Untangling the teenage brain

By Clare S Ryan, on 15 September 2011

Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore is a cognitive neuroscientist who researches something many of us find mysterious – the teenage brain. She believes that our adolescent years are a period of great change in terms of brain activity and being able to untangle what is going on could have wide-ranging implications for education. I went along to her lecture at the British Science Festival to find out more.

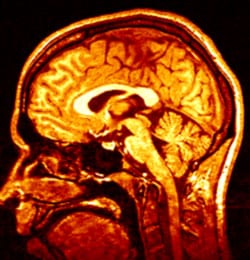

A newborn baby has nearly the same number of brain cells as an adult, an astounding 100 billion. The difference, as you might already know, are the connections between the nerve cells, or neurons, which change massively over the course of a person’s life.

A newborn baby has nearly the same number of brain cells as an adult, an astounding 100 billion. The difference, as you might already know, are the connections between the nerve cells, or neurons, which change massively over the course of a person’s life.

By six months old, a baby’s brain is filled with so many connections that they actually have to be reduced to adult levels. Brilliantly referred to as ‘synaptic pruning’ (it’s a bit like trimming an unwieldy shrub of intertwined neuronal branches), the process leaves the brain with the connections that it uses the most in its particular environment.

This explosion of connections, followed by a bit of pruning, has led to the common misconception, according to Professor Blakemore, that the first three years of a human’s life are the most important in terms of brain development. Not so. She explained how most studies of brain development have been done on animals, specifically monkeys. By the age of three, monkeys are sexually-adult animals. As we know, this is not the case in humans who have a much longer period of childhood and adolescence.

Professor Blakemore’s work has focused on what is happening in the brain in this extended period of development around puberty – especially in a part of the brain called the pre-frontal cortex. It’s this area that is responsible for higher functions, such as planning, self-awareness, theory of mind and introspection, which makes us different from all other animals.

Research from the Blakemore Lab has shown that the balance of grey and white matter changes during adolescence and that activity in the pre-frontal cortex actually decreases between adolescence and adulthood.

But what does this mean for the education of teenagers? One audience member asked Professor Blakemore the great question, “If you were a headmistress of a free school, what would you do to improve education?” After a bit of thought, she said that early indications were that changing the timings of the school day to start at 10am (to fit in with teenagers’ changing circadian rhythms) and giving extended lessons in time management to GCSE students worked well in improving results.

Research on the teenage brain is a surprisingly young science, perhaps only 10 years or so old. However, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that this kind of research is invaluable in improving education, and may even be able to help with wider societal problems such as rioting, dangerous driving and the onset of mental health disorders.

Close

Close