Downsize homes to downsize energy consumption

By ucftgmh, on 19 March 2015

When we hear the words “housing crisis”, the first thing that comes to mind is the exorbitant prices for houses, in particular in London and the South East. And quite frankly, after only two months of house hunting in Cambridge, I am fed up with manipulative estate agents, and competing against dozens of other bidders. Housing is just not affordable for a large part of the young generation, and in particular, the social housing sector sees a lack of adequate properties.

When we hear the words “housing crisis”, the first thing that comes to mind is the exorbitant prices for houses, in particular in London and the South East. And quite frankly, after only two months of house hunting in Cambridge, I am fed up with manipulative estate agents, and competing against dozens of other bidders. Housing is just not affordable for a large part of the young generation, and in particular, the social housing sector sees a lack of adequate properties.

Those of us working in the energy field might have a second strong association with the words ‘housing crisis’, and that is the poor quality of the English housing stock which is associated with energy consumption that is higher than it would need to be if properties had better insulation, newer heating systems, and more double-glazing. In particular, in the privately rented sector, houses are often in a poor condition.

Lately, I have been wondering if there is an aspect of the housing situation which could mitigate the scarcity of (appropriate) properties, and even have an impact on energy consumption – and that is if people downsized to a smaller dwelling. In all recent analysis that I have done, building size is the strongest predictor of domestic energy consumption: the larger a property, the more energy is consumed. The effect of building size is stronger than the effect of number of people in the household.

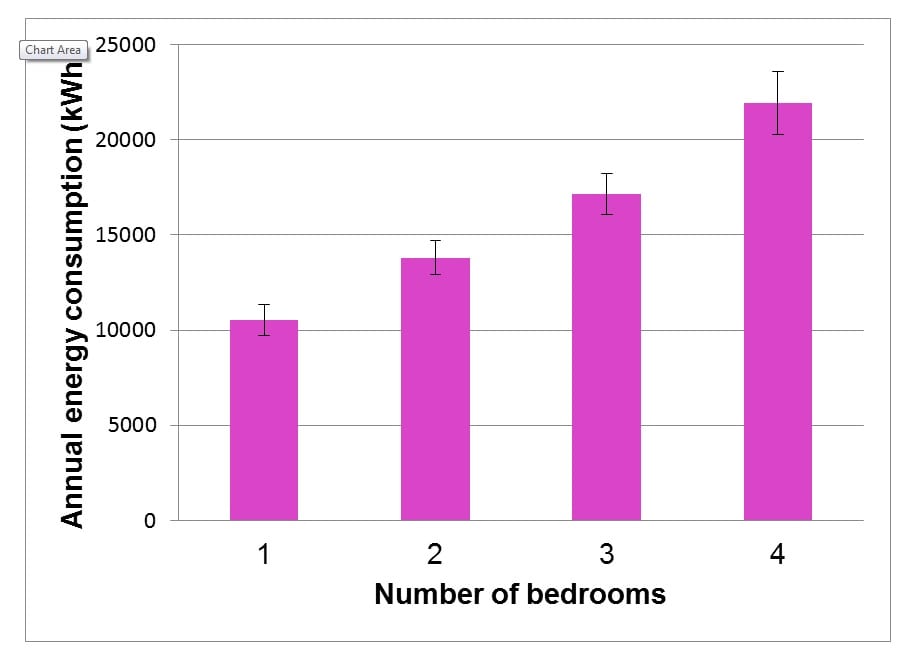

The figure below exemplifies this effect (data taken from the Energy Follow-Up Survey and the English Housing Survey): It shows average energy consumption for a single person-household with various numbers of bedrooms. Whilst this is of course a very simple analysis, it shows the basic effects – the more bedrooms, the more energy is consumed.

The Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG, 2013) reports that around 8 million households were estimated to be under-occupying their accommodation in 2011-12, i.e., they had at least two bedrooms more than they needed according to the bedroom standard. That is about one-third of all households!

The overcrowding rates are significantly lower and were estimated to be about 3-5%. Even though London sees overcrowding in 11% of households, 21% of homes have two bedrooms more than needed and 28% one bedroom more than needed (ONS, 2014). The bedroom standard sets out rather minimum criteria: A separate bedroom is allowed for each married or cohabiting couple, any other person aged 21 or over, each pair of adolescents aged 10-20 of the same sex and each pair of children under 10.

I really don’t begrudge anyone wanting to have another bedroom beyond these criteria. But if we could redistribute only that part of housing where current occupants have two or more spare bedrooms – across owner-occupied, privately-, and socially rented sectors – we could mitigate the housing crisis. There would be more properties on the market, prices would hopefully drop, and we would see more people living in adequately sized dwelling; with a positive impact on energy consumption.

One scheme that basically enforces downsizing has received lots of – negative – attention: the “bedroom tax” whereby social housing tenants lose a share of their entitled benefits for occupying more bedrooms than deemed necessary. Of course, such a scheme can only work if appropriate alternative housing can be provided, if everyone affected could move to an alternative property close by – but exactly that has apparently not been the case, and then the bedroom tax is more an unjust penalty. In general, the amount of under-occupying is rather low in the social housing sector; it is by far highest amongst owner-occupiers so much greater impact could be achieved if targeting this sector of the population.

Assuming there are suitable properties, downsizing has not only advantages for others on the market but also for those who downsize: lower bills, less maintenance work, potentially more age-appropriate housing, freed up capital for owner-occupiers, less rent, etc. Houses could be turned into flats for those who want to stay where they are. Taking a lodger could be an idea – schemes exist where students or apprentices live for hardly any money in the household with an older person but help out with chores, keep the owners company, etc. Also, a pilot scheme was designed in London, the Redbridge “Free Space” project in which property owners leave their house to move to a smaller, more age-appropriate housing, but retain ownership of their house. The dwelling is rented out by the Council who takes care of all landlord responsibilities but the rent incomes goes to the owner.

Some survey data indicates significant interest in downsizing – how can we ensure that this interest is turned into action to help reduce (unnecessary) energy consumption and impact positively on the housing market?

References:

DCLG (2013). English Housing Survey – Headline Report 2011/12. Accessed 12.03.2015

ONS (2014). Overcrowding and Under-occupation in England and Wales. Accessed 12.03.2015.

Close

Close