‘African Apocalypse’: Unveiling the trail of colonial violence and its enduring legacy

By IOE Digital, on 22 December 2022

Film screening and debate at University College London, 15 December 2022

22 December 2022

By Sabina Barone, Social Science MPhil/PhD

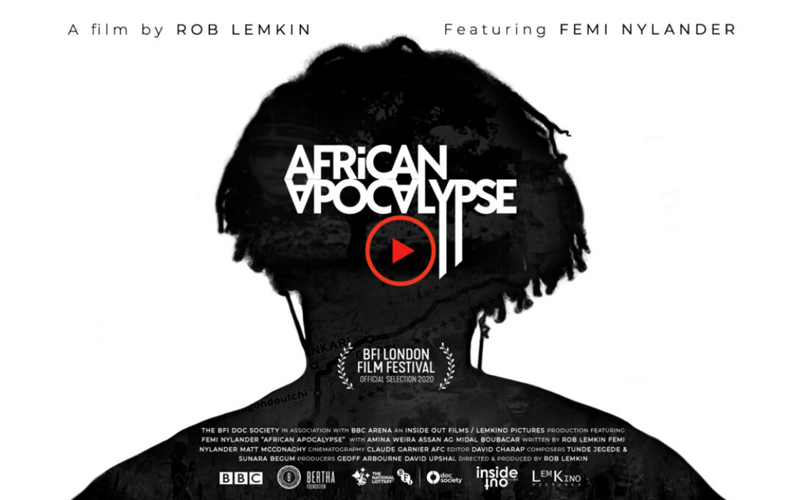

‘This film is about ghosts. Ghosts of the past that even while they slumbered have continued to influence the present’ wrote Rob Lemkin, the director of the docu-drama ‘African Apocalypse’ screened at UCL on December 15th 2022. The ghosts are those of the victims of the 1899 French mission in what is now Niger, the uncountable men, women, and children brutally assassinated, whose obliteration broke the continuity with the ancestors and whose pain still troubles their descendants. But those ghosts are also the spectres of the perpetrators’ evil conscience, the ruthless inhumanity at the core of the so-called civilising mission of colonialism.

At the turn of the 20th century, in the full heist of Europe’s ‘scramble for Africa’, such civilising mission translated into numerous exploratory expeditions. Under the alleged goal of mapping unknown spaces, colonial powers funded military contingents that occupied land, destroyed villages, local chiefdoms and kingdoms, ultimately installing full colonial domination in-land. The ‘discoveries’ of celebrated explorers like Brazza (French) and Stanley (British), who roamed the river Nile, Congo and its affluent Ubangi, were functional to the expansion of the then French and Belgian Congo (equivalent to nowadays Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and Democratic Republic of Congo). This established a colonial model of exploitation that Robert E. Park, the future co-founder of the Chicago school, called vampire-like in his Congo papers (1904-1907). In the race to contain English expansion in Sudan, between 1899 and 1900 France carried out three missions (called after their commanders, namely Voulet-Chanoine, Foureau-Chami, and Gentil) that, starting from what is now Senegal, Algeria and the Republic of Congo respectively, would eventually converge in the Lake Chad sowing death and destruction along the way.

‘African Apocalypse’ is about the first of those missions. Poet-activist Femi Nylander, who is the film’s co-author and narrator, follows French commander Paul Voulet’s traces along one of Niger’s national roadways that lies on the colonial mission trail. As he advanced, Voulet unleashed a killing spree that eventually induced France to remove him, which resulted in Voulet’s assassination, but did not stop the military invasion from reaching Lake Chad.

These circumstances echo Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) and Femi Nylander engages with it during his journey. The novella’s unsettling depiction of a descent into horror, demystifying the hypocrisy of self-proclaimed civilisation, is an inescapable reference. Francis Coppola’s 1979 Apocalypse Now (alluded to by the title ‘African Apocalypse’) and Spike Lee’ Da 5 Bloods (2020) transpose Conrad’s story in Vietnam to depict the horrors of US militarism and racism. Director Rob Lemkin was first inspired by Sven Lindqvist’s 1996 book Exterminate All the Brutes, a quote from Conrad, in turn transposed into a 2021 mini-documentary series with the same title by Raoul Peck. Like a game of mirrors, these cross-references expand the perspective on colonial violence, but risk hiding the source, the actual historical events, under the multiplication of artistic depictions.

‘African Apocalypse’ does not fall into this possible trap. It is on-the-road research that combines oral history and archival study with the poignancy of Femi Nylander’s reflections to recreate events with accuracy and humanity. Famously, in 1975, Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe denounced Conrad’s racism for his dehumanising depiction of Africans. This movie does not fall into this trap either. It puts the Nigeriens’ narratives, individually and as communities, at the centre.

People’s memory of the crimes is still fresh. They happened only 120 years ago and many elders report stories listened to directly from the survivors. Unhealed, the pain is passed on. Outside a school, young students relate emotionally their indignation and desire for reparation. Many of the destroyed communities never had any infrastructure built since.

During the post-screening debate, Nigerien cineaste Amina Weira, a film participant (live by Zoom from Niger’s capital Niamey), stressed how current youth migration is highest from the communities that were most affected by colonial violence. To Nigeriens, migrants’ deaths on the trans-Saharan routes are but a tragic legacy of the destitution and forced displacements brought by colonialism. By contrast, European policies’ approach to African migration is vitiated by what Achille Mbembe calls ‘presentism’, namely the omission of the past and the suspension of the future, misreading African social reality from the angle of a short-sighted present.

AbdoulKader Mossi, co-ordinator of the Collective of the Nigerien Diaspora, emphasised the importance of recognising the scars of the past to devise a way forward. Voulet’s mission used to be only briefly alluded to in primary schools, he related, whereas now ‘thanks to the film, this story will never be forgotten’. To contribute to memorialization, ‘African Apocalypse’ has been screened in various locations of Niger, including Abdou Moumouni University of Niamey, stirring national debate. A Hausa translation of the film, made by former BBC Hausa presenter Sulaiman Ibrahim who also attended the panel discussion, was viewed by more than eight million people in Niger and Nigeria in 2022. The director Rob Lemkin plans to bring it to remote rural communities through a caravan during 2023. Esther Stanford-Xosei went further and called for reparation. As executive director Maangamizi Educational Trust and co-founding chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Afrikan Reparations, she envisioned the film as instrumental to prosecute crimes against humanity, within a holistic vision of reparation that include the legal, ethical, and social dimensions.

Some participants in the debate also touched on more intimate, soul-searching, issues. Being of African descent, they shared the dilemmas of reinterpreting and passing on the wounded richness of their African heritage. This echoed Femi Nylander’s own musing in the film. Himself British-Nigerian, he reassessed his position as a black Brit through his encounters with Nigeriens, and witnessed the resilience of their spiritual worldview, as well as their need for reparation.

This brings forth the promise and task hidden in the title of the film: that an African apocalypse may not only be the revelation of the crimes of the past, but also the beginning of a new era made possible by reckoning and mending the wounds of Europe’s and Africa’s shared history. This UCL event, allowing students and social actors to discuss together past and present societal injustice, is a much-needed step in the long journey toward personal and collective healing and reparation.

The event received the support of UCL Arts and Humanities Faculty, the Sarah Parker Remond Centre, the Social Research Institute, the Migration Research Unit, and UCL’s Grand Challenges.

Close

Close