Representing resource use at UCL… using chemistry glassware and electronics

By uccafau, on 20 October 2014

How do you represent the complexities of the resource use of a university using just what you can find in a chemistry lab – and some collective ingenuity?

That’s what Andrea Sella, Joanna Marshall-Cook and I set out to do over the course of last week with the help of Rae Harbird and Stephen Hailes.

The result, Elements, is on show in UCL’s North Cloisters for Degrees of Change, a week long endeavour by UCL’s Sustainability team to explore the environmental consequences of all the world-class teaching, research, collecting, exhibiting, making, inventing and outreach that goes on at the university.

During the research for the installation I learned some interesting statistics. For instance, a typical chemistry fume cupboard uses 10,000kWh of electricity per year (£1,000), and our heating comes from a series of underground pipes.

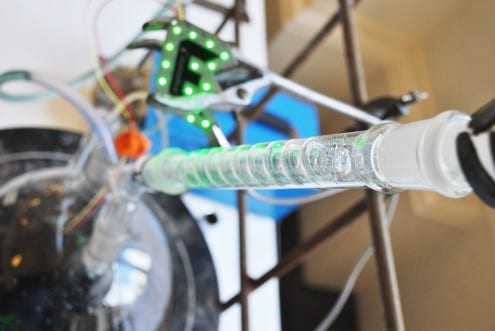

The installation is a visual metaphor for how the university’s heating and water systems work. We often don’t think about the consequences of running a tap, or pouring a bucket down a drain, flushing a toilet, taking a shower. Chemical glassware in all its varied and complex forms provides a perfect toolbox to explore the convoluted system of flows in resource infrastructure. Elements incorporates soxhlets – a type of chemical glassware normally used for extracting liquid from a solid, such as producing essential oils – which act as reservoirs within the system as a whole, just as we act as reservoirs for water either within ourselves or by our actions.

Lots of crazy glassware and – lit up in green and looking suspiciously like UCL Engineering’s logo – an EngDuino computer, monitoring the water level in the system

The crazy glassware installation also has a 5L round bottomed flask and an electric pump – after all, it takes power to heat and move all the university’s water. The flask is like the water infrastructure external to UCL – and is monitored by an EngDuino and sensor, programmed by Rae and Stephen, that alerts us when the water levels are low.

At a time of increasing water scarcity and climate change due to our energy use, it’s important to realise that our actions on a personal scale have a real affect that ripples through the infrastructure that helps us live as well as we do.

- Kat Austen is writer in residence at UCL Mathematical & Physical Sciences

- Elements is on show in the North Cloisters from 10am to 4pm until Friday 24 October

Close

Close