MIRRA+ By Peter Williams

By Elizabeth J Lomas, on 22 October 2020

… we are pleased to announce that the MIRRA project has obtained further funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council. In our first project we focused on understanding the information needs of care experienced individuals, and this enabled us to build a set of recommendations around the creation, management and ongoing accessibility of children’s social care records. This had the aim of better supporting the care experienced to enrich their memories and their sense of identity’. Some work from this first phase is still ongoing. However, with this new funding we are now developing a set of specifications that can underpin a new record-keeping system for use in child social care that takes our recommendations into account and which centres the needs of the person in care. Crucially, it will be designed to provide better opportunities for care experienced individuals to contribute to their files. We are delighted to be working with the commercial company OLM Systems on this. OLM are expert software developers who work with public services and the wider care sector. This next phase of the work will be known as MIRRA+. The result of the research will be an open-source specification for a participatory digital social care recording system.

As previously, we will also be working with care-leavers (as co-researchers), social care workers and information professionals who will be using the system. We wish to capture their views on what the system should look like, how it should function, and what features would work for them.

I keep saying ‘we’ of course, but in fact I should introduce myself. I am Peter Williams, the new Research Associate working full time on the project. I have worked as a researcher at UCL on various projects since 2004 but am delighted to have this opportunity. In addition, I will be working with Anna Sexton. Anna worked on the initial pilot project that was the forerunner to MIRRA. In my case, at the time of the first MIRRA I was working on a British Academy-funded study looking at the role and impact of mobile devices on the lives of people with learning disabilities – the last of a long line of projects working with this group. However, I kept up to speed on MIRRA, partly because it was similar to my own work ‘participatory’ also in that those involved were not mere research ‘subjects’, but ‘participants’ (if not ‘co-researchers’) and partly because I shared an office with the amazing Victoria Hoyle who worked on MIRRA full time. It will be very hard to match her expertise, although I hope I have the same enthusiasm, and will certainly try my best! Elizabeth Shepherd and Elizabeth Lomas continue to work on MIRRA too.

Meanwhile, watch this space for more news on our progress!

Up Close and Policy! Care leavers’ access to childhood records: the British Association of Social Workers, Ofsted, the Care Leavers Association and MIRRA project team

By Elizabeth J Lomas, on 12 October 2020

As you know, MIRRA is trying to make change surrounding social care recordkeeping processes including access and ownership of those records by care leavers. In addition we have been looking at the wider information networks that help care leavers make sense of their lives. This is a journey, which many of our MIRRA research participants have been working on for a very long time. A critical intention of MIRRA from the outset, was to provide an evidence base to help facilitate critical policy changes for the care leaver community. Clearly this work has had a much greater impact because of the role of care leavers as co-researchers at the heart of the project advocating for their needs. We have been grateful for the support of the Care Leavers Association. In addition, from the outset we were able to get key stakeholders involved as advisors.

On Wednesday 14th October, we will be discussing the MIRRA policy journey with some critical players – Darren Coyne (Care Leavers Association), Luke Geoghegan (British Association of Social Workers) and Matthew Brazier (Ofsted). Social workers have been keen to reconsider aspects of their recording processes and the importance of the child’s voice in recordkeeping. In August BASW, drawing on MIRRA guidance, published top tips for recording practices (https://www.basw.co.uk/resources/recording-children%E2%80%99s-social-work-guide ). In addition, Ofsted have taken very seriously the impact inspections can have on recordkeeping processes. This was a great blog post from Ofsted on records https://socialcareinspection.blog.gov.uk/2019/07/24/what-makes-an-effective-case-record/ . MIRRA has reached out and tried to make a difference to on the ground practice, both through the traditional networks of Whitehall but in addition through other critical players from professionals through to charities and local authorities.

We hope that some of you might want to come and join this discussion on policy making within the context of MIRRA. It is on Zoom at 1-2pm Wednesday 14th October. Please sign up at https://upcloseandpolicycareleavers.eventbrite.co.uk.

Spreading the word!

By Elizabeth J Lomas, on 4 October 2019

We have been trying to further spread the word about our recordkeeping recommendations for local authorities, information and data professionals, and social workers, which are that:

- Records should be co-created by all those involved in a child’s care. They should include the voices of children themselves, taking into account their life-long needs for memory, identity and justice.

- Best practice guidance for records creation and management should be establishedfor all organisations with safeguarding responsibilities and guardianship of children’s memories.

- New standards for access to records for all care-experienced persons should be developed. New standards should address the rights of care-experienced people and the responsibilities of institutions.

UCL has issued a press release at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2019/oct/childrens-voices-omitted-care-records-ucl-study-finds . We are delighted that this press release has already been picked up by The Conversation who have published a piece at: http://theconversation.com/care-leavers-trying-to-access-childhood-records-is-distressing-and-dehumanising-124381. The piece draws out the distressing and dehumanising nature of some recordkeeping practices across the social care system. In addition, it highlights the value of good recordkeeping. We are pleased to report that Community Care produced a piece highlighting the recommendations: https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2019/10/03/childrens-voices-largely-absent-care-records-causing-significant-distress-study-finds/ . Finally Elizabeth Shepherd was interviewed and discusses the project at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p07md69m (please note she is featured 2.22.50 in).

All of these pieces are made particularly powerful by those participants who were quoted speaking of experiences accessing their records and the highs and often lows of seeing what had been captured. It is their testimonies that highlight the significance of recordkeeping, whereby childhood memories should be captured and made available as a basic right that underpins lifelong wellbeing.

We hope that others will continue to engage with this important debate.

A goodbye, thankfulness and new beginnings

By Victoria Hoyle, on 23 September 2019

Research often feels like something that happens behind closed doors. Over the two years that I’ve worked on the MIRRA project I have spent many hours alone in my office (or at my dining table!), just me, a computer screen and the clack of my keyboard. This is undoubtedly where a lot of the work of thinking, analysing, understanding and writing has been done; but it isn’t where the meaning or satisfaction in my job has come from. That has come, without fail, from the amazing people that I have worked alongside and from the change we’ve started to make together. When I was doing my PhD I often quizzed myself about my decision to go into research, and worried that becoming an ‘academic’ would take me away from the real world and the real life concerns of people. I’m inexpressibly grateful that my first full-time job as an academic researcher proved those fears were wrong, in so many ways. Research is what we make it, and with MIRRA we have all had an opportunity to make something powerful and heartfelt.

That’s an emotional way to begin this post, but it seems fitting since MIRRA has been an emotional project: it’s about memory, identity and our need to understand ourselves, which are all very emotional things. I’ve often felt full of feelings while working on it. I am full of feelings now as the project, at least this phase of it, comes to a close. The current funding for MIRRA finishes in mid-October 2019, which means that my role as Research Associate is almost over. I will be leaving UCL at the end of this week (28th September), to take up a new job at the University of York. This is incredibly sad for me, because I will miss working with everyone in the research team so much; but it is also very exciting, as the new project I will be working on also promises to make a difference to people’s lives.

The MIRRA Research Team. Left to right: Linda, John-george, Darren, Rosie, Brett, Isa, Gina, Me! (Victoria), Sam, Elizabeth (UCL), Emmanuel and Elizabeth (UCL).

I am grateful and humbled that I have had the opportunity to work with my care-experienced colleagues on MIRRA. Prior to starting on the project I had very little knowledge or understanding of child social care, and no personal experiences. I was an outsider, but people welcomed me in. I would like to particularly thank the core and extended research group – Darren, Andi, Gina, Linda, Isa, Rosie, John-george, Jackie, Emmanuel, Brett and Sam – but also all of those who shared their life stories or experiences and placed their trust in me, in person, by email or on Twitter. Practitioners and other researchers have also been very generous, both with their time and their thoughts. It’s safe to say that while I have learnt a lot about care and care experiences over the last two years, I have learnt even more about how to be a good researcher and a good human.

MIRRA doesn’t end here though! The other members of the research group at UCL, Elizabeth Shepherd, Elizabeth Lomas and Andrew Flinn, will be picking up the reins and carrying the work forward. They will be continuing to work with legislators and regulators on improving recordkeeping and access to records, and creating and sharing guidance for care leavers and practitioners. Twitter and the website will still be updated. They will be joined by a new colleague, Anna Sexton, who will be leading on follow-on funding applications to extend and expand the work. Anna isn’t completely new to the project, as she worked on the original pilot study back in the summer of 2017.

We are currently waiting to hear about another year’s worth of money from our current funder, the AHRC, which would allow UCL to start developing a recordkeeping system for social workers that focuses on memory and identity rather than risk and performance management. If that bid is successful the project will start early in 2020. The team is also beginning to discuss the next large scale bid, which will widen the research to other services and agencies who have similar record-keeping issues including mental health provision, criminal and youth justice, immigration and adult social care. The aim is to keep records high up on people’s radar, and to emphasise the role they play in shaping our lives as both individuals and as citizens.

You can contact the team with your thoughts and queries:

Elizabeth Shepherd – e.shepherd@ucl.ac.uk

Elizabeth Lomas – e.lomas@ucl.ac.uk

Anna Sexton – a.sexton.11@ucl.ac.uk

Andrew Flinn – a.flinn@ucl.ac.uk

If you would like to stay in touch with me and my future work, you can find me on Twitter as @Vicky_Hoyle, or contact me via email at victoria.hoyle@york.ac.uk.

Take care everyone, and thank you again.

Caring Records Management: A Case Study

By Victoria Hoyle, on 19 September 2019

This post has been kindly contributed by Michelle Conway (IMS Team Manager (Records)) and Imogen Watts (Corporate and Digital Records Manager) from Gloucestershire County Council.

Recently, at the MIRRA Symposium, we were reminded that organisations have a lifelong responsibility as the corporate “parents” of care-experienced individuals to safeguard their records and make this information available to them. While we, as information professionals, would wholeheartedly agree to these principles, the reality is that record-keeping and record-sharing practices historically have not always matched.

Our organisation, like many others, has not done things perfectly. However, over the last four years, we have been running a project to improve the accessibility of our historical childcare files and the information within them.

The Historical Children’s Records Project (HCRP) began in March 2016 with the aims to:

- Identify historical childcare files held across the council’s estate and transfer them to the central Records Centre where they would be indexed in our records database and placed into secure storage;

- Improve the indexing of historical childcare files already stored in the Records Centre. No small task, considering there were over 80,000 of these in storage!

How was this born, you ask? Well, the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse’s (IICSA) requirement that organisations make children’s records accessible for inquiries (plus the subsequent moratorium on the destruction of children’s records) prompted us to take a long hard look at how records were being managed and to acknowledge that “J Smith” as a file title was an inadequate identifier. An external audit of the availability of the council’s safeguarding records also highlighted issues of identifying what and where records were being kept and the impact of this on responding adequately to subject access requests. The council judged that the risks were high enough to warrant funding for a project team and we have been able to secure funding on this basis year on year.

Initially, the project felt like a Pandora’s Box: visiting 55 council properties has demonstrated the weird and weirder places that uncatalogued records have been stored (including in the kitchen sink and roof rafters), with over 12,000 files transferred to the Records Centre in the project’s first year. Conducting records surveys as part of office moves and decommissioning of premises is now becoming part of business as usual, as we’ve recognised that if we aren’t proactive, records will literally become hidden.

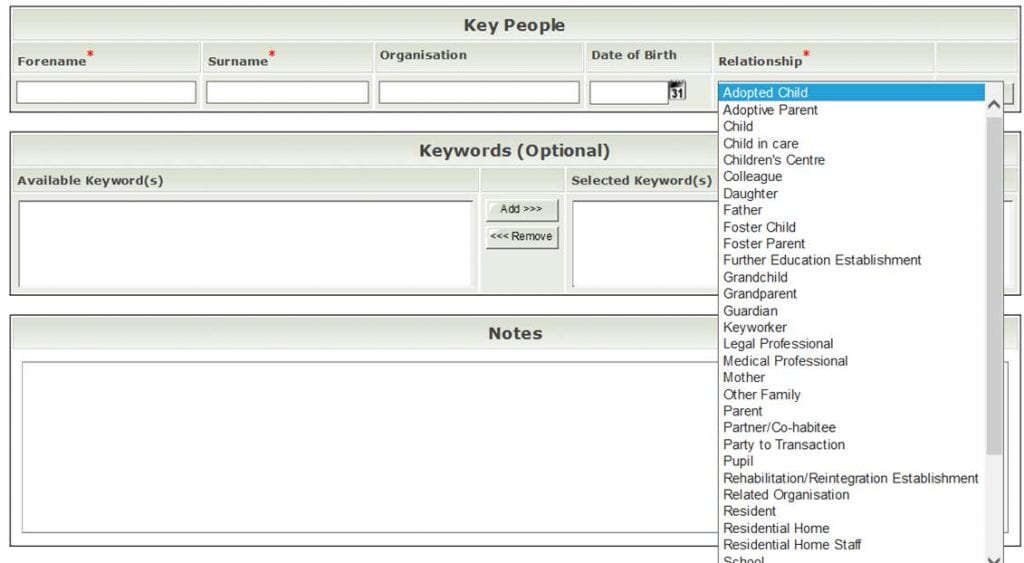

The indexing process has been equally eye-opening. Taking a risk-based approach, we decided to prioritise administrative and case files from residential children’s homes. Records are indexed in our Records Centre database, RAFTS, and as we reviewed the file entries, we found that whilst files had basic metadata attached to them, this metadata was incomplete and didn’t accurately identify all the individuals whose information was contained in the files. For example, a case file for J(ane) Smith would primarily contain information about her but it would also hold key data relating to her parents – e.g. Peter Smith -; siblings; and caseworkers. We added key metadata (names; DoBs; relationships) to the database entries to ensure that if someone searched for information on Peter Smith, Jane’s file would come up in the search results, as well as any files where Peter was the main subject.

This work has positively supported the work of our Information Requests team, as it provides them with a greater certainty that when they search RAFTS, they are signposted to the information they need. This helps ensure care leavers are given all the information they are entitled to.

Through the work to improve the historical file index entries, the project team has amassed a wealth of knowledge on social care files through the years and the issues that have been rife in historical information recording practices – which vary dramatically over time. We’ve decided to use as much of this knowledge as possible to inform and improve current and future practice.

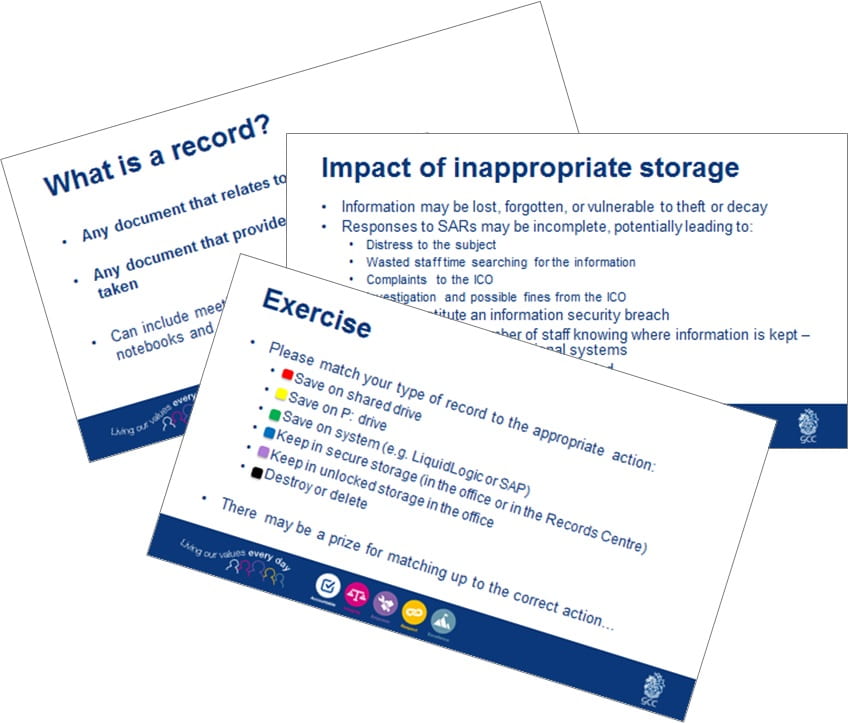

Since November 2018, representatives from our Records Management and Information Governance teams have been embarking on a programme to deliver information management training to staff across Children’s Services – from admin staff to practitioners to managers and service leads. Part of this training covers appropriate storage of files, what technically counts as a record, and (for practitioners) what information should be recorded – including how, where and when. The HCRP project team’s knowledge on historical issues in information recording has been invaluable to help identify potential gaps and to ensure we cover these.

Training is being delivered across the Council, to everyone involved in child social care recordkeeping.

This probably all sounds a bit dry, as information management is usually perceived to be… So we’ve done our best to try to make the training as much fun as possible. We get everyone involved and actively participating in tailored activities, including a game where you win a chocolate (of the mini variety) if you correctly match the document type to the appropriate storage location, a “what would you do?” exercise around a (fictitious) email being sent to the wrong (fictitious) person, and a handful of cartoon characters as case studies – for example, we’ve had Paddington Bear asking for his files (he was in foster care with the Brown family after all), and it turns out we found some (fictitious) files in a (fictitious) basement instead of the Funnybones skeletons (remember them?).

The feedback we’ve received from this training has been overwhelmingly positive, which is great to hear and shows that our aim of making it both fun and informative is working. Our main concern remains making sure we have an impact on the way things are done. We have seen some changes already, particularly around secure handling of information, so we seem to be on the right track. It does look like it might be quite a long road, especially since the goalposts shift slightly when new information comes to light, for example we’d now like to tie in the recommendations from the MIRRA project and help the council adopt that child-centred way of recording information. It may take some time to get these changes planned, approved, understood and embedded, as significant changes tend to, but as long as we’re moving forward, we’ll still be making progress and improving things as much as we can. Sometimes small steps are all that you can take, but as long as we keep our eyes fixed on the end goal we’ll get there in the end!

More information about Gloucestershire’s Historical Children’s Records Project is included in our downloadable best practice case study leaflet. Later this year MIRRA will release a set of Principles for Caring Recordkeeping and a toolkit to support organisations to meet them.

Weaving together all our stories

By Victoria Hoyle, on 5 September 2019

I’ve spent the last few weeks working on research articles and other writing projects. As MIRRA nears the end of this research phase 90% of my to-do list involves long hours spent synthesising our findings and key messages, producing reports and putting together guidance documents. It can be draining work. So I was happy to see an exciting distraction in my inbox this morning: an email from Tabitha Millett, the artist who came to our Symposium in July, sending a batch of photographs from the day.

I should backtrack and explain. Many months ago when we first started to discuss the research Symposium we decided we wanted to have some sort of creative element. We wanted to have some way for people to capture and share their personal experiences of child social care records, whether they were care-experienced, a social worker or an information manager. We settled on the idea of working with an artist, who would collaborate with symposium attendees to produce a piece of art during the breaks and lunchtime. Having secured some funding from UCL Impact and Engagement (thank you!) we found Tabitha, an artist with experience of doing this kind of work in conference settings and with diverse communities.

She suggested we create a textile piece that soon became known as The Plait. The concept was to invite everyone attending the conference to bring a small item or piece of fabric that resonated with their experiences of social care records. They could then stitch this on to one of three strips of felt fabric. Whatever they brought had to be something they were willing to leave behind, to become part of the final piece, so it could be symbolic rather than original if they preferred. For people who didn’t bring anything along, we supplied a lucky dip bag of fabric scraps that could be personalised. We also had fabric pens that could be used to annotate pieces, or to draw directly onto the base fabrics.

The backing fabrics were white, grey and black, to symbolise the record itself: the white paper, the grey text and the black redactions that people often receive. By writing and stitching feelings, opinions and experiences onto the fabric the aim was to capture everyone’s stories, and reflect on the value and meaning of records.

Some of the individual contributions were incredibly moving and powerful. One person attached the pink legal tape that had bound up their social care file, while another attached a bear key ring to symbolise the teddy bear that they had not been able to take with them into foster care.

Attendees also reflected on resilience and how past experiences had helped to make them who they are today. Others took the opportunity to ask practitioners and others to remember the power that records have in people’s lives.

“I am today the sum of everything that has happened to me…Please do not erase any part of me” Contributions to The Plait

At the end of the day the strands of The Plait were laid out for all to see, and then during the final session, while people shared stories about what they had contributed with the rest of the audience, it was plaited together into a braid. As the braid formed some people’s contributions were hidden inside, while others peeped out of the weave. It was a reminder of how all of our stories are woven together, but whereas some are visible, others are hidden. But even hidden they are still there, still vital and important, still sharing the same space.

As well as giving us lots to think about and talk about on the day, The Plait is also a lasting tangible reminder of the themes of MIRRA and of the importance of the research. The idea is that it can be unwound and added to at future events, and can be displayed to tell people’s stories. If you are interested to have The Plait at your event, to add to or display it, let us know.

Reflecting on the MIRRA symposium, 18th July 2019

By Victoria Hoyle, on 30 July 2019

Almost two weeks have passed since we welcomed over 100 people to UCL for a day of presentations and discussion about access to records and child social care recordkeeping. Care leavers, researchers, social care practitioners, regulators, policymakers and records and information professionals all came together to share their experiences and thoughts. It was a powerful, emotional and extremely productive event which gave me lots of things to reflect on. So much so that I have struggled to collect my thoughts and unpick my feelings in the days since.

In large part I think this is because conferences, symposiums and research events are not always (not even often) about feelings and emotions. They are usually focused on findings and outputs, on presentations and publications. While the symposium included elements of all of those things, it was first and foremost about hearing and responding to the voices of experience. Throughout the day 11 of our care-experienced co-researchers shared their experiences of accessing and reading their care records. Each focused on the aspect of the MIRRA research that has meant the most to them. Linda spoke about reliving the day she was taken into care through her records, and the judgemental, inhumane way she was described as a child. Jackie shared images of her heavily redacted files and spoke about her campaign to change the way Birmingham City Council provides access to records. Brett talked about his ongoing search to find his care records, including the frustration of being told by multiple local authorities that they have no trace of him. John-george described the shock of receiving his file without warning through the post, only to discover that his voice was completely absent from it.

The MIRRA Research Team. Left to right: Linda, John-george, Darren, Rosie, Brett, Isa, Gina, Victoria (UCL), Sam, Elizabeth (UCL), Emmanuel and Elizabeth (UCL).

I know from the feedback cards filled in at the end of the day that listening to these testimonies was very important for the practitioners present, many of whom had never heard a care leaver speak about records before. Feelings and practice were brought together in a way which, we hope, will inspire people to think differently about the day-to-day actions of recording or redacting. The professional audience was left with some clear and vital messages about how things could be improved. Rosie, a social worker herself, exhorted the social workers present to be mindful of language and tone when writing records, while Sam was passionate in arguing that everything a corporate parent does, including creating or providing access to records, should come from a place of love. Gina shared her positive access to records experience and suggested that psychological and practical support should be provided for every care leaver who wants it, no matter their age. Listening to everyone speak so eloquently and forcefully made me feel incredibly proud and honoured to be able to speak and work alongside the whole team.

In addition to reaching the hearts and changing the minds of those in the room, our goal has always been to embed long term change. There were signs that this may be happening. The event began with a keynote address from Elizabeth Denham, the UK Information Commissioner, who set the scene by acknowledging that information rights, and especially rights of access to information, are about people. We were particularly pleased to hear her say that subject access requests from care leavers, made under GDPR and the Data Protection Act, should be treated with sensitivity. She talked about discretion in making redactions, and about the importance of support and care during the process. When taking questions from the audience she reiterated that organisations who hold care records needn’t be risk averse: the Information Commissioner’s Office has never taken action against anyone for the use of discretion while processing care files. These were very important points, which we intend to continue discussing with the Commissioner’s staff at the ICO as the basis for best practice guidance.

Later in the day we heard from Luke Geoghegan, the Head of Policy and Research at the British Association of Social Workers, about their commitment to publish new practice guidance on recordkeeping, written in collaboration with us. During the same session David Holmes, the CEO of the charity Family Action, spoke about the work we are doing together to create an interactive website for care leavers (and adopted people) to support them to access and understand care records. We will be contributing content and advice to this new site, which will be called Family Connect and is due to launch later this year. Last but certainly not least Darren Coyne shared the latest updates from the Access to Care Records Campaign group, who are currently producing National Standards for Access to Records for Adult Care Leavers. We have been supporting this work, which we hope will be endorsed by the Department for Education.

At the end of the day, feeling both exhausted and elated, I was left with a strong conviction of the value and potential of research for contributing to positive change. This change might be at the level of the individual, who alters a small element of their work practice, or at the level of national policy and regulation. In both cases, it seems to me, the change arises not only through the research findings but by connecting those findings to feelings. For me the symposium succeeded the most in demonstrating why MIRRA matters, through the voices of the people it matters to most.

The phone rings: A case study

By Victoria Hoyle, on 25 June 2019

This post is written by Craig Fees, archivist at the Planned Environment Therapy Trust Archive and Study Centre, 1988-2018.

The phone rings. Out of the blue: A former child in residential care, from a place whose archives we hold. This is already special. Here is a voice reaching sixty years into the past to bring this children’s community into the present, and bringing a subsequent lifetime with it.

He’s heard we may have his file. We do. Can he come to see it? He can. He’s partly disabled; he will take the train to a nearby station – we have a small rural one I recommend. Can I recommend a taxi firm? No, I will pick him up (and take him back!). We have onsite accommodation if he wanted to stay overnight. No, he wants to come up and go back on the same day. This first conversation lasts the better part of an hour – because I know something about the place and know the names of members of staff and even fellow children as he mentions them, and he wants to talk to someone for whom the place is important and has meaning. It’s fascinating, and I ask whether he might possibly be willing to record such a discussion, if there’s time, when he’s here? The recording would be confidential unless or until he agreed otherwise, having had a copy of the recording (we don’t always have the resources to provide a transcript; but that would be ideal). I explain how it’s held securely, and that people either could or could not see it, depending on what he wished; it would be entirely in his hands. But there might not be time, and it might well be something he would not want to do anyway. But I do want to convey that what he is saying is important, and would be of immense interest to future generations. Or should be! I want him to know that he and his experience are important.

We talk about data protection, and what I will do to make the file available to him: I will go page by page through it, with an eye for third party information which might need to be redacted; I explain the legal parameters guiding redaction; and I explain that because the file is a private document about him, and from my point of view is none of my business, a) once I have been through the file I am unlikely to remember in any detail what is in it, because I will be reading it instrumentally and not for information about him or his life, and b) I will not redact anything unless it is absolutely legally necessary, because the more detailed and complete the record I can put into his hands, the more value it is likely to have for him. I ask him for three things before I start: some proof that he is who he says he is, so that I don’t release information to someone I shouldn’t; any information he can share about who I might encounter in the file (family members; fellow children; foster carers…), and if he can let me know whether any are alive or dead; and formal permission to go through his file. Of course he is unlikely to say no to the latter; we both understand that. But it is important to me that he is the one who makes the decision, and gives the permission for this stranger to go into his intimate childhood. It is not just a formality. Are there any charges? No, although as a small charity we never say no to donations. But we don’t want anything to stand between an individual and access to their file.

I meet him at the station. We readjust the car to meet his physical situation. I tell him we have a twenty-five minute ride. We talk: it’s beautiful countryside; he’s come from London. He asks about me, about my background and where I’m coming from, so we talk about that. I tell him I have set up my office with his file, and am happy to be in there with him, or to shut the door and let him have it to himself. He won’t be disturbed if he doesn’t want to be. When we arrive I make coffee and biscuits. I explain the very few redactions I’ve made, how he will know when he comes across them, and what they mean: for example, in the filing system in his childhood children from the same authority often had papers mixed together, or the children were bundled together into a single piece of correspondence. Since he knew who he travelled to and from the place with (and has mentioned them), I would not remove that kind of information. But where there were personal details about the other child or their home situation, for example, I would.

He elects to be alone with his file. The phone is unplugged, there are no limits on time, and there are no other visitors expected. I will be somewhere around if he needs me. Eventually, he emerges and we talk. He shares his views on his file, and his child’s eye view of its depictions. There are factual inaccuracies in it. Some things have fallen into place for him. We don’t record; it’s not appropriate. But he invites me to meet him some time for coffee in London. I take him back to the train. We email. We meet in London, and he talks about the place some more, about his life, about the experience of accessing his file, and something of what he learned. He has a second hot chocolate, and I have a second coffee. London is his home ground, and he makes sure I know the best route back to the train. I am in the loop when I hear, from a member of his family some months later, that he has died.

Each request is unique, comes differently, and unfolds in its own particular way. But if done well the underlying philosophy of welcome, of being at the service and disposal of, of adapting to, of making possible, of conveying the meaning and significance of, of learning about and from should be consciously or unconsciously experienced by every person seeking their file, as is a sense of sharing responsibility and of working together. The ultimate source of one’s orientation as an archivist is love, or, more simply, a profound respect and treasuring of people, of records, and of the possibility when they come together; with a healthy respect for boundaries, and for the potential of traumatic experience to spring surprises, including the surprise of having no bearing at all; the knowledge that archivists are not therapists, but people; and with a fundamental understanding that whatever the emotional dynamics of the encounter with their records, that experience is theirs, and not ours. We are guests in their lives, and the unique privilege of the archivist is to set the stage for their encounter with their file; to provide an environment which is welcoming, informed, and safe; and to be available if and as called for, with the willing understanding that one may not be called or needed at all. Which is excellent; to be invisible and forgotten is a privilege as well.

How can practitioners change records for the better?

By Victoria Hoyle, on 17 June 2019

Social care recordkeeping is a complex system, with many dozens of people involved in contributing to, preserving and providing access to just one person’s file. Multiply that by the 72,000+ children and young people currently in care and there are 100,000s of practitioners involved in producing and maintaining social care records all across the country. If we’re going to change and improve recordkeeping practice then reaching that audience is a high priority. Earlier this year we secured an additional £15,000 of funding for the MIRRA project to share our research more widely and talk to social work and information professionals about records’ issues and why they matter.* We started working in close partnership with the British Association of Social Workers (BASW) and the Archives and Records Association (ARA) to reach out to sectors that very rarely talk to one another.

As part of a programme of events (including our sold-out conference on 18th July – you can join the waiting list if you didn’t manage to get a place) we recently hosted two workshops with practitioners in London and Manchester. With over 60 people attending in total, from a range of backgrounds in the public, voluntary and private sectors, from children’s home managers to information governance managers, we generated a lot of brilliant and interesting discussion. Many of the topics will be familiar: the challenge of depleted budgets and resources, both for Children’s Services and records work; the complexities of digital recording systems; and the legacy of less-than-ideal practices from the past. At the beginning of the session we premiered a video we have made about the MIRRA project with our care-experienced research team (link coming soon!), which helped to keep the debate rightly focused on the impact records have on care-experienced people.

A visual minute taker joined us at both events to illustrate the conversations as they developed, and help us to see both consensus and actions emerging. These artworks highlight some of the key priorities the workshops identified, which in turn will help us to develop the resources practitioners need for better recordkeeping. The first step was convincing people they needed to act, and now the second will be providing them with tools to help. This is something I will be focusing on over the next five months as the project comes to the end of its first phase. Here are just some of the most critical lessons we learnt during the sessions:

- Social care teams and information/records management teams rarely work together or communicate regularly. They inhabit very different worlds, culturally and practically. All of the guidance we produce has to speak to both sectors and encourage practitioners to work together. The less fragmented recordkeeping is the better.

- Training in recordkeeping is needed at all levels. We’ve often talked about training for social workers or records managers, but the complexity of the system means we need a holistic approach. Everyone who works with children and young people or their records should have training.

- The regulatory and inspection regimes provided by Ofsted and the Information Commissioner’s Office are very important but can have a negative impact on recordkeeping, creating risk averse and inflexible approaches. Children, young people and care leavers get squeezed out by processes that are designed to fit a standard rather than support the individual. Activism is needed to work with the regulators to establish child-centred, care-centred recordkeeping as best practice.

- Thinking about records in terms of retention schedules, performance management and accountability doesn’t properly reflect their importance as memory and identity resources. If we shift our thinking about who records are for and why they are so vital then we can make small changes that support people. For example, we can write records in children’s own words rather than paraphrasing them, and we can extend the time we keep them beyond the minimum retention to the life time of the person they are about. Small actions like this, taken on a case-by-case basis, can make a huge difference.

Thanks to everyone who participated in the workshops. I’m looking forward to sharing the resources we create very soon. Watch out for the link to the short film when it’s released and do share it on social media.

*This funding was from the UKRI’s Higher Education Innovation Fund (HEIF), via UCL’s Innovation and Enterprise programme.

“Why was I in care?”

By Victoria Hoyle, on 4 June 2019

For the past four months I have been working on coding and analysing the interviews, workshops and focus groups we’ve conducted with nearly 100 care experienced people, social workers, records managers and others involved in child social care recordkeeping. There is a huge amount of information to sift through and categorise, but the help of our analysis software NVivo I can now see clear themes and shared experiences emerging. One thing that has struck me time and again is how often a care leaver says they wanted to access their records to find out why they were taken into care, or to better understand the circumstances around going into care. Information governance practitioners have also told us this is the most common reason why someone makes a subject access request for their records.

Recent research in Northern Ireland suggests that the struggle to answer this fundamental question starts whilst someone is in care. Linda McGill and colleagues have demonstrated the high numbers of children and young people who are confused about their personal circumstances and why they are in care (McGill et al, 2018). McGill’s research suggests that social workers struggle to communicate a consistent and honest response to questions from children, who often hear different stories from different people at different times. This uncertainty may be internalised as feelings of blame, shame or fear (Hughes, 2009). It can lead to the construction of damaging stories that make sense to the child but are far from reality. For example, that they are to blame for being taken into care because they were naughty or because they failed to stop a bad thing from happening. Our own research shows that these feelings and stories stay with people throughout their lives. Several of the adult care leavers who have contributed to the MIRRA project have spoken about it. They wanted to access their records to find out why they were taken into care in order to dispel these lifelong feelings of guilt and fear.

“Why was I taken into care?” It sounds like a simple question, but it’s anything but. Quite often the answer is complex and cumulative, and difficult to locate in an individual’s records. As it often forms part of documents used in care proceedings it may be wrapped up in legalese, jargon and references to legislation. Or alternatively, in some more recent digital records, it may be recorded using tick boxes that identify ‘factors’ in the social workers’ decision, lacking nuance and narrative. At the point of access the information is also highly likely to be redacted because of the role that ‘third parties’ such as parents, siblings and other carers have played. As a result it can be one of the great unanswered questions of the access process.

When people do get an answer the positive emotional and psychological impact can be enormous. Our co-researcher Gina has described how seeing her records finally helped her to realise that being in care wasn’t her fault:

“…right through up until I got my file I thought it was my fault, because I was a naughty child or whatever. It was only when I read through my file that it made me realise it actually wasn’t my fault and that helped me to move on. That was really important for me.”

Another of our interviewees described how his brother still blamed himself over twenty years later:

“…my brother… he built this idea up that we all went in to care because [of him]. That was the narrative that the whole family had got a grip on. But when I accessed my care files that was just the reason for the initial referral. When social services came in it was then another thing and another thing and another thing, there was sexual abuse and then we went in to care. He didn’t know any of that.”

I’m now writing guidance for practitioners about how to approach recordkeeping with love, from a human-centred perspective and plan to make two key recommendations around this critical issue. Firstly, we will be echoing McGill et al (2018) by highlighting the need to talk to children and young people sensitively and often about their life circumstances, so that they develop an organic understanding of what has happened and why. Secondly, that records about care decisions should be written as if they were being addressed to the child, so that they are clear and understandable. Thirdly, by urging those who handle requests for access to records from older care leavers to treat information about why they were taken into care as their information, even where it also touches on other people (‘third parties’). As our co-researcher Isa puts it:

“…when somebody goes in to care nothing is third party. If it’s the reason why you went in to care, it’s not third party.”

Confronting the difficult reality of why someone is or was in care through these recordkeeping practices could make a real difference to how they see themselves and remember their childhood.

Close

Close