The Astronomer behind the Bar

By Paul F Ranford, on 11 December 2018

Letters of a teenage astronomer provide a story worth telling, and insight into the charm and generosity of the great Victorian scientist, Sir George Gabriel Stokes, Bart., FRS

Not all historical stories are grand, or important in the history of ideas. Not all will appear in the major textbooks, nor in PhD theses. This story will not appear in my thesis, which concerns itself with the development of Victorian science through the biographical lens of Sir George Gabriel Stokes, Bart., FRS, Lucasian Professor, Secretary of the Royal Society, etc etc. Yet, in the course of research, small tales can be discovered and be worth telling, nevertheless.

This little story interests me because it provides evidence that Stokes’ character was unchanging over time and over social strata. It tells us something of his broader, mostly unacclaimed, influence on scientists and thus on the history of Victorian science. But just for once in my researches, Stokes is not the focus. This is, instead, about a boy and young man of whom you have (more than likely) never heard. A boy and young man possessed with a passion for science, and a longing to belong and contribute to an intellectual community far removed from his personal circumstances. It is a story of success and tragedy, closely aligned. That is why this is a story that might be interesting to all, and I feel compelled to tell it.

Let me introduce you to Benjamin John Hopkins. He was born in Haggerston, a suburb in the East End of London, in October 1862. His family circumstances were not comfortable – his mother disabled, his father a carpenter and joiner of no great repute, and later an innkeeper in Hornsey and then Canning Town. The young boy – he had no siblings – was required to work from the age of about 10 in minor jobs around the pub, and in his teenage years, increasingly, as a bartender.

Education was not a universal privilege when Hopkins was young, and he took such teaching as was available to the family (and for which his parents must take credit). His limited schooling kindled in Hopkins a passion for science, and he gained school certificates in science and art. At the age of about 13 his interest in science became a passion for astronomy, and he spent such pennies as he could glean from money provided for food on second-hand books, and (eventually) an old astronomical quadrant. His parents contributed a pocket telescope, and Hopkins spent quiet periods in the pub reading and nights observing. As far as we can tell, he was entirely self-taught in the subject. In late 1876 – so at barely 14 years of age – Hopkins took the extraordinary step of writing directly to Sir Joseph Hooker (then President of the Royal Society) with a theory concerning interactions between light from the sun and a comet’s tail. Hooker passed the letter to Stokes (then longstanding Physical Sciences Secretary of the RS) who replied to Hopkins at length in early November.

There is a constant theme through Stokes’ life. If he saw a scientist who needed help with some work, he provided that help. It is more than interesting to note that this help was afforded as generously to the young “astronomer behind the bar” as to the grandees of Victorian science. But I must not digress to Stokes…

An extended correspondence began. In the 17 years between November 1876 and June 1893, Hopkins wrote 21 letters – some in brief staccato flurries, some after long intervals – to Stokes. (We only have the Hopkins end of the correspondence. The letters from Stokes almost certainly no longer exist, but we can infer much of their content from Hopkins’ enthusiastic responses.)

Hopkins’ writing – a neat cursive script, carefully phrased, a gift to historians that would shame many of the scientists whose wretched handwriting tarnishes the Stokes’ collection – shows few hints of his tender years and lacks nothing in boldness and ambition. With his first response to Stokes (6 November 1876) he encloses his “Hypothesis to account for the tails of comets keeping in a direction from the sun”.

“Please write me an answer, & let me know you have received it alright, also if you think it worth while, reading at the coming meeting of the Royal Society.”

Stokes’ response was immediate (as usual) and clearly encouraging, for Hopkins’ next letter is dated 8th November – only two days after his first. Stokes must have included some detail of John Herschel’s theory of cometary tails, for Hopkins immediately engages with the argument:

“I see by your letter that Sir J. Herschel says, the reason that the tail keeps in a direction from the sun is because [of] the repulsion of similarly charged bodies. What bodies? – Does he mean the small bodies of which the tail is composed (if composed of such)?; or does he mean tail and nucleus? If he means the first question, [it’s] just as likely for the bodies of which the tail is composed, to repel one another towards the sun, as from it, the same with the second question.”

We must, I think, remind ourselves that this is a 14-year-old boy. Yet he challenges assumptions, guards against preconceptions, points out the possible flaws in a theory based upon his own interpretation of the observable consequences. He went on to supply an alternative theory:

“The pressure of sunlight on the earth is (according to Mr Crookes) about 3,000 million of tons, all this power acting in opposition to the force of attraction; therefore, as Comets are of such extreme rarity, light might be the cause (as light has pressure), of the tail keeping in a direction from the sun.”

The radiometer, as an instrument providing evidence of the so-called “repulsion effect” of sunlight, was first demonstrated at the Royal Society by William Crookes in April 1875. Hopkins was up-to-date in his reading.

He admitted to mathematical shortcomings however:

“I have studied Mathematics a little, but not much. I can find the Latitude and Longitude of a place, also find R.A. [right ascension], Declination, & Refraction [caused by the Earth’s atmosphere] in practical astronomy.

Perhaps his mathematics was in fact somewhat in advance of normal for his teenage years. So was his continued boldness – he asked again if his hypothesis:

“…is worth reading before the R.S.”

Clearly Stokes responded immediately and encouragingly enough, for Hopkins next letter is dated 9th November, only the day after his previous. The postal service was better in those days. For the first time he asks Stokes for assistance:

“I should like to know (if you will be so kind as to inform me) if you could get me a situation (if possible) either in the Cambridge or any other Observatory. The reason I ask is, because I have my living to get & I am going to follow Astronomy for it.”

This is ambitious indeed. Astronomy in England in the 1870s was not a highly professionalised calling. The Astronomer Royal and several university and private observatories provided some opportunities for employment. But Hopkins did not have the customary wherewithal – an inherited fortune, a university education and a network of scientific contacts, and preferably all three – to follow his vocation as a paid employee or as a gentleman amateur. He had nevertheless already started to write a book on the subject, reporting to Stokes that:

“…the first bit I wrote was on the ‘Moon’ while the first chapter was entitled ‘Astronomical Phenomena’ and explained the cause of an ‘eclipse of the Moon’…”

While Stokes was absorbing all this at some greater leisure – perhaps he realised that immediate responses would initiate correspondence requiring significant amounts of time when it was possible he had other work to do – Hopkins could not bear to be patient. A week later he chased Stokes for a response.

His call was heard and answered. In December 1876 George Gabriel Stokes, Fellow and Secretary of the Royal Society, Lucasian Professor, etc etc went to visit the astronomer Benjamin John Hopkins (14) at the Dog and Gun pub in Burnham Street, Canning Town.

We don’t know what occurred there. Stokes met Hopkins and his parents (some subsequent letters include a note of their good wishes to Stokes), and presumably the conversation inspired the young astronomer to greater endeavours. On 5th February 1877 he reported:

“…I have erected a Transit Circle, with which I intend to form a catalogue of the stars, and to observe the ☍ [opposition] of ♂︎[ Mars]. I should very much like you to see it… it is made of wood…”

Hopkins also reported on his observations of the sun, on an idea to: “photograph Jupiter’s belts every hour with a view to finding whether there is any law observed by them”, on his calculations of the likely return dates of the two comets, Biela and Encke, and his desire to prove the existence of a “resisting medium”. This last point would certainly have attracted Stokes’ attention, as his theoretical and experimental work on the “luminiferous ether” which – most contemporaries were convinced – permeated all space, had occupied him for several years. Perhaps this had been discussed in the Dog and Gun. Then, in March, Hopkins tells Stokes he is:

“…constructing a polariscope, the case for glasses, as well as the stand, I am making of wood, which will be ornamented.”

This is all rather serious astronomical work for a teenage boy armed with a pocket telescope, an old quadrant and a few second-hand books.

At some stage in 1877, Stokes introduced Hopkins to Lord Lindsay (James Ludovic Lindsay, 26th Earl of Crawford and 9th Earl of Balcarres, FRS, FRAS (1847-1913)), and Lord Lindsay, too, visited the Dog and Gun pub in the August of that year. He must have been impressed; Hopkins was invited to spend a month at the Earl’s estate (and its well-equipped observatory) in Dunecht, near Aberdeen. Hopkins’ joy at such an experience – and his unquenchable passion for astronomy – was reported to Stokes in an undated letter:

“…I have seen, what I never saw before, and I have learnt what I never knew before.

His Lordship is extremely kind, for he not only sent the money for me to go there with, but he also gave me £1 a week while I was there, and [a] 1½-inch Equatorial [telescope] when I left. My mind is still for Astronomy more fervently than before.

I do not know how I shall repay the kindness which you have shown me”

In October 1877 the first discordant note was sounded – Hopkins reported receiving less than encouraging advice from Lord Lindsay’s paid astronomer, who was clearly not possessed of the same magnanimous nature as the two FRS dignitaries. It seems that Hopkins had been recommended to:

“do something else, and only follow Astronomy as an amateur”.

Hopkins asked Stokes:

“…if you would be so kind as to get me another situation in an observatory… I have not given up Astronomy… I do not care what it is I have to do in an Observatory as long as I am in one.

I am 15 years old this month, and I have to do something, but I shall never, never give up Astronomy.”

Even in this slightly unsettled state, Hopkins reported his astronomical work – studying variable stars, particularly Algol [β Persei] and proposed an idea for original research on how the spectra of variable stars change over time. He also suggested a joint venture between the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society to study various unanswered astronomical questions.

Over the subsequent few years, the pace of this extraordinary correspondence lessened. Hopkins attempted to gain paid work, first with a clothmaker (whose business failed) and then with a brass engraver. Stokes was asked to supply references, which presumably was done. In October 1880 (so Hopkins was 18 years old and seemingly more independent) he travelled to Cambridge to visit Stokes, who was unfortunately away from home. The subsequent letter is plaintive:

“…I could not help feeling greatly disappointed, and I really was.”

By this time, Hopkins sought the honour of joining a learned society of astronomers:

“Is any special qualification necessary to become a FRAS… if not, could a person of my position in Society become such?”

Can non-Fellows attend the meetings [of the RAS]?”

But the social cost of Hopkins’ passion was high:

“…none of my friends are of a scientific turn of mind, so that I am only laughed at by them, they [look] on my stargazing as a waste of time.”

At last, in early 1881, Hopkins gained the access to the learned world he craved. An acquaintanceship with the well-known astronomer Cowper Ranyard FRAS (possibly gained in the same way in which Hopkins had forged a long relationship with Stokes) had resulted in an invitation to a meeting of the Astronomical Society, at which:

“…I enjoyed myself immensely… Mr Ranyard has invited me to again attend a meeting…”

Hopkins progressed with the RAS – in January 1883 he had a paper read at the RAS, and on 13th April he was elected a Fellow – the achievement of his dreams. He had several other articles and letters published by the English Mechanic, had papers accepted by the RAS, and was an enthusiastic and frequent contributor of published items in a variety of learned journals, including Nature[1].

Not all stories end with achievement and success, and it is a shame that this story does not reach its fitting end here.

Apart from another letter in May 1883 – Hopkins sent Stokes a gift of a brass engraving of the grand lunar crater “Archimedes” – there is no further contact known until August 1886, by which time Stokes was now President of the Royal Society. Hopkins’ personal finances were never better than unsound. He had married in 1884, and with two young daughters, Hopkins was close to the end of his tether. His employer had gone bankrupt, and in trying to set up a new business on his own account:

“…I had the misfortune to have my wife lose her reason through the worry and anxiety of making both ends meet…”

Looking for work “however humble”, Hopkins still took the opportunity to enclose a paper on “A remarkable sunspot”.

By October, later in the year of 1886, the situation seems dire:

“…as near the workhouse as I ever hope to be… There being no immediate prospect of getting work in my own line, and dreading the hardship I shall experience, makes me write this letter to you; trusting you will pardon me, and hoping you may know of something suitable.

P.S. I do not want to give up the systematic pursuit of science, but if something permanent does not come up I am afraid I shall have to. I did think when I had learnt a trade, I should have been able to have devoted the few leisure hours I get to it, but such is not my fate. I have never allowed my scientific tastes to interfere with the means by which I get my living, and yet it seems as though I am doomed to be crushed beneath the iron heel of poverty.”

We do not know what Stokes made of this, nor if he was able to offer any substantial assistance at all. We do not know if there was any response whatsoever but, if so, there is no reply from Hopkins in the collection. His next letter – November 1887 – merely congratulates Stokes on his election as a Member of Parliament representing Cambridge University.

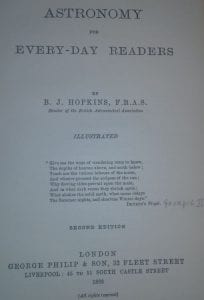

There was then a substantial hiatus in the correspondence. The next letter is dated 6 June 1893, so nearly five years after the last. Hopkins was by then 30 years old. But it seems that contact of some form was maintained, as Hopkins noted a meeting with Stokes in Greenwich Observatory “last Saturday”, and (as apparently promised), sent Stokes a copy of his book Astronomy for the Every-Day Reader. This, astonishingly, is the work first mentioned by the 14-year-old Hopkins in 1876, now completed and published. And at last the sad tale seems to be at an end, for:

“It has met with unexpected success, the 2nd edition (4th thousand) having been called within three months of the publication of the first.”

Hopkins “little book” was a blockbuster. And once again, this would be the perfect place to end, and indeed I wished the story did end here, with success and fortune and surely more sound astronomical work and scientific achievements and perhaps honours to follow.

This was Hopkins’ last letter to Stokes. And with this letter, and the tale of success, comes the sting in the tail, for in the attempt to have his work published:

“I sold the M.S. to Messrs Philips for the nominal sum of £5… Unfortunately I do not benefit by its large sale.

Kindly let me know that you receive it all right.”

£5 in 1893, carefully administered, was probably enough to pay the family bills for a few weeks. Not for very long however, and certainly not the several months that Hopkins had left to him.

For Benjamin John Hopkins FRAS died on 16 January 1894 at the desperately early age of 31, leaving (according to his RAS obituary) “an invalid widow and two little girls in very poor circumstances”.

And so, I’ve written this tragic tale for no reason other than to place on a record – somewhere, anywhere – a remembrance of Benjamin John Hopkins, the “astronomer behind the bar”, a young man with a constant, undiminished, searing passion for science and who was true to his promise to never, never give up Astronomy. Some people are not important, but deserve to be remembered, nevertheless.

[1] See https://www.nature.com/search?q=B.J.Hopkins&order=relevance&date_range=1882-1883

Sources:

Hopkins’ letters in the Stokes collection, Cambridge University Library, Collection: GBR/0012/MS, Add 7656, Reel CM04952

Hopkins B.J. (1893), Astronomy for the Every Day Reader, London, George Philip & Son

Royal Astronomical Society, Report of the Council to the Seventy-fifth Annual General Meeting, pp193-4, Obituary of Benjamin John Hopkins

Close

Close