Facebook as freedom

By Jolynna Sinanan, on 13 October 2013

We started this project by thinking about Facebook as an ‘in’ to understanding the social totality of people’s lives. Facebook may be the means, but relationships are the ends. One of the themes that has emerged from Trinidad is how people navigate relationships that are given, for example kinship, family and the community where one grew up in a small town where most people know each other and relationships that are made such as friendships through school, university, work and interest groups.

In other blog posts, I have mentioned aspects of ‘Trinidadian’ uses of Facebook, to ‘fas’ or ‘maco’ (look into) other people’s business and existing through visibility is a major theme of Danny Miller’s Tales from Facebook. To take this further, Facebook could also tap into another Trinidadian theme, that of freedom. Within family relationships for example, bound by obligation and reciprocity, while people value being dutiful to their families, there may be an underlying resentment about being taken for granted.

On Facebook, where one’s social circles collide and congregate in the same space, a person may be friends with most people they have known face-to -face for several years, but it may be the only space where they exist as an individual. My pre-theorising of this comes from two examples from El Mirador. Two ‘hubs’, or clusters of people that I have gotten to know are an Evangelical community church and a group of sales people from the international multi-level marketing company Amway. Both groups strongly emphasise belonging to a community, the church has its usual service on a Sunday morning and Amway business owners have monthly meetings and in the times in between, when the entire group doesn’t get together, members take to Facebook. People in both groups tag each other in events, and individuals post regularly in relation to the interests of the group. Church members post a Bible verse that they know is relevant to another member or one they feel speaks to their situation of the week or an inspirational quote or meme. Amway members post similarly, with motivational quotes of images that encourage their fellow members with their sales and businesses.

A quick look at the timelines of some members of these groups and I can see they are no less active in the lives of their family and friends, multiple people post or comment, the individuals are tagged in non-church or non-Amway activities, but the difference is that the majority of post by the profile owner reflects their independent affiliations and interests, as if to assert “I may be all these different things to different people, but this is me.”

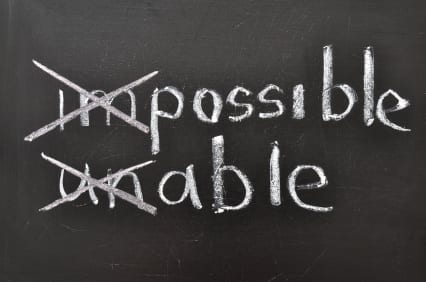

Social media may be a huge source of entertainment or ways to pass the time for vast amounts of people in different contexts such as people on long commutes or shop sellers in the small stalls, but for people who have grown up in less populated places, where they are less anonymous, Facebook might be a ticket to individual freedom.

Close

Close