A guest blog from Rosie Beacon, the Centre for Global Youth intern

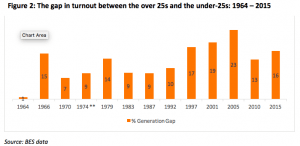

As a politically engaged university student, I have mixed feelings about the general election. In crude terms, the youth voted Labour, the older generations voted Tory. Why? It would be unwise to reduce the exceptional voter turnout to the tuition fees extravaganza. What else could it have been? It is slightly more likely that the youth were more inclined to voting Labour, but what was it that actually pushed them to get up and go to the polling station this time?

Party preferences in the 2017 UK general election by age

It is no secret that social media has become a political campaigning vehicle in its own right. The growth of micro-targeting in electoral campaigns is unprecedented; Labour, in particular, invested heavily in this through ‘Promote’, their own social media micro-targeting wing. Momentum also perfected social outreach through contemporary platforms such as Facebook.

While this was certainly effective, an immense tool which no political party can attempt to control but only to influence, is ‘organic’ social media activity. By organic social media activity, I mean the ways in which people share political material on social media because they are interested in or entertained by the material, not because they have been asked or paid to do so. The term ‘political material’ is now increasingly flexible due to the way that social media has casualised politics, so that ‘organic sharing’ now includes a plethora of political news – it can be funny, it can be informative, it can be incredibly opinionated, or a combination of all of the above.

From my personal experience, it wasn’t the micro-targeting revolution that helped Labour capture the attention of the youth. It was memes, videos, photos, Facebook statuses, and tweets. Jeremy Corbyn was presented on social media as a trend, not a politician. I personally didn’t vote Labour, but I can certainly see why its enticing. Jeremy Corbyn seems like a cool guy and has a cat who features in his Snapchat stories. How likely is it that I know this from reading The Guardian? The fact that he managed to transcend politics and present himself as a person that just happened to be a politician (with ‘hopeful’ policies) is what made him so appealing – a persona he determined for himself and with the help of spin doctors no doubt, but a persona that captured the beady eyes of the social media generation who thrived off it.

The Social Media Generation

Thus the 2017 general election – and the EU referendum for that matter – symbolise a far more endemic trend in the future of youth politics; the social media generation. The formative years of this generation have been characterised by myspace, Bebo, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, Snapchat – sources of socialising but also immediate sources of information.

Would being part of this ‘information generation’ necessarily affect political literacy? Not completely, but social media has certainly provided an innovative platform for those who were already engaged with politics, and it also allows for those that were not necessarily interested to follow it to varying degrees. Whether you want to follow it or not, especially during the general election, it’s highly likely you saw something to do with politics on your timeline once a day. Its mere appearance on our news feeds equates politics and current affairs with off-the-cuff events happening among your friends, not only making it seem casual but this subtly and incrementally builds up an awareness of what’s going on in the seemingly distant world of politics.

But then, on the other hand, couldn’t you just ignore political news if it appears on your timeline? Not everyone follows the Independent and the Times? Crucially, social media has not only created a contemporary platform for politics, but it has fundamentally altered the face of it. It has turned politics into something you wouldn’t necessarily want to scroll past. Politics on social media can be incredibly personal but it can also be lighthearted, humorous and very witty. This could mean anything from reading your friend’s Facebook status debate disputing how corporation tax should be managed or more likely, one of your other friends sharing a video compilation of Joe Biden telling Barack Obama how much he adores him.

Two political memes that have gone viral in the US and the UK

The latter demonstrates how social media has made politics casual and easily digestible, and has exacerbated the trend for ‘personality politics’, which, based on my peer group, Jeremy Corbyn hugely benefitted from. Particularly in the context of the 2017 general election, this is evident in the unforgettable wheat fields trend with Theresa May, heightening her representation as the ‘Maybot’, and further alienating younger voters from someone who looks like just another right wing politician who doesn’t quite ‘get’ the youth. This trend in particular shouldn’t be underestimated – it was massive because ultimately it’s funny and easy to find funny, meaning new audiences could engage with this trend, and thus politics, in a simple way. Social media also allowed for nostalgic photos to be shared of Jeremy Corbyn protesting in the 80s and for videos with Stormzy to become viral, furthering his persona as a man who doesn’t just know the people, he’s another one of the people.

Moreover, it is not just viral videos and memes that build up a political awareness among young people. As we start to make progress with our careers, we are starting to recognise our dependence on political decisions. Now, when young people appreciate how politics affects their adult lives, there is a platform in which they can voice their opinions through status updates and comments on others’ status – a new mechanism of debating and reasoning with other political views that hasn’t always existed. All of these trends are also inevitably heightened against a background of drastic political upheavals, such as Brexit and Trump’s election, which saw young people turning to social media sites as a way of voicing their opinions on these dramatic events.

Is social media a political opportunity or political danger?

In many ways, the general election 2017 crystallized the relationship between social media and politics that has been building for some time. Social media is ultimately invasive (which is why we love it) but this means political personalities are now more important than ever. This is why Corbyn was so successful. Snapchat stories of his cat might not seem like much, but politics has a tendency to dehumanize politicians and he managed to fight against this with the social media generation massively on his side, encouraging a huge and powerful demographic to go out and vote for a man that seemed like he was an actual human being.

However, this social media facet to politics isn’t always a blessing. Social media is a source of misinformation just as much as it is actual information. With such a poor system of compulsory political education in the UK, social media can make voters vulnerable to persuasive views that they’re not well equipped to challenge, particularly when it’s their friends or family sharing them as opposed to a newspaper – people they actively trust. Moreover, the downside to personality politics is that it fails to take into account the whole picture, such as their party platform and their general aptitude as a politician, negotiator and leader. Social media is an innovative new outlet that exposes people to myriad of political news and opinions which they may not have noticed or spoken about before, which is good. However, just like with a newspaper, not everything you read on social media will be true nor impartial. While social media may be the future for politics and political campaigning, we should also be treating it with caution.

Close

Close