1/2 idea No. 23: DSAC

By Jon Agar, on 2 August 2021

(I am sharing my possible research ideas, see my tweet here. Most of them remain only 1/2 or 1/4 ideas, so if any of them seem particularly promising or interesting let me know @jon_agar or jonathan.agar@ucl.ac.uk!)

Studying the history of defence research should not be laugh-out-loud funny.

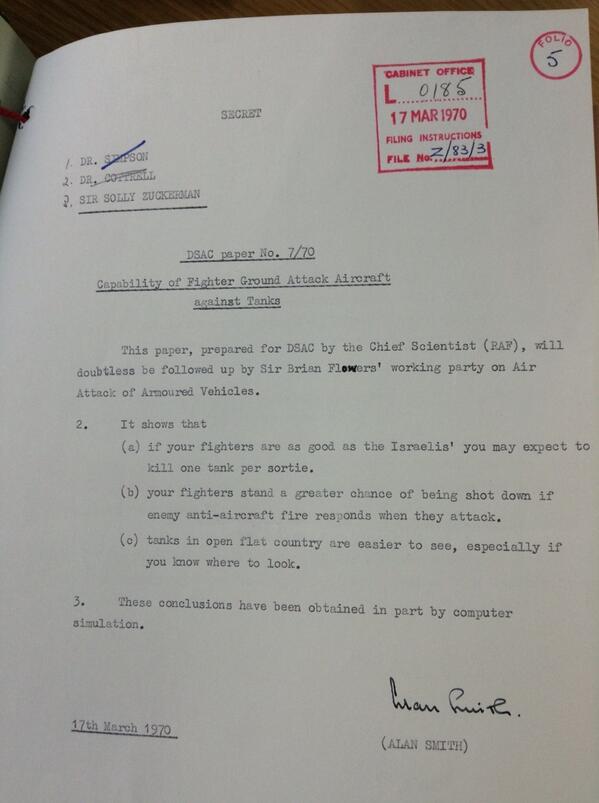

But here (pictured) is a civil servant in 1970 summarising a report on air capability against tanks for the Defence Scientific Advisory Council (DSAC):

“It shows that

(a) if your fighters are as good as the Israel’s you may expect to kill one tank per sortie.

(b) your fighters stand a greater chance of being shot down if enemy anti-aircraft fire responds when they attack.

(c) tanks in open flat country are easier to see, especially of you know where to look.

These conclusions have been obtained in part by computer simulation”.

Alan Smith, wrote this summary, and others, for his manager (Mr Simpson) and the two leading defence science advisers in the UK, Alan Cottrell and Solly Zuckerman, to warn them that a new and elaborate structure for channeling civilian scientific expertise into shaping defence research programmes was foundering.

The Defence Scientific Advisory Council had been established on April Fool’s Day, 1969. Composed ‘principally of scientists and technologists from outside the Ministry of Defence’, it was asked to provide advice, review ‘scientific and technological aspects of the Defence Research Programme’, advise on ‘long-term policy’ including ‘where appropriate… broader aspects of Defence Policy, advise on manpower, scope and balance, bring to attention relevant developments outside defence, and advise on specific issues on request’.[1]

Crucially it was not just a single panel, but sat atop a vast array of sub-committees, including but not limited to:

- Land Warfare Advisory Board

- Biological Research Advisory Board

- Air Warfare Advisory Board

- Maritime Warfare Advisory Board

- Civil Programme Advisory Committee

- Assessments Board

- Hull Committee

- Explosives Committee

- Equipment Planning Committee

- Military Engineering Committee

- Engineering Properties of Materials Committee

- Biology Committee

- Chemistry Committee

- Physics and Engineering Committee

- Weapons and Sensors Committee

- Vehicles Board: Fire Control Committee

- Ships Board

- Machinery Committee

- Applied Biology Committee

- Demolition Techniques Sub-Committee

- Computer Uses Sub-Committee

- Ballistics and Fire Control Committee

- Committee on Operational Research Methodology

- Materials Committee

- Mechanical and Electrical Engineering Committee

- Evaluation and Development Committee

- Committee on the Application of Computer Systems

Even allowing for some renaming over time, that is a considerable number. In 1970, Smith caustically reported that

1. DSAC has bred more boards and sub-boards than anyone can keep track of.

2. Most of these are yapping around the periphery of the MOD without coming to grips with real issues.

3. Some of them are still getting in one another’s way.

Another DSAC meeting was described by Smith as

rambling and inconclusive … in the course of which they raised several thorny and some potentially seditious questions, most of which concern subjects outside their terms of reference … If the Minutes are to be believed, this meeting was in the nature of a collective confessional, and about as constructive.

Yet I think DSAC deserves close historical scrutiny. Each of the committees, boards and sub-committees was filled with scientists most of whom otherwise worked in civilian science. The DSAC system probably represents the largest influx of civilian expertise into the UK defence research system since the Second World War. What did these experts bring, and what did they take away? How were military technologies and techniques shaped by these experts, if at all? Were there consequences for the development of civil science, in academia or industry? How does their work compare to, say, that of the JASONS in the US?

Furthermore the system lasted. Surely an advisory structure has hopeless as Smith portrayed would have been wound up quickly. But the DSAC system continued until 2016, and even then its function was merely reclassified, and was replaced by the similar-sounding Defence Science Expert Committee.

The concentration, and consequences, of British investment in defence research is often overlooked by historians, as David Edgerton has argued many times, not least in The Warfare State (2005). One reason among many for this amnesia is that the archives, born confidential, secret, or top secret, trickle into public view. Brian Balmer and I, when we examined the archives of the Defence Research Policy Committee, which operated from 1947 to 1963, found that commentators on science policy had repeatedly underestimated its significance largely because it had operated discretely and in secret. (I have also studied the DRPC’s successor body, the Defence Research Committee, DRC, up to the late 1960s, and confirmed the effect in a paper published in the collection, Scientific Governance in Britain, 1914-79, edited by Charlotte Sleigh and Don Leggett.)

If we want to understand the factors shaping military science in Britain, and the interdependencies between civil and defence research, then we need a historical account of the DSAC system.

[1] TNA DEFE 10/807. ‘Defence Scientific Advisory Council’, 2 April 1969.

Close

Close