What do women who are overdue for cervical screening know about the risk factors for cancer?

By Jo Waller, on 21 May 2019

Authors: Mairead Ryan, Laura Marlow and Jo Waller

Attending cervical screening between 25-64 years (every 3 or 5 years depending on age) means abnormal cells on the cervix can be picked up and treated before they develop into cancer. In the UK, about 3,100 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer each year and 850 die of the disease. This number could be reduced if more women were up-to-date with screening, but the proportion of women who are overdue for screening is increasing every year, across all age groups.

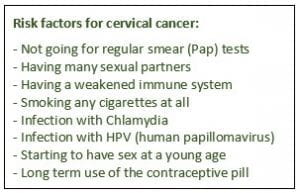

To make an informed choice about participation in screening, it’s important that women understand the things that increase their chances of developing cervical cancer. In particular, they need to know that their risk is higher if they don’t go for screening. In our study, just published in Preventive Medicine , we surveyed women aged 25-64 (793 participants) who were either i) overdue for screening or ii) did not intend to go for screening when next invited. The aim of the study was to assess whether women who decline screening are making this decision based on a good understanding of cervical cancer risk factors. We asked women to say whether they thought that certain risk factors could increase a woman’s chance of developing cervical cancer. All eight risk factors that we showed are known to increase cervical cancer risk, so women with good knowledge should have selected them all.

We found that many women had low awareness. Only just over half (57%) of the participants recognised that ‘not going for regular smear (Pap) tests’ may increase a woman’s chance of developing cervical cancer and far fewer recognised ‘infection with HPV’ as a risk factor (29%). We also found that women from non-white ethnic backgrounds were less aware that not going for regular screening could increase their risk of cervical cancer, compared with white British/Irish women.

These findings suggest that many women are not making informed choices about screening. All women included in our survey should have been sent educational leaflets about cervical screening, but as our previous research in bowel screening shows, women may not be reading these or remembering their content. Further public health action is needed to explore effective communication methods, including non-leaflet approaches, to ensure that all women are making an informed decision about cervical screening (non-)participation.

Close

Close