JoiHok!: New UCL graduate sets up TB initiative in Kolkata

By rekgngs, on 30 March 2020

I met Sreyashi Basu in mid-January this year. She’d dropped in to say hello to Prof Tim McHugh, who’d been a project supervisor during her UCL BSc course, which had finished the previous summer.

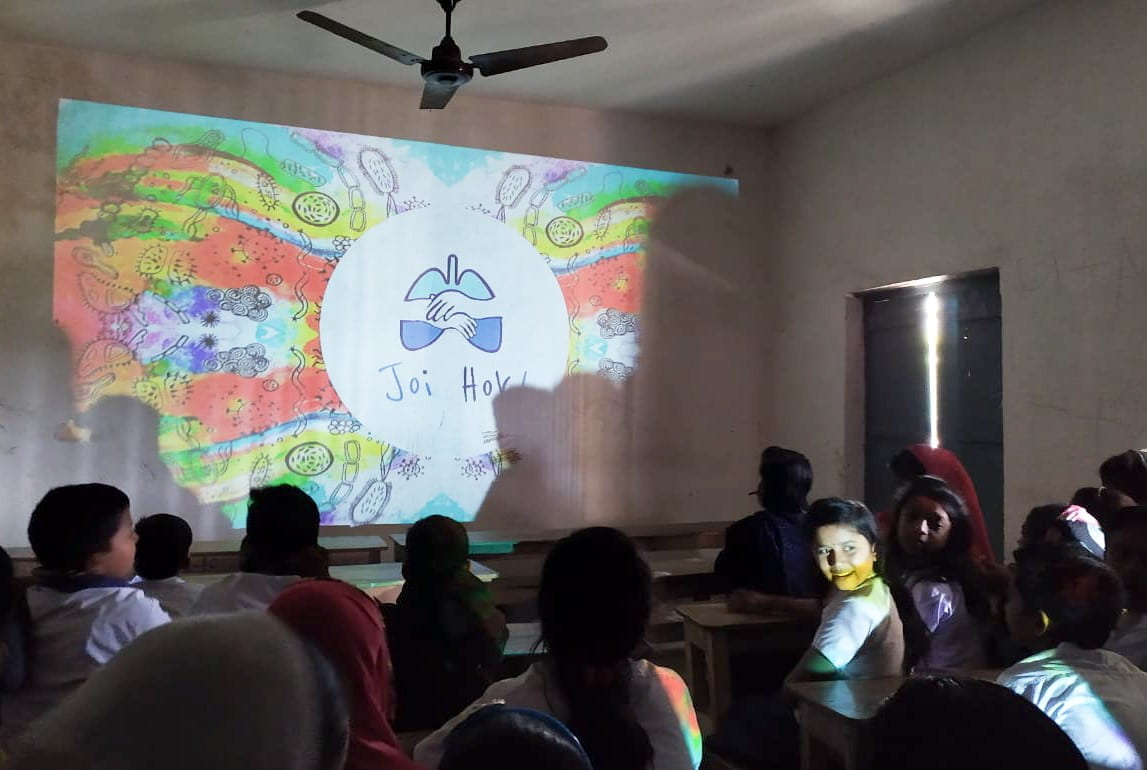

I was amazed at how she had spent the six months after graduating setting up a TB initiative in Kolkata from scratch, coming up with an original idea, and working with laboratory scientists, local artists, charities, and schools to engage children and communities with information about TB. She’d also designed materials, produced videos and set up a website.

I was keen to know more, and over email, Sreyashi told me about herself, and about her project, Joi Hok! (which means “Let victory be yours!”).

You graduated in summer 2019 from UCL – tell me about yourself, how you came to study at UCL, and what you did here

My name is Sreyashi, though my nickname is Koyel – which is what my friends, family and most of my professors know me as. I was born and brought up in the UK till the age of 8 after which I relocated to India with my family. I moved to Kolkata, the capital city of West Bengal.

It was in Year 7 at school, when I first learnt about bacteria, and microbiology in general. I was already vaguely acquainted with microbes seeing as I used to read medical thrillers at an early age, particularly those to do with biowarfare conspiracies. I still remember how my biology text book looked, and how Tuberculosis was dedicated a full 3 pages of description, whereas other diseases were given an explanation of merely 3 lines! It was as if I was learning everything there was to know about TB – but of course I could not be more wrong.

After completing my high school studies, I decided to apply to UCL to pursue a Bachelors in Biomedical Sciences. I didn’t have the slightest idea what career path I wanted to choose yet – just that I loved learning about microscopic bugs!

During my second year at university, I started thinking about lab placements to do in the summer. After emailing around in attempt to find an internship related to TB, I was eventually rewarded the opportunity to work with Prof. Timothy McHugh at the Royal Free Hospital. In his lab, I investigated the susceptibility of Mycobacterium bovis (known for causing bovine TB) to different first line drugs, including isoniazid and rifampicin. This internship was my first glimpse of what working long term in a research laboratory was like.

Following this, I felt motivated to do my final year dissertation in a TB research lab as well. At the time, my project supervisor was investigating a novel animal model of infection – the zebrafish – to study the pathogenesis of Mycobacterium marinum, which I found immensely fascinating. Though I settled on working with Streptococcus pneumoniae for my project due to time constraints, working alongside postdocs in the lab who were researching on TB and listening to their experimental findings at lab meetings was all in all a truly rewarding experience.

While growing up, were you aware of TB or infectious diseases in general?

As a student growing up in an international school, “bacteria” and “viruses” became mandatory chapters in our biology text books from year 8 onwards. I had vaguely heard of cholera, AIDS and TB but never in great depth. The mention of dengue and malaria would habitually pop up in the local newspaper but I did not take a real notice to TB until A levels began.

My method of learning consisted of mainly sketching microscopic diagrams of bacteria. I became obsessed to pursue a career in microbiology if it meant that I could stare at miniscule creatures down a microscope all day!

Towards the end of high school, my father – a gynaecologist – asked me to assist with the literature research for a paper he and his team were writing. The paper was a case study which looked at the efficacy of TB-PCR for diagnosing genital TB in women. I learnt a lot from this experience, particularly the fact that TB affected other parts of the body and not only the lungs.

After your degree, what happened – and how did you end up getting involved in TB?

I did my final year thesis in a lab where zebrafish were being investigated as an animal infection model for TB. It was not a surprise that I loved my project considering I’m a Bengali and Bengalis are notorious for being obsessed with fish!

When I explained my project to my friends, I started to think about ways I could communicate the research in a more interesting way perhaps through art. Before I knew it, I was sketching the anatomy of a zebrafish in the style of patachitra – a type of folk art from Bengal. As a child, we were introduced to a group of artists performing patachitra in our school and we participated in an interactive workshop with them where we painted on walls and sang their music.

I decided that I wanted to convey current TB research to the public – specifically through this art. To do this, I brainstormed ways I could go about the process of communication. More importantly I had to recognise my target audience. Seeing as West Bengal is my home, I decided to return back for a brief period and start an initiative that would engage with the local community.

One of the largest factors that contributes to TB cases in India is the stigmatization and social attitudes of the community towards the disease. These issues persist in rural areas, particularly where people lack education and medical resources. If we are to change people’s perception of the disease, we need to first describe what exactly TB is and why drug resistance is such a big problem.

So, you set up a TB initiative – did you have any experience of this sort of thing? How did you know – or decide – what to do?

JoiHok! is a project that started out as a solo effort – though later on in the year we managed to secure a long-term collaboration with a UK-based laboratory.

Personally, I’ve never had experience with setting up a new initiative from scratch. Yet with a little help from my parents who are established entrepreneurs in their field – I recognised that the first thing I had to do was to start branding Joi Hok! – through creating a logo , setting up a website and publishing relevant social media content.

I then went on to contact the skilled artists who practised patachitra, and spent lengthy hours travelling to and from their village in Mednipur. I spent an entire day with them learning about their rural background and how they sang whilst presenting their art. After explaining my initiative to one of the artists in particular, Swarna Chitrakar, she agreed to create a painting about TB.

Contacting the puppet play team and transporting cameramen to the puppet theatre in Ranaghat (53 miles from Kolkata) was quite a strenuous process. Eventually we managed to create a professional video of the entire puppet play which was then ready to be shown to the public. After careful planning and workshop design, I began conducting the workshops in schools from the beginning of November last year.

What difficulties did you face?

As a leader of the initiative, I found it difficult to assemble and materialise my ideas at first. Yet after a few workshops, I became better and better at managing the flow of events and dealing with unexpected hurdles in a pragmatic way.

It was also not easy convincing teachers to allow our workshop as some institutions were particularly worried that the campaign would interfere with children’s study time and exam preparation. So, I got in touch with local NGO schools, who seemed to be more open-minded, and decided to perform awareness programs with their classes first. In December, our activities started to gain attention from the local press and several articles on our workshops have been published since.

You mentioned a collaboration?

Yes, one connection I made was during my visit to the Mycobacteria Research Laboratory at Birkbeck, University of London to meet Professor Sanjib Bhakta, who also happens to be one our family friends. Professor Bhakta suggested that it would prove fruitful to provide the community with an up-close view of the kind of ground-breaking research that forms the backbone of anti-TB drug discovery and development. Through relaying their laboratory research, which highlights antibiotic action and host-pathogen interaction, we could disseminate evidence-based knowledge about the development of antibiotic resistance and its spread in a high TB-burden setting.

To explore how this JoiHok! collaboration could bridge the gap between lab science and public health research, we had a meeting and a tour of the mycobacteria research laboratory at Birkbeck. In further meetings, we brainstormed ideas and came up with a way to incorporate key concepts of drug discovery and antibiotic resistance in addition to the basic TB facts that were being introduced to the children in the workshops.

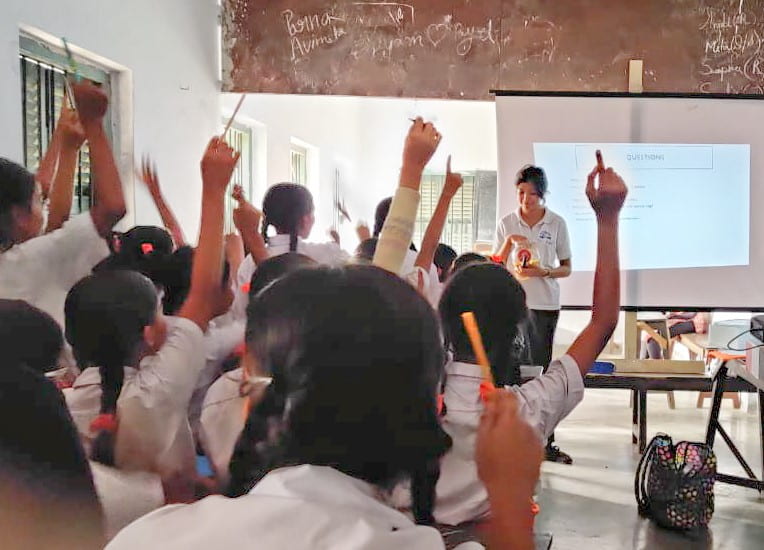

It was then decided that Professor Bhakta would attend and participate in a workshop during his visit to India. This event would be an extended version of our daily workshops, with an added panel discussion inclusive of the students. Young specialists from the field of scientific policy, medicine and pharmacy would be invited to debate on issues surrounding antimicrobial resistance and interact with the students. A patachitra style drawing competition (on a chosen topic of AMR) would be held, and a song-writing workshop to follow. We anticipate that by holding this kind of workshop, we might encourage teenagers to take an active interest in the impact of scientific research on our lives, and nurture an early career interest in laboratory sciences. This collaboration brings a case in point that by taking more proactive role in public engagement, working professionals in the field can directly contribute to preventing and managing TB beyond the confines of the lab.

What comes next for you?

Though this project has truly been an eye-opening experience for me, I’ve realised that I need to enrich my background knowledge in the area of public health. As a result, I’ve taken up an offer to do an MSc at the LSHTM beginning September 2020. Many people questioned my decision to take a gap year to pursue this dream project instead of applying for a masters degree straight after University. One thing I have learnt so far is that with new experiences, people change and so do ambitions. If I had pursued a masters first, my determination to carry out this campaign might have dissolved and I would have lost out on the opportunity to initiate something new and exciting from scratch.

What will happen to Joi Hok!?

I initiated the project “Joi Hok!” with an outreach target of 50 schools in mind, corresponding to ~2000 children. In the long term, I would have liked to continue Joi Hok! workshops in more schools and gather additional data had I not felt the urge to go back to academia to enhance my background knowledge in the field. My primary motive for Joi Hok! was to be the example to our nation, that educating someone does not necessarily come hand in hand with being proficient in reading and writing. We find that many children below the poverty line, despite attending public schools, do not know how to write a correct sentence in their native language. Seeing how illiteracy and a lack of will to educate form the root of many problems in India, we need to innovate new ways through which we can engage the public and motivate them to be the change that India needs to see. This is where art and music come in. We should look towards forming new collaborations between art and science for the purpose of advocating not only TB, but other diseases like HIV, measles, diptheria, cholera etc. which put the public health at a serious risk.

What do you think are the most important things you’ve learned from your time at UCL, and working on and with Joi Hok?

At university, I definitely recognised the importance of attending conferences and networking events. Throughout my degree course, and particularly my last year at uni I knew what I enjoyed learning about, but I just didn’t know if these interests coincided with my professional goals as well. Meeting and talking to research scientists, laboratory artists-in-residence, policy makers, science ambassadors, health-tech specialists and learning of how they progressed through various stages of their life to reach where they were today was truly fascinating. I was continuously encouraged when I spoke out about my desire to switch to global health and make an impact in a public domain. I just loved everything about sharing knowledge and interacting with passionate individuals from different backgrounds. It’s not a surprise that I decided to take a year out to pursue scientific engagement!

With Joi Hok!, I learnt that with a new initiative, one cannot expect a perfect response every single time. In some of the workshops, a few students didn’t interact at all or gave incorrect answers. At the outset I felt like I had failed them. Yet I eventually realised that there would always be anomalies. Not everyone will always listen or be interested. This “lack of care” also applied to a few of the adults I had talked to as well, particularly headteachers who denied the implementation of our program at their schools because they were worried that this would cause a disruption of valuable study time. They just couldn’t understand the need to raise awareness of a “common man” disease like TB. Then there were other teachers who appeared interested at first but later refused to coordinate, making the whole process of following up school visits time consuming and very frustrating. The key to tackling these obstacles is to stay resilient, and persevere no matter what. I chose not to lose faith in my cause and stuck to making a difference with the ones that were open-minded and wanted to learn.

Can you think of one moment that was special or fun or inspiring to you in each of these two places?

At UCL, the end of year Infection and Immunity symposium was one of the most memorable experiences I’ve had at university. Everyone in our group gave a small talk on their research project and we attended a drinks reception afterwards where we sang a farewell song to our course director. It was a bittersweet day – I felt so much love for all my classmates and especially grateful for having such an enjoyable time working on my lab project. Though I knew I had accomplished my final year at UCL, I didn’t feel ready to leave this new family I had made so soon.

With Joi Hok!, in one boys’ high school, the children were so involved with our campaign that they were pleading us to stay and keep talking with them. Sometimes I wonder if this was because they didn’t want to go back to their classes, but I appreciated their naive enthusiasm. We ended up staying and sharing stories with the kids for a whole extra hour! They told me to sing a few English songs and even the song we made on TB, again! After that a little boy showed off his dancing skills to some Bollywood music and we wrapped up with a crazy group photo.

I also remember once while evaluating the pre-survey questionnaires of a campaign – one child had written “LG, Samsung, Zebronics” as examples of things they knew about TB already. My volunteers and I didn’t immediately realise but the poor fellow had obviously become very confused and mistaken TB for TV, and had decided to list a bunch of television companies!

Though quite amusing at first, we were thankful to know that the same child had put down a decent answer in the post survey questionnaire that was distributed afterwards.

What do you do outside of work and study?

I love everything to do with music and art (as you can guess from the project itself)! I’ve grown up singing and playing the piano from a young age and when opportunity would grab me I’d find myself scribbling down lyrics or exploring a combination of melodies on the piano. Recently however, I’ve become obsessed with designing graphics. As a devoted subscriber to the well-known magazine Scientific American, I have always been in awe of the illustrations which complement the articles in a very illuminating way. My urge to try something similar of my own led me to digitally design the card game we have introduced into the workshops. Taking into account the difference in standards between my amateur designs and the magazine illustrations, I am taking a few online courses alongside JoiHok! so that hopefully if and when I master Adobe illustrator, I’ll be able to convey my own sci-art ideas in a more organised and attractive way!

Is there anything else you’d like to say / any other questions I should have asked?

I just wanted to say that starting something from scratch is never easy and I experienced a fair share of self-doubt at the outset. I’d often find myself hitting the brick wall of resistance for any change, yet eventually I built enough resilience and perseverance to push me through. Things may take longer than usual, people may fail to cooperate yet despite these obstacles one should never underestimate their true purpose or give up.

“This kind of programme is really important for the children definitely, but will reach people belonging to neighbouring villages who are illiterate or poor. When TB is seen in poor people, they don’t know how to access treatment because they don’t know what the disease is or what it’s about. Whether they are in the hospital or at home, they need to be aware of what exactly TB is.” – Swarna Chitrakar (Patachitra artist)

“My grandmother, uncle and aunt all had TB but now they are fine. We weren’t taught about TB in depth, but after the workshop today we learnt a lot of things about the disease. I always thought TB was caused by a virus!” – Sagar Roy– 13 year old at one of our campaigns (Disha Foundation)

For more information see the Joi Hok! website

- Video about Joi Hok! for World TB Day 2020

- Blog by Sreyashi for the Microbiology Society, for which she had acted as a Champion

- Visit Sreyashi’s YouTube channel

- Visit the Joi Hok! Instagram page

Close

Close