Exploring the environs of Titan

By Oli Usher, on 10 July 2014

Last year, after almost a decade of studying Saturn and its moons, the plasma spectrometer onboard the Cassini probe broke down. This was far beyond its planned lifespan of four years – and what’s more, it may yet have second life, with plans to revive it near the end of the mission in 2017.

In addition to its long service at Saturn, the instrument had also survived the long journey through space that had begun in 1997 – a journey in which it was subjected to the harsh environment of interplanetary space, passed Venus twice and made measurements during Earth and Jupiter swingbys.

Scientists at UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory took a lead role in the hardware development and the science team for the electron spectrometer, and while it is no longer operating, there is still plenty of work to do on the data it gathered. In particular, the detector’s studies of Saturn’s moon Titan are expected to yield further secrets.

Cassini – a NASA-led Saturn orbiter – released an ESA-built lander called Huygens to land on Titan when it arrived in the Saturn system in 2005. Huygens took the first ever picture on the surface of a body in the outer Solar System. (It is also the only landing to-date on another planet’s Moon.)

But what the Cassini probe is able to do from space, which Huygens could not on the ground, is analyse the complex interaction of Titan’s thick atmosphere with the magnetic field of Saturn. Titan is surprisingly Earth-like, despite being quite small. It has a thick atmosphere and an icy, rocky surface, as well as mountains, seas, lakes and rivers (though these are made of liquid hydrocarbons such as methane, rather than water).

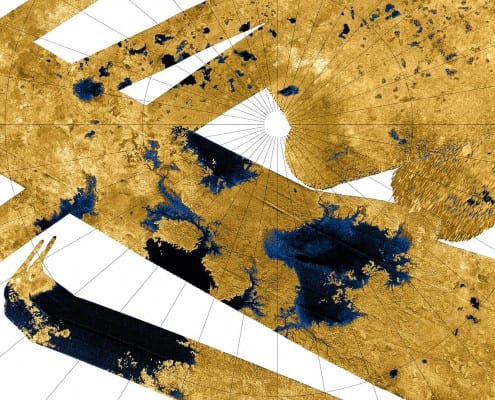

Hydrocarbon lakes on Titan, observed by the radar onboard Cassini. Radars do not produce colour images – in this picture, the smooth areas (lakes and rivers) have been coloured blue to improve contrast. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS (public domain)

But while Earth’s atmosphere is cocooned well inside our planet’s magnetic field, protecting it from the Solar wind and from interactions with other Solar System bodies, Titan’s is not. Titan spends most of its orbit within Saturn’s hot magnetosphere, meaning its atmosphere interacts with the giant planet it orbits, including the plasma and magnetic field that surrounds it. This makes Titan’s atmosphere very ‘leaky‘ compared to Earth’s.

A recent fly-by of Titan by Cassini while the moon was orbiting outside Saturn’s magnetosphere reveal another intriguing phenomenon: the Solar wind blowing part of Titan’s atmosphere away, leaving a comet-like plume of gas coming from it.

UCL is hosting the Alfvén conference this week, in which experts in planetary magnetic fields and plasmas are coming together to discuss the latest results from missions including Cassini.

Close

Close