How does testing HPV positive make women feel about sex and relationships?

By rmjlkfb, on 21 August 2019

A previous blog described how a new way of looking at cervical screening samples called primary HPV testing is being introduced into the NHS Cervical Screening Programme. In this post, we will describe the results from our recently published review which looked at whether testing HPV positive has an impact on how women feel about sex and relationships.

Why might testing HPV positive have an impact on sex and relationships?

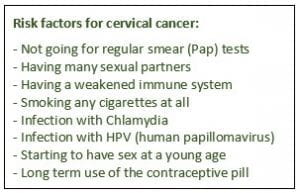

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a very common sexually transmitted infection (STI). It’s so common that most men and women will be infected with HPV at some point in their life, often without them knowing. Because of the sexually transmitted nature of HPV and with the introduction of HPV primary testing in England, we wanted to find out whether testing HPV positive could have an impact on sex and relationships. We reviewed all previous research that has explored the impact of an HPV positive result on sex and relationships among women.

What did we find?

There were 12 quantitative studies, which used surveys to collect data on a range of different outcomes such as sexual satisfaction, frequency of sex, interest in sex and feelings about partners and relationships. The results from these studies were very mixed with some studies suggesting that testing HPV positive did have an impact on sex and relationships and others suggesting that it didn’t.

Three main themes emerged from the 13 qualitative studies, which mainly used interviews to collect data:

- Source of HPV infection – women were concerned about where the infection came from and whether it came from a current or previous partner. Some expressed concerns that their partner had been unfaithful and wondered whether that was how they had acquired HPV.

- Transmission of HPV – concerns about passing on HPV to a partner were common. Some women were also worried about infecting their partner and their partner re-infecting them, not allowing the virus to be cleared and increasing the risk of cervical cancer.

- Impact of HPV on sex and relationships – Some women reported a reduced interest in and frequency of sex following HPV. HPV had a negative impact on some women’s sexual self-image. The risks associated with oral sex were mentioned by a few women who were concerned about passing HPV on to their partners in this way.

What do our findings mean?

It is possible that testing HPV positive may have an impact on sex and relationships for some women, however the extent of this is unclear. As none of the studies included in the review were in the context of primary HPV testing, this work highlights the need for further research in this context. As primary HPV testing is introduced more widely, it is important to understand the impact of an HPV positive result on sex and relationships to ensure that this does not cause unnecessary concern for women.

Close

Close