at Royal Society

- Christopher LONGUET-HIGGINS at the Royal Society

- Kathleen LONSDALE at UCL (further papers held privately)

- Bernard LOVELL (Jodrell Bank Archive) at Manchester

- Gordon MANLEY at Cambridge UL (27 boxes)

- Gordon MANLEY at Durham (1 metre)

- Sidnie Milana MANTON at Natural History Museum

- Roy MARKHAM at John Innes Centre

- John MAYNARD SMITH at the British Library (700 files, plus floppy disks)

- Colin William Fraser MCCLARE at King’s College

- James Dwyer MCGEE at Imperial College (55 files)

- William Stuart MCKERROW at Oxford, Natural History Museum (500 items)

- Anne MCLAREN at British Library (152 items)

- Peter MEDAWAR at Wellcome Library (47 boxes and online)

- Helen MEGAW at Cambridge, Girton College (33 boxes)

- Lise MEITNER at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (91 boxes)

- Kurt Alfred Georg MENDELSSOHN at Oxford, Bodleian (28 boxes)

- Alec MERRISON at Bristol (38 boxes)

- Donald MICHIE at British Library (948 files)

- Edward Arthur MILNE at Oxford Bodleian (11 boxes)

- Cesar MILSTEIN at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (1050 items)

- Joseph Stanley MITCHELL at Cambridge UL (146 boxes)

- Peter Dennis MITCHELL at Cambridge UL (2900 items)

- Philip Burton MOON at Birmingham (8 boxes)

- Arthur Ernest MOURANT at Wellcome Library (48 boxes and online)

- Nevill Francis MOTT at Cambridge UL (230 items)

- Dorothy Mary Moyle NEEDHAM at Cambridge, Girton College (153 files)

- Joseph NEEDHAM at Cambridge UL (3400 items)

- Joseph NEEDHAM at Imperial War Museum (150 items)

- Max NEWMAN at Cambridge, St John’s College (5 boxes)

- Peter NIBLETT at Manchester MSIM (6 boxes)

- Ronald George Weyford NORRISH at Cambridge UL

- Henry Proctor PALMER (at Jodrell Bank Archive), Manchester

- Carl Frederick Abel PANTIN at Cambridge, Trinity College (15 files)

- Robert PEERS at Nottingham (7 boxes)

- Rudolf Ernst PEIERLS at Oxford, Bodleian (544 files)

- Lionel PENROSE at UCL (96 boxes) and the Wellcome Library online

- Max PERUTZ at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (45 boxes)

- Rudolf Albert PETERS at Oxfird, Bodleian (11 boxes)

- David Chilton PHILLIPS at Oxford Bodleian (288 boxes)

- Alfred John PIPPARD at Imperial College (7 boxes)

- Guido PONTECORVO at Glasgow and Wellcome Library online

- George PORTER at Royal Institution (121 boxes)

- John Guy PORTER at Royal Greenwich Observatory archive (3 boxes)

- Rodney Robert PORTER at Oxford, Bodleian

- Cecil Frank POWELL at Bristol

- Joseph PRESTON at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (8 boxes plus a roll)

- John William Sutton PRINGLE at Oxford, Bodleian (90 boxes), supplementary collection here (32 items)

- Dietrich PRINZ at National Archive for the History of Computing, Manchester

- Robert RACE at Wellcome Library and online

- Richard RADO at Reading (59 boxes)

- Jack RATCLIFFE at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (32 boxes)

- John RANDALL at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (19 boxes)

- Roderick REDMAN at Royal Greenwich Observatory archive (22 boxes)

- James RENWICK at Glasgow and Wellcome Library online

- Rex RICHARDS at Oxford Bodleian (69 boxes)

- Eric Keihtley RIDEAL at Royal Institution (2 boxes)

- Robert ROBINSON at Royal Society (580 items)

- Joseph ROTBLAT at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (292 boxes)

- Leonard ROTHERHAM at Bath (19 boxes)

- Francis John Worsley ROUGHTON at Cambridge UL (250 items)

- Albert Percival ROWE at Imperial War Museum

- James Henderson SANG at Edinburgh (4 files)

- Fred SANGER at Wellcome Library (10 boxes and online)

- Ruth SANGER at Wellcome Library and online

- Peter Markham SCOTT at Cambridge UL (7800 items)

- George William SERIES at Reading (12 boxes)

- Robert Beresford Seymour SEWELL at Natural History Museum (9 boxes)

- George Lennox Sharman SHACKLE at Cambridge UL (28 boxes)

- Oswald John SILBERRAD at Science Museum Library (5300 items)

- Conrad SLATER (at Jodrell Bank Archive), Manchester

- Francis Graham SMITH (at Jodrell Bank Archive), Manchester

- Frank SMITH at Imperial College (6 items)

- Kenneth Manley SMITH at Oxford, Institute of Virology (151 files)

- Frank SMITHIES at Cambridge, St John’s College (34 boxes, 8 albums)

- Frederick SODDY at Oxford, Bodleian (258 items)

- Harold SPENCER JONES at Royal Greenwich Observatory archives (3.5 cubic metres)

- Maurice STACEY at Birmingham (149 items)

- Walter STILES at Birmingham (78 files)

- Edmund Clifton STONER at Leeds (28 boxes)

- Christopher STRACHEY at Oxford Bodleian (55 boxes)

- John SULSTON at Wellcome Library (139 boxes, 2 outsize boxes, 19 outsize folders)

- Gordon Brims Black McIvor SUTHERLAND at Cambridge UL (29 boxes)

- John SUTTON at Imperial College (13 boxes)

- Richard Laurence Millington SYNGE at Cambridge, Trinity College Library (1700 items)

- Geoffrey Ingram TAYLOR at Cambridge, Trinity College (14 boxes)

- Nikolaas TINBERGEN at Oxford Bodleian (181 items)

- D’Arcy Wentworth THOMPSON at St Andrews (225 boxes)

- Harold Warris THOMPSON at Royal Society (40 feet)

- Michael Warwick THOMPSON at Birmingham (12 boxes)

- George Paget THOMSON at Cambridge, Trinity College (60 boxes)

- Alexander TODD at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (245 boxes)

- Samuel TOLANSKY at UCL (22 boxes)

- Alan Mathison TURING at Cambridge, King’s College (6 boxes)

- Alan Mathison TURING at National Archive for the History of Computing, Manchester

- Alfred Rene Jean Paul UBBELOHDE at Imperial College (37 files)

- Conrad Hal WADDINGTON at Edinburgh (57 boxes)

- Lawrence Rickard WAGER at Oxford, Natural History Museum (1200 items)

- Francis Martin Rouse WALSHE at UCL (5 boxes)

- Ernest WALTON at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (3 boxes)

- Claude Wilson WARDLAW at Manchester (105 items)

- Frederick Edward WARNER at Essex (2500 items)

- David Meredith Seares WATSON at UCL

- James WATSON at Cold Spring Harbor and Wellcome Library online

- Torkel WEIS-FOGH at Cambridge UL

- Maurice WILKES at Cambridge, St. John’s Library

- Maurice WILKINS at King’s College London (170 boxes) and Wellcome Library online

- Denys WILKINSON at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (9 boxes)

- Frederic C. WILLIAMS (at National Archive for the History of Computing), Manchester

- Ian WILMUT at Edinburgh (c. 70 boxes)

- Richard WHIDDINGTON at Leeds (48 files)

- Harold WOOLHOUSE at John Innes Centre

- Gerard WYATT at Wellcome Library (2 boxes and online)

- Charles Maurice YONGE at Natural History Museum (44 boxes)

- Christopher Alwyne Jack YOUNG at Science Museum Library (22 boxes)

- John Zachary YOUNG at UCL (66 boxes catalogued, more info here)

- Solly ZUCKERMAN at University of East Anglia

Plus a few corporate or group archives:

- Anglo-Australian Telescope project papers at Royal Greenwich Observatory archives

- Association of Teachers of Domestic Science at Warwick Modern Records Centre

- Eugenics Society at Wellcome Library (158 boxes and online)

- Ferranti Collection at Manchester MSIM (700 boxes)

- Ferranti family papers at Manchester MSIM (148 files)

- History of Fusion at Cambridge, Churchill Archives Centre (5 boxes)

- Institute of Animal Genetics at Edinburgh (4 boxes)

- John Innes Centre

- King’s College Biochemistry Department at King’s College Liddell Hart Centre

- Medical Research Council Blood Group Unit at Wellcome Library (65 boxes and online)

- Metropolitan Vickers at Manchester MSIM (32 files)

- National Institute of Agricultural Botany Historical Archive

- Nuffield Foundation Science Teaching Project at King’s College London (591 boxes)

- Oxford Enzyme Group at Oxford Bodleian (21 boxes)

- Plant Breeding Institute at John Innes Centre

- Roslin Institute and predecessor institutions at Edinburgh (c.900 boxes)

- Royal Agricultural College at RAC

- Royal Society collections

- Schools Council Integrated Science Project at King’s College London (56 boxes)

- Strangeways Research Laboratory at the Wellcome Library (31 boxes)

- Voices of Science, by the Oral History of British Science project at British Library

The list was mostly generated by using a keyword ‘science’ and restricting the search to 1945-2012, and then going through the 24,480 results. That might sound a lot, but I know for a fact that it misses some collections! After seeking suggestions, I have also trawled the Churchill Archives Centre for scientists, and used National Register of Archives.

I intend to keep this list updated.

Thanks to the following for suggestions: John Forrester, Peter Collins, Stephen Boyd Davis, Richard Noakes, Christoph Laucht, Mauro Capocci, John Faithfull, Simon Chaplin, Jean-Baptiste Gouyon, Chris, Dmitry Myelnikov, Dominic Berry, Alex Hall, Nancy Anderson, Clare Button, Joanna Corden, Jacob Hamblin, Tim Powell, and Jenny Shaw.

The rarest important books of the twentieth century?

By Jon Agar, on 27 November 2013

In 1966, two books were published that have a claim to being the rarest important books (in their original form) of the twentieth century. Ironically, their subject was rarity itself.

In 1966, two books were published that have a claim to being the rarest important books (in their original form) of the twentieth century. Ironically, their subject was rarity itself.

Red Data Book, Volume 1: Mammalia and Volume 2: Aves were the brainchild of the wildfowl conservationist Sir Peter Scott. They were published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). Scott was the chair of the IUCN’s Survival Service Commission. They are loose-leaf binders. Each sheet summarised the facts known about threatened or endangered species and subspecies. They are poignant and compelling compilations, aiming at comprehensiveness, of the next victims of the global, modern wave of extinction.

The reason why they are incredibly rare – in their original form – is that the books’ own readers were given instructions to destroy them, in part. To keep the books up-to-date, new sheets were posted every six month after publication. ‘To avoid confusion’, recommended the book’s introduction, ‘it will generally be found advisable to destroy original sheets removed from the volume when replacements are received’. This advice means that it is quite possible that no 1966 Red Book, in the form it was published in, has survived. Even the British Library’s copies have been updated. The first Red Data Books could be extinct.

The Red Data Books were extraordinarily influential. To say that a creature was a ‘Red Data’ species became a shorthand for rarity and the need for conservation. The template was copied. Volumes on plants, fish and invertebrates followed, as did national analogues. You can now find red data books of the lichens of Britain, the organisms of Malta, or the threatened birds of the United States.

The books were also read in surprising ways. For a listing of standardised data and references, the response of readers could be unexpectedly emotional. Here, for example, is the primatologist Russell Mittermeier, recalling his first encounter:

I still have fond memories of receiving in the mail my copy of the first Red Data Book… I was about 20 when I first received this publication, and it had a profound impact on me. I pored over every page, reading each one dozens of times, feeling awful about those species that were severely endangered, and resolving to dedicate my career to doing something on their behalf (quotation from 2000 IUCN Red List, p. xi).

The reason I am reading the Red Data Books is because I am tracing how science was used to redefine categories of threat to species in the twentieth century. The redefinition of the criteria for inclusion, basing them on quantitative population biology, is a later story, and is the main focus of my historical investigation. (Do get in touch – jonathan.agar@ucl.ac.uk – if this sounds interesting to you.) Nevertheless, the Red Data Books of 1966 are the key texts of this project to assess and categorise the threatened wildlife of the world.

This is what a sheet from a Red Data Book – for Cuvier’s hutia – looked like (plus a pic I found on the web):

Cuvier’s hutia (Plagiodontia aedium) is a medium-sized rodent that is spotted once in a blue moon in the forests of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. As the sheet notes, the creature was not recorded between Cuvier’s description of the type specimen in the 1830s and its rediscovery in 1947. The sheet describes some characteristics, a few scattered distribution facts, and possible reasons for decline (assuming it was ever common). It is a standardised template, deliberately so: gaps were left in plain view to encourage others to fill them with data. The Cuvier’s hutia sheet is white, which means that it was relatively unusual in its scarcity. The Red Data Books were colourful texts: ‘Pink sheets are used to draw attention to those mammals which are believed to be the most gravely endangered. Green sheets are used for mammals whose survival was at one time in question but which are now regarded as out of danger’. There almost no green sheets.

I’m interested in classification, and the criteria used to pigeonhole species. (There are fifteen pigeons and doves pigeonholed in volume 2.) If you look at the Cuvier’s hutia page, down at the bottom left, there is a ‘status category’ made up of letters and numbers. The key for decoding these is as follows. There’s a Category number, (a) or (b) to denote species or subspecies, sometimes some qualifying letters, and, for the rarest, stars:

Category 1. ENDANGERED. In immediate danger of extinction: continued

survival unlikely without the implementation of special protective measures

Category 2. RARE. Not under immediate threat of extinction, but occurring in

such small numbers and/or in such a restricted or specialised habitat that it

could quickly disappear. Requires careful watching

Category 3 DEPLETED…

Category 4 INDETERMINATE. Apparently in danger, but insufficient data

currently available on which to base a reliable assessment of status. Needs

further studyStar listing: *** Critically endangered

Symbols:

(a) Full species

(b) Subspecies

E Exotic, introduced or captive populations believed more numerous than

indigenous stock

M Under active management in a national park or other reserve

P Legally protected, at least in some part of its range

R Included because of restricted range

S Secrecy still desirable

T Subject to substantial export trade

Cuvier’s hutia is a 4(a), a frank – and frequently found – statement of lack of knowledge. The weird lemur, the Aye Aye was a 1(a)***, the Orang utan 2(a)**, and the Asiatic lion, 1(b)*P. The thylacine, almost certainly already extinct, was a 1(a)***P. A similar system was used for birds, so the Maui nukupuu, for example, was a 1(b)P***, and the enormous Monkey-eating eagle of the Philippines was a 1(a)PS***. These symbols are rather important, since the difference of a single letter might mean serious conservation effort or regretful neglect. The assessment was by expert judgement, either by the compilers (Noel Simon in the case of Mammalia and Jack Vincent for Aves) or by specialists of locality and taxon.

In a world of conservation success, the Red Data Books would be empty, every form having been discarded and the books entirely destroyed. In fact, the IUCN’s Red List is now an enormous online resource, which monitors over 70,000 species and lists over 20,000 of them as threatened. The IUCN’s criteria are one of the central organising standards of international conservation, and are even used, in their version 3.1 form, to categorise rare species on their Wikipedia pages (look under the picture, on the top right hand side, for example here).

It is this significance that invites historians’ attention. Why did they take the form they did? Why was the template so successful? Can we trace how they were read and used? What was the place and roles of science in shaping conservation knowledge and practice?

What’s your CHOICE?

By Jon Agar, on 26 November 2013

Material culture is crucial to understanding the history of science and technology, right?

It’s a lesson I’ve taught in many places over the years. One class project that I’ve enjoyed running with students from Manchester, Oxford, Harvard and here at UCL has been to ask them to come up with designs for an exhibition on modern science and technology.

I give them the dimensions of space and an unlimited budget (it is a fantasy, I know). They propose 10 objects, a design and rationale for both. They have always responded with imagination and flair. We discuss the assumptions made, the stories that are possible (and impossible) to tell, how visitors might respond, and what messages about science and technology’s past are most important. It’s a great class.

However, I’ve begun to notice a recurrent feature. Most of the stories that we want to tell are those that are sourced, first and foremost, from written history – history that is built from engagement with primary documents and secondary literature. This, I feel, shouldn’t be the case if material culture is a key to interpreting the major themes of past science and technology. There’s a danger of paying pious lip-service to the notion of the importance of material culture unless we can point to examples of where it matters.

So let me ask a question: what’s your CHOICE?

CHOICE stands for Crucial Historiographical Object in Collections or Exhibitions. I propose that a CHOICE has two ideal features:

1) a CHOICE object reveals significant, otherwise inaccessible, knowledge about a significant historical narrative.

2) materially, either in total or in part, a CHOICE represents a ‘fork in the road’, a moment of significant historical contingency, revealing how history could have been different.

Let me pick out a few words from these features and explain my thinking. Let’s start with ‘inaccessible’. I tend to come to interpreting objects *after* having read about their history. What I rarely – ever? – see is an object that reveals otherwise inaccessible knowledge. Believe me, I’m aware of the tacit knowledge debate, and that is, of course, a kind of relevant, otherwise inaccessible knowledge. But where are the examples of how otherwise inaccessible knowledge contributes to the large-scale historiographical narratives? When have they done so in the absence of written interpretations of the objects?

The key word – I’ve used it three times – is ‘significant’. I would very much like to show an object to students and be able to say: ‘See that? Because we can see that thing we must think of history differently’.

As a naive historian of science, CHOICEs are what I would want to find in a science museum or object collection. Not the only things for sure, but there – and emphasised – nonetheless.

It might be a question that is most relevant to thinking about modern collections. Modern science and technology has generated an immense documentary (as in textual) record that is, in practice if not in preaching, historians’ first and sometimes only port of call. For earlier history fewer documents survive and objects necessarily become our traces of evidence of the past. For most of human existence – prehistory – objects are the only sources we have. If you are studying Magdalenian culture, everything is a CHOICE.

One candidate might be the Science Museum’s rebuilt Difference Engine, of Charles Babbage fame. Only by rebuilding the object with tools and practices matching Victorian ones could it be shown that the scheme was feasible. Of course, we are only prompted to ask the question of feasibility because we know from written documents about the struggle to engineer such a device. Nevertheless, it might pass the tests of historiographical significance, inaccessibility of knowledge and contingency. On the other hand, it is not (if we are worried about authenticity, which we might not be) an ‘original’ object, and I’d like other examples.

So, curators! historians of science and technology! Tell me your CHOICE!

Either CHOICEs exist, in which case we have examples. Or CHOICES do not, in which case what is wrong with my historiographical expectations of scientific or technological objects? Either way, it should be interesting…

GMOs as chimaeric archives

By Jon Agar, on 22 November 2013

I was reading an otherwise very dry and sober account of different definitions of rarity of organisms, written in 1984, and was struck by this odd aside:

Indeed a time can be foreseen when genetic engineering will allow huge numbers of valuable genes to be stored as part of a composite living organism, an animal with multiple features from many species or a vast polyploid plant bearing a hundred different flowers and fruits from its branches.1

The bizarre idea seems to be that in a world of disappearing species, genetic diversity could be archived by combining them in the body of a single organism.

It’s a fantasy of a universal genetic chimaera. It brings up pictures to mind of a monster with the claws of a Siberian tiger, the strength of a mountain gorilla and the carapace of a sea turtle. An animal or plant Frankenstein made to blunt extinction. An Ark made flesh. An Ark of living wood.

I was wondering whether anyone knew of similar or related concepts? Perhaps in science, but maybe more likely from science fiction? It would be fascinating to know whether this suggestion was a single flash of the imagination or whether it has counterparts, a history or a context. If this rings any bells, then please leave a comment below.

==

1. Paul Munton, ‘Concepts of threat to the survival of species used in Red Data Books and similar compilations’, in Richard and Maisie Fitter (eds.), The Road to Extinction: Problems of Categorizing the Status of Taxa Threatened with Extinction, Gland: IUCN, 1987, pp. 71-88, pp. 87-88.

On holiday with Martin Heidegger

By Jon Agar, on 10 September 2013

Half way through my family holiday in the Black Forest I found out that Martin Heidegger had lived in the neighbouring valley. I had accidentally chosen a location only about a mile, as a raven flies, from the little hut in which the philosopher had composed Being and Time. (I say “accidentally”. A few years ago, while driving around the suburbs of Boston, I also “accidentally” found myself taking my family past Thoreau’s pond at Walden. Of course we had to stop and have a poke around. There might be something subconsciously going on with me concerning philosophers and tiny buildings.)

Heidegger had studied at the University of Freiburg. The city lies at the western edge of the southern Black Forest, a few miles from the Rhine and the French border. After the First World War, Heidegger worked as an assistant to Edmund Husserl, the phenomenologist, whom Hannah Arendt would later accuse Heidegger, her lover and National Socialist party member, of murdering. That’s all in the future.

In 1917 Heidegger married, and Elfride’s dowry was spent on a plot of land in the hills around the ski resort town of Todtnauberg. The couple, with a young family, occupied the hut in August 1922. So began a period of great intellectual productivity. Heidegger took up a professorship at Marburg in 1923 and returned to Freiburg, on Husserl’s retirement, in 1927. Apart from a brief post-war absence, for denazification, Freiburg was Heidegger’s institutional house. But his home was in the Black Forest hills. Throughout, while on campus he lectured and supervised a stellar array of students, including Arendt, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Leo Strauss and Herbert Marcuse, Heidegger would return to his hut to live and think.

Martin Heidegger dressed for the part. When he left the city behind, with its university, cathedral and offices, the philosopher would don rustic clothes. Here’s a picture, where we can see Heidegger dressing down, comfortable playing the role of honest, simple farmer. When he left Todtnauberg to commute to work he put back the professorial garb.

Todtnauberg attracts skiers in the winter and hikers in the summer. The town is proud of its humble philosopher-celebrity and has thoughtfully mapped out a guided walk, the “Martin Heidegger Panorama-Rundweg”, which takes you around the surrounding countryside and past Heidegger’s hut. There’s a pamphlet that can be picked from the tourist office, with text in English and German. Oddly, along the Rundweg, there are a series of enormous chairs, artworks that make for uncomfortable sitting. But mostly the impression is, as the pamphlet title suggests, panoramic: a picturesque vista of hills capped with beech and conifers. Halfway along a small farm road dives to the right, and there is Heidegger’s humble abode.

The picture does not really give you the sense of just how small the hut is. It is one storey and the roof would end below my eye level if I stood against the wall. Heidegger might have moved in for the peace and quiet but I can’t imagine family life being quite so tranquil. Perhaps the children were told to play outside. The building is private property – indeed it apparently belongs to the descendants – and a discreet notice on the final path warns us that getting any closer is verboten.

A gentle wisp of smoke tells us that there’s a wood-burning stove inside, but otherwise, for most of its history, Martin Heidegger kept domestic technology to a minimum. The tourist pamphlet is rather charmingly revealing on this point:

From the hut’s simple outer appearance can be drawn conclusions to the inner appearance: the spare furnishing is still unchanged. The most modern thing in the hut is a little radio which bought Heidegger in 1962 for listening the news about the Cuba-Crisis. They got spring water from a near well. During the first years they got no electricity. In 1931 they got an electric connection.

Apparently when Martin received an offer to go to Berlin, Elfride took the opportunity to bargain with the Baden government that, in return, her hut should be connected to an electricity supply. Martin, one presumes reluctantly, accepted the modernisation, even though he stayed in post in Freiburg.

Now, of course, from an STS point of view, this attitude to technology is perhaps the most interesting aspect of seeing how Heidegger lived. When Heidegger was allowed to teach again after the Second World War, one of his first and most famous lectures concerned “The question of technology”. It is one of the foundational texts of the philosophy of technology, and requires some effort to follow. A conservative, Heidegger held a view, shared by many, that the human relationship to the environment had been impoverished by industrialisation. The lecture expressed intense disgust, for example, with the canalisation of the wild Rhine, and lingered over pre-industrial authentic, artisanal worked objects. Heidegger’s profound point was to go beyond merely the observation that we treat our environment in increasingly instrumental terms – as means to ends – and argue that we should wonder why nature has this uncanny affordance to us at all. Nature, he says, has been framed so as to offer us means, and there are other ways we can, and should, relate and live.

On the surface this argument seems to reflect, naturally, the philosopher’s chosen lifestyle: the simple abode, the rustic friendships, and the late admission of modern technologies – electricity for the wife, and a radio only at a moment of a threat of global apocalypse.

We might simply enjoy the mild irony of the Martin Heidegger Panorama Rundweg, a life arrayed in guided country walks, or even note the marked Schwarzwald enthusiasm for electric fences – these are time savers for today’s landowners who manage ski runs in the winter but want quick and effective containment of livestock in the summer. Indeed an electric fence now runs meters from Heidegger’s hut:

However, if you dig a little deeper, you can find out that the sweeping agrarian countryside, with the clear views of the alps in the distance and the cows grazing in the meadows, is not all the land contains. While browsing the small museum in the neighbouring town of Wieden, in the Rathaus across from the tourist leaflets and propped up on display case, was this map of the area:

The map shows the land underneath Heidegger’s feet. There are mine shafts in all directions. Extraction of ores made this part of the southern Black Forest a highly industrial area. Means to many ends. While the philosopher, dressed as a farmer, sat outside his humble hut admiring the view, thinking his thoughts, below men and machines worked hard together.

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Science and Political Integration in Europe

By ucrhmrr, on 2 August 2013

John Krige (1997) has alerted us to the contribution of scientists and not governments in re-organising where and how science is done, particularly in the organisation of transnational scientific cooperation. When viewed from this perspective, new and unexplored histories of science and politics are written. Since the Second World War, the most active geo-political region of scientific cooperation has been Europe, and this cooperation forms a significant part of what we call European integration. Yet what we know about European integration is dominated by political histories which privilege conventional ‘political’ integration commonly thought of as Member States ceding sovereignty to the European Community. Such histories according to Neil Rollings (2007) focus on top political figures and civil servants as the decisive actors. What is surprising is that when we look at European scientific cooperation this often precedes and draws after it conventional ‘political’ integration. From this perspective, scientific cooperation can be seen as a politically creative and binding force. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control is a good example of precisely this.

Based in Stockholm, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), an agency of the European Union officially began life in May 2005. The only serious history yet to be written about the ECDC, as far as I am aware, is by Scott Greer whose account of the ECDC’s origin follows the approach taken by many ‘politician-centric’ histories. Greer tells us that if we want to know why the ECDC came into being, we will have to know more about the activities of a top civil servant Fernand Sauer, and a former European Union Commissioner of public health David Byrne. This is misleading. The ECDC’s mission and organisational structure is based on the planning and lobbying of European epidemiologists and microbiologists during the 1990s who developed, often in competition with one another, what they thought would be more effective ways to control and prevent disease.

In 1992, two epidemiologists Chris Bartlett and Gijs Elzinga proposed to the European Commission that it would be beneficial to identify gaps and duplications in all of the international surveillance and training collaborations that were then currently taking place in the European Union. Following the conclusion that there were gaps (for example in food-borne diseases) and duplications, Bartlett and Elzinga asked for funding from the European Commission for twice-a-year meetings and for a small technical support unit so epidemiologists from participating Member States could strategically develop the surveillance and research of communicable diseases. The Commission agreed to fund this, and what was known as the ‘Charter Group’ emerged at the beginning of 1994 bringing together heads of communicable disease centres from around the EU on a voluntary basis.

Under the Charter Group, a network of disease-specific programmes were developed which used existing national centres like the Réseau National de Santé Publique in France to serve as focal points for the European surveillance of specific diseases such as AIDS and Salmonella infection. This approach to controlling disease became known as the Network Approach. The Charter Group established European data-sets, identified emerging diseases, and assisted in the response to national outbreaks. In 1995 the Charter Group initiated a new monthly and weekly bulletin called EuroSurveillance (now under the auspices of the ECDC) as a way to bring the editors of national surveillance bulletins together from EU member states. Also established by the Charter Group in 1995 was a European training programme for epidemiologists, the European Programme in Intervention Epidemiology Training (EPIET) to produce individuals competent to undertake epidemiological investigations at an international level, which has also been absorbed since by the ECDC.

What was distinctive about this new approach to controlling disease was that it went beyond research collaboration and involved coordinating and harmonising the surveillance and research of communicable diseases between existing national centres of disease control. A new mechanism in choosing what research to undertake was created; prioritising research against the need for it on a European scale and gauging the urgency of research on the increasingly integrated surveillance network. The Charter Group’s network approach was politically sanctioned in September 1998 with A Network for the Epidemiological Surveillance and Control of Communicable Diseases in the Community established by an Act of the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. This was complemented in 1999 by an EU-wide rapid alert system, intended to enable rapid transmission of confidential data between national health authorities in the event of an emergency.

The Charter Group was not the only organised lobby for the future of communicable disease control however. Since 1996, another and competing vision of what the future of communicable disease control would look like in Europe was emerging. It was led by microbiologists for instance from the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, but most prominently Michel Tibayrenc of the Centre d’Etudes sur le Polymorphisme des Micro-organismes in France who were in favour of a central European organisation. The institutions of the European Union paralleled this divide. The European Parliament was in favour of a centre for communicable disease as an institution of the European Union. The European Commission and the Council of Ministers however were in favour of the network approach. In October 1998, a month after the act declaring the network approach as the preferred technique of surveillance, two voluble epidemiologists Weinberg and Giesecke, attempting to staunch the flow of the idea of a central organisation, declared that the ‘idea of a central edifice seems to be politically dead’.

In the wake of the pronouncement that the idea of a central edifice had been defeated, in 1998 Michel Tibayrenc initiated discussions at the International Board of Scientific Advisors in September 1998 and created a European Centre for Infectious Disease (ECID). This was essentially a lobby group, mostly comprised of microbiologists, advocating a European centre. The ECID had a ‘scientific board’ of around 30 people and a steering committee who advocated a European equivalent of the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC f.1946). The US CDC, mirroring a long history of US promotion of European integration, took a personal interest in furthering the cause of the ECID with the head of the CDC’s parasitic diseases division Dan Colley, sitting on the scientific board of advisers to the ECID. Furthermore, public health representatives from developing countries and former Soviet states were also supportive of a European centre for controlling communicable diseases, because the ECID promised to provide expert assistance and exchange information with these nations.

Advocates of both the network approach and the ECID explicitly contested each other’s claims about what benefits each approach had. Leading epidemiologists argued that the proposed coordinating functions of a centre were already being performed by the network approach. The ECID specifically countered this, arguing the network approach alone was not good enough as national centres of communicable disease were ill-prepared to face a major challenge such as bioterrorism and were not fulfilling their aim of preventing gaps and duplications in research. The idea of an initiating but disunited science community mirrors John Krige’s history (1989) of the origins of CERN in the early 1950s. Krige shows how two competing visions existed within the physics community of how European states should cooperate in nuclear physics research. One side advocated a network of nuclear research using existing laboratories and another advocated a European research laboratory and to build there a nuclear accelerator to compete in power with the nuclear accelerators at Brookhaven and Berkeley in the United States. Krige points out the two sides were not in opposition, both saw the value in cooperating, but had different views on how to cooperate.

Tibyrenc’s vision of what a central organisation should do has been reflected in the creation of the ECDC to a remarkable extent. Tibayrenc thought a central organisation would strengthen the effectiveness of the ‘network approach’ but should also take an active researching and surveillance role, and this dual function has been incorporated by todays ECDC. A good example of how the ECDC mirrors the ideas of Tibayrenc is shown in the first actions by the ECDC upon its inception. The ECDC was established concomitantly with the 2005 outbreak of H5N1 Influenza (Bird Flu) and formed part of outbreak investigation teams. In Turkey and Romania, three ECDC staff were on the ground all the time and an ECDC scientist was leading the investigation in Iraq. Here, the ECDC emulated Tibayrenc’s vision of a future ECDC having a mobile scientific staff and his conviction that disease within Europe can only be controlled by a European centre working in non-EU states as well as in EU member states.

This map, produced by the ECDC shows the distribution of the Aedes Albopictus mosquito in Europe and bordering nations. The mosquito, a native of southeast Asia is a vector of emerging diseases in Europe such as West Nile Fever.

We don’t know how far the ECID’s lobbying and Tibyrenc’s efforts directly influenced the political conviction to create the ECDC. But we do know the European Parliament was largely in favour of the centre from the start of Tibyrenc’s lobbying. We know that from 2002, the European Commissioner for public health David Byrne seems to have come on board with the idea, announcing in a speech to the Red Cross and Red Crescent in Berlin, that ‘plans are in preparation to set up a European centre for communicable diseases, to become operational in 2005’. There were other factors involved too that could have triggered or given substance to justifying the need for a centre of disease control such as the threat of bioterrorism after 9/11 or the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak. But perhaps we should not place too much emphasis on these causes. They obscure the fact that the ECID had already lobbied for a European centre from 1998 and anticipated how it would work, as well as the fact that there was already in place a formal European network approach to disease control which took shape from the early 1990s.

According to Colin Talbot (2004), agencies such as the ECDC have been created in the wake of a citizenry increasingly sceptical of experts and politicians. Talbot says that agencies gain public trust through being autonomous from a centralised government. However, this approach mistakenly views agencies only through the eyes of worried politicians seeking to gain trust for expertise. As we have seen however, the ECDC was not founded on a need to gain support from a sceptical citizenry, it was the culmination of many years of lobbying to improve the effectiveness of disease control. Moreover, agencies can be very different to one another. For instance, Waterton and Wynne (2004) argue that upon its inception in 1993, the European Environment Agency (EEA) was in competition with other institutions and organisations, the European Commission’s DG for the Environment in particular. Moreover, they argue that the EEA was not intended to influence policy networks (despite it might have the ambition to do this). Scott Greer’s account of the ECDC differs from this in arguing that the crowded but fragmented institutional landscape of communicable disease control, rather than being a source of competition, is the raison d’etre for the existence of the ECDC, and is the sinews of its future growth. Of course, what Greer misses is that this rationale was developed independently by the Charter Group and the ECID.

This brief account of the ECDC has been all about its origins and not about the ECDC itself. But there is a reason for this. How the origin of a European agency is perceived, or any other type of science-based organisation, changes what we think of that agency in its current form. If looked at from a conventional political perspective, the ECDC looks like a weak organisation amongst what Scott Greer calls ‘a crowded institutional landscape’. However, if we acknowledge that the ECDC assimilated novel and ambitious projects to coordinate the research and surveillance of, and the training for, communicable diseases in Europe, the ECDC represents a new way of controlling and preventing disease which did not exist prior to the 1990s. When the origins of the ECDC are taken into consideration, the ECDC does not look like a beginning in the European control and prevention of communicable disease, but the culmination of a new way to govern communicable disease in Europe.

Bibliography

Krige, John., Why Did Britain Join CERN, in David Gooding, Trevor Pinch, Simon Schaffer (eds.), The Uses of Experiment: Studies in the Natural Sciences, Cambridge University Press, 1989 : 385-406

Krige, J, Pestre, D., Some Thoughts on the Early History of CERN, in John Krige, Luca Guzzetti (eds.), The History of European Scientific and Technological Cooperation, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1997 : 36-60

Waterton, Claire & Wynne, Brian., Knowledge and Political Order in the European Environment Agency. in Sheila Jasanoff (ed.), States of Knowledge: the co-production of science and social order, Routledge, London, 2004 : 87-108.

Talbot, Colin., The Agency Idea: Sometimes Old, Sometimes New, Sometimes Borrowed, Sometimes Untrue, in Christopher Pollitt and Colin Talbot (eds.), Unbundled Government: A Critical Analysis of the Global Trend to Agencies, Quangos, and Contractualisation, Routledge, 2004 : 3-21

Talbot, Colin. Pollit, Christopher. Bathgate, Karen. Caulfield, Janice, Reilly, Adrian, Smullen, Amanda., The Idea of Agency: Researching the Agencification of the (Public Service) World, Paper for American Political Studies Association Conference, Washington DC, August 2000 : 1-22

Greer, Scott L., The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Hub or Hollow Core? Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, Vol. 37, December 2012 : 1001-1030

Tibayrenc, Michel., A European centre to respond to threats of bioterrorism and major epidemics, Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2001, Vol 79 : 1094

Tibayrenc, Michel., The European Centre for Infectious Diseases: An adequate response to the challenges of bioterrorism and major natural infectious threats, (Elsevier) Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 1, 2002 : pp.179–181

Tibayrenc, Michel., European centre for infectious disease, The Lancet, Vol 353, January 23, 1999 : 329

Giesecke, Johan., Surveillance of infectious diseases in the European Union, The Lancet, Vol 348, December 7 1996 : 1534

Giesecke, Johan, Weinberg, Julius., A European Centre for Infectious Disease?, The Lancet, Vol 352, October 17, 1998 : 1308-1309

Rollings, Neil., British business in the formative years of European integration: 1945-1973, Cambridge University Press, 2007

Byrne, David, (Reported by Twisselmann, Birte)., Eurosurveillance, Volume 6, Issue 17, 26 April 2002

Oppenheimer and Churchill

By Jon Agar, on 14 June 2013

I was in the National Archives yesterday and I came across a document that shows that the Oppenheimer trial, one of the most infamous episodes concerning scientists in the Cold War, was being monitored at the highest levels in the UK. The document, a report by Lord Cherwell to Winston Churchill, at the latter’s urgent request, seems to have been overlooked in the (otherwise) exhaustive biographies of the Manhattan Project leader by Kai Bird and Michael Sherwin (American Prometheus) and Ray Monk (Inside the Centre: the Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer) and also Charles Thorpe’s insightful and focused study Oppenheimer.

It started with a telegram, sent by Prime Minister Churchill to his close scientific adviser Lord Cherwell on the 13th April 1954. This was at the height of the Oppenheimer trial, in which enemies of the physicist, convinced that he was Communist sympathiser and angry that he had opposed the acceleration of the hydrogen bomb programme, had sought to remove Oppenheimer’s security clearance. This blow was symbolic. Edward Teller, the hydrogen bomb’s most fervent promoter, recalled in his memoirs his wish to “defrock” Oppenheimer “in his own church”.

Churchill asked Cherwell: “Let me have your views on the matter I rang you about”. Within a day Cherwell had written his three-page memorandum, reproduced below.

Cherwell had only met Oppenheimer briefly, probably three times, but was ready to offer a character assessment. “Robert Oppenheimer is a very good physicist though not perhaps quite so outstanding as some of the papers make out”, wrote Cherwell, “I first met him when he was in charge of the weapon station at Los Alamos in the Autumn of 1944 and found him friendly and unassuming and keenly interested in getting the bombs to work. When I saw him once or twice subsequently he appeared anxious to resume co-operation with England but he was excessively careful not to let out any secrets”.

Cherwell goes on to describe an encounter at an Oxford high table dinner (on the occasion of Oppenheimer’s “somewhat incomprehensible” Reith Lectures), and retails some second-hand coverage of the early stages of the Oppenheimer trial (an article in Fortune magazine that was part of the witch-hunt).

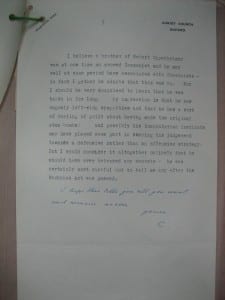

Cherwell reserves judgement somewhat, before concluding that he thought it very unlikely that Oppenheimer was a traitor: “I believe a brother of Robert Oppenheimer was at one time an avowed Communist and he may well have associated with Communists – in fact I gather he admits that this was so”, writes Cherwell, correctly, “But I should be very surprised to learn that he was taken in for long”. He concludes:

My impression is that he has vaguely left-wing sympathies and that he has a sort of feeling of guilt about having made the original bombs; and possibly his humanitarian instincts may have played some part in swaying his judgement towards a defensive rather than offensive strategy [ie radar early-warning systems rather than hydrogen bomb deterrence]. But I would consider it altogether unlikely that he should ever have betrayed any secrets – he was certainly most careful not to tell me any after the MacMahon [sic] Act was passed.

This seems to have satisfied Churchill, although he passes the document on to his Foreign Minister and fellow confidant Anthony Eden: “This may interest you. Let me have it back”.

So what does this tell us that is new? It should not be surprising that the Oppenheimer case was being carefully watched. Britain had its own nuclear troubles: cut out from collaboration with the Americans by the McMahon Act, Britain had had to launch its own crash nuclear weapon programme, one, as Ernest Bevin famously (and probably drunkenly) announced, “with a bloody Union Jack on it”. Furthermore, it had been revealed that the British contingent to the Manhattan Project had contained an extremely effective spy, Klaus Fuchs. There was good reason, beyond Cold War paranoia, to be watchful of security issues concerning scientists and the bomb.

Source: TNA PREM 11/785

the Office of Naval Research and science studies in the 1970s

By Jon Agar, on 16 April 2013

I was in the National Archives at Kew today researching some history of microbiological research and I came across an oddity. It was a paper written by a Martin Blank, issued by the Office of Naval Research’s London branch office in July 1975. It’s title is ‘Interdisciplinary approaches to science – bioelectrochemistry and biorheology as new developments in physiology’. There are several things that odd about it – at least surprising to me.

The paper is ONR-funded science studies – sociology and philosophy of science. The author is a physiologist who wants to know why biology is becoming more ‘interdisciplinary’ and what are the causes of the rise of ‘hybrid disciplines’. He discusses briefly the well known examples of molecular biology and the application of x-ray crystallography to questions of biological structure, but moves on to consider his two more obscure case studies – bioelectrochemistry and biorheology (the science of flow in biological systems).

It starts with an outline of Popper and Kuhn – the usual suspects. But it moves on to cite some authors who have rather dropped out of STS view. For example, there’s a discussion of the geographer RJ Horvath’s notion of the expansion of “machine space” as a master narrative of human history. As machines have exapanded they have encroached on “space that is normally occupied or utilised by people”. Horvath had a paper in Geographical Review in 1974 that I’m tempted to chase up.

There are other odd things, not least the fact that the ONR had a London branch office. Who knew? I hadn’t heard of it before, and I wonder what else it did. I’m guessing that its brief was simply to channel ONR funded research findings to a UK audience. perhaps it funded more sociology and philosophy of science?

Finally, it’s very curious that the paper crops up in the file it’s in (CAB 184 285). It’s being read in the middle of a big discussion about the military withdrawal (or at least relocation) from biological warfare research, and the consequent need to find a role for the Microbiological Research Establishment at Porton Down. In the mix too is the question about how to respond to genetic engineering. Brian Balmer and I are writing a paper on this topic, which is why I came across it. I’ve no idea, yet, if US Cold War-funded science studies is going to be part of the bigger story…

here’s the first few pages of Blank’s ONR paper:

Boxing Clever: Heinz Wolff and the Storage Theory of Civilisation

By Jon Agar, on 5 July 2012

I recently appeared on Resonance FM’s programme The Thread, taking about the history of electrical storage. It was a fun conversation with others including modern literature prof Steven Connor, historian of medicine (and gin) Richard Barnett and Imperial College energy policy expert Philipp Gruenewald. You can hear the programme here.

One story I told was of one my favourite theories of society and civilisation: Heinz Wolff’s argument ‘Society, storage and stability’. It’s rather obscure. In fact, according to google scholar, Wolff’s paper, which appeared in a book called Science and Social Responsibility, edited by Maurice Goldsmith and published in 1975 by the Science Policy Foundation, has never need cited. It would fail the research councils’ “Impact” test spectacularly. But it’s well worth retelling.

Before we start, let us get our Heinz Wolffs straight. It’s confession time! In the programme I got them the wrong way around, and it has taken a little research to sort things out.

In the 1970s there were two of them.

First there is Heinz Wolff, a psychotherapist at the Maudsley, an enormous psychiatric hospital in Denmark Hill. He also taught at University College Hospital. His biography is interesting. (The sources are an obituary here and a pair of interviews with Sidney Bloch that appeared in The Psychiatrist here and here.)

Then, on the other side of London, there is the second Heinz Wolff, the bioengineer, now at Brunel, and later famous for his thick accent and avuncular appearances on TV, especially as the presenter and impresario on the Great Egg Race, in which enthusiastic engineers built Heath Robinson contraptions to transport eggs. That was what science programming used to be like.

The 1975 paper on society, storage and stability is by the egg man not the head doctor. Confusingly, Heinz Wolff the bioengineer was also working in the medical sector. He was funded by the Medical Research Council at the Clinical Research Centre in Harrow, designing monitoring equipment for hospital patients.

At first glance the storage paper looks disconnected from his bioengineering career. However, its ideas and origin make sense in terms of its context. I have argued elsewhere – including here and here – that the ‘long 1960s’ (from the late 1950s to the mid-1970s) were a period of transition for science in society. In particular, the period was marked by a distinct turning inwards: a new critical awareness of the place and roles of science, expertise and authority more generally. The sociology of scientific knowledge, the critical science of science, is one phenomenon of this turn. Another is the radical science movement marked by the activity of groups such as Science for the People.

But another was a more Establishment response that entailed worrying about some of the same issues that fired up the radicals but coming to different conclusions. Maurice Goldsmith’s Science Policy Foundation was one of these responses. It was based in Benjamin Franklin House, near the City. Honorary fellows included Julian Huxley and Lewis Mumford. It was advised by some of the great and the good, including Peter Medawar, Hermann Bondi, Asa Briggs, John Kendrew, Derek de Solla Price, Lord Snow and Alvin Weinberg. Hot postwar specialties (molecular biology, cosmology), meet critical Big Science (Price, Weinberg) and the Two Cultures (Snow).

1973 was a year of strikes, IRA bombs in London and the Cod War. In October 1973, Maurice Goldsmith gathered friends and sympathisers, along with an eclectic bunch of others, including the ex-minister of technology Tony Benn, now in opposition, to discuss science and ‘social responsibility’.

Heinz Wolff spoke, I think, towards the end of the conference. What worried him the vulnerability of complex societies to the disruption caused by an ‘undesirable’ minority. Just as in his body ‘a very large proportion of my internal housekeeping is reduced to immunology … merely to cope with the invasion of what appears to be quite trivial numbers and masses of interfering organisms’, so the ‘more complex society becomes the more vulnerable it becomes to interference by a small number of its members’. Despite the immunological metaphor of invasion, it is clear that what Wolff is referring to here is strikers, the people who can withdraw their labour and derange the system. So, for example, he wonders out loud:

We could try to control he aberrant minority by having very draconian methods of law enforcement. We could, for instance, forbid people in certain sensitive positions to strike, and if they showed any signs of doing so we could threaten to shoot them, or just shoot them. But this, in the kind of society in which we are living, is not permissible. We must, therefore, look for different methods of ordering out society.

At this point, Wolff invites us to think outside the box, or, rather, to have more boxes:

The society I would like to see is one which involves the concept of storage, because storage and stability are almost the same thing. In the same way as a large capacitor is used in the power supply, as a storage device to smooth out variations and give stability to the circuit, so storage in the society sense us also a smoothing capacitor.

Implementing this idea would mean a wholesale change in how we think about and design our technological infrastructure. Technological systems needed to be redesigned so that storage was widely expanded and widely distributed. There was distinct Small is Beautiful aspect to Wolff’s proposals here. The idea is that if all ‘small communities’ were able to store things better, whether those things were energy, water, food, and so on, then collectively society would be more robust. He gives one example (which has recent resonances):

Some years ago in London we had a strike of 700 drivers of the tankers which deliver petrol to local garages, and London more or less ground to a halt. We had a city of 12 million people apparently at the mercy of the activities of 700 people.

So far, so reactionary.

What’s interesting about the argument is that Wolff goes further, extending the argument in to one encompassing all of human history. It becomes a Storage Theory of Civilisation. The important first steps in social and cultural development were not learning to hunt on the plains of Africa, but what happened next. What to do with all that rapidly rotting meat. In Wolff’s words:

When primitive man first roamed the earth he had no security, as such, because he had to find the food which he wanted to eat every day by hunting for it, and in consequence he developed no civilisation as such. He had no art and no culture. He then learned to store things. He was able, therefore, to decouple himself from the variability of nature, and he decoupled himself not only from the variability of food supply but also the variability of the weather. When he got cold, he stored heat in some way, either by lighting a fire or by wearing clothes or living in caves. So he increased the time constant over which he was able to operate independently from the inputs which nature provided for him.