I don’t need cervical screening anymore – or do I?

By Laura Marlow, on 9 August 2019

By Laura Marlow, Mairead Ryan and Jo Waller.

Having cervical screening (smear tests) when you are older is just as important as when you’re younger, yet many women aged 50-64 years do not attend when invited. One reason older women decide not to attend anymore is because screening can become more uncomfortable after the menopause. We previously explored the potential for doing screening without a speculum as an alternative for these women. Another reason that some older women give for not attending their screens, is that they no longer feel it is relevant for them because they are no longer sexually active or have had the same partner for a long time.

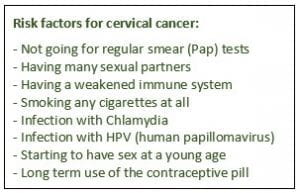

Cervical cancer is caused by HPV, an infection which is passed on through sexual contact. But it can take a long time for HPV to develop into cervical cancer, so past rather than current sexual behaviour is what’s important. For an older woman, HPV can be the result of an infection acquired many years ago. In our latest study, published this week in Sexually Transmitted Infections, we wanted to see if explaining this long timeline between acquiring HPV and developing cervical cancer could help to increase the extent to which older women saw screening as relevant to them.

We recruited women aged 50-64 years who said they would not go for screening again and asked them to read some information about HPV. We then looked at changes in their perceptions of cervical cancer risk and intention to go for screening. All women read basic information about HPV but some of the women also read the statement:

“Women aged 50-64 should be aware that HPV can take a long time to develop into cancer (10-30 years). This means that even if you have not been sexually active for a long time or have only had one partner for a long time, you could still be at risk of cervical cancer”

Women who read this additional information were more likely to increase their perceived risk of cervical cancer and to increase their intentions to attend when next invited. In the group who read this information a quarter of women increased their intentions to be screened compared with just 9% of the control group (who only read basic information about HPV). While this study is experimental, and measured intention to go for screening (not actual behaviour), it suggests that explaining the long time interval between getting HPV and developing cervical cancer may be a useful way to increase cervical screening intentions in those who do not plan to attend.

Close

Close