Posted by Dr. Laila Kadiwal, Research Associate at the Centre for Global Youth

Over the past few years, I have conducted a range of in-depth interviews with young people in Britain and Pakistan [1]. Youth attitudes towards politics was one of the key issues that these interviews touched upon, and over the summer, I have been reflecting upon the similarities and differences in their attitudes and experiences. This question is particularly interesting at this juncture as both countries are undergoing extraordinary political changes at the moment. In the UK, the youth vote has become significant in the context of older population predominantly choosing to leave the European Union. And in Pakistan, where nearly 64% of the population is below the age of 29, youth engagement is seen as significant to democracy in the country.

In this blog post, I will discuss two initial observations. These broad observations are likely to change as I explore the data in more depth to understand the nuances and variations in youth attitudes to politics. In Britain and Pakistan, the media have tended to depict Pakistani youth as apolitical and pessimistic. However, I will argue that young people in both countries are concerned citizens raising some of the key politically-critical issues.

Young people in both countries feel somewhat frustrated with politics

Across the spectrum of gender, ethnic and class affiliations, young people in my sample from both the countries see themselves as somewhat unrepresented and disheartened and frustrated with politics.

A majority of young British people in my sample preferred the Labour party over any other political party, but not without skepticism and issues with the broader nature of politics itself. For instance, a 19-year-old male Labour voter who identified himself as working class and from a mixed background studying at a university told me ‘I don’t think any party caters to my ideology and I think we need to have a radical overview of how the system works before they can actually represent us.’

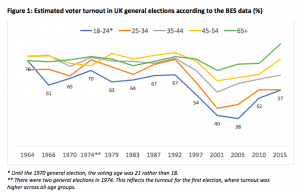

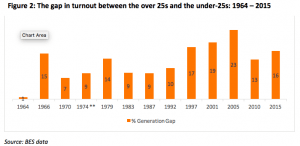

Some of these sentiments resonated with the ‘anti-politics’ discourse (Clarke et al. 2016) that seeks to bridge left and right and rejects current politics and parties. Many British youth in my sample felt less inclined to vote for varied reasons: they were not sure what politicians were promising them, they did not believe in politicians, or politics was not a significant aspect of their lives. This finds an echo in recent studies (e.g. Howker and Malik 2010; BSA, 2017; Pearce 2015) that suggest that young people believe that politicians do not address the issues which matter to them. The State of the Nation 2015 report highlights that young people care about different issues to those of the population as a whole. They ranked the NHS, unemployment, education, immigration and living standards as their top five key issues in the survey but did not feel that any political parties satisfactorily addressed these. Howker and Malik (2010) describe these young people as a ‘jilted generation’ that feels uncertain in terms of jobs security, affordable housing and stable future but does not believe that the political elites are listening to them.

Similar to the young people I spoke to in the UK, in Pakistan, youth found themselves disempowered in terms of representing themselves, holding the government accountable, and seeking justice. The participants raised issues around corruption, inequality and falling development indicators. They worried about inequality, inflation, inefficient public services and declining development indicators. They felt concerned about the law and order, road safety, corruption, nepotism, and crime, but the police and judiciary were perceived as serving politicians and bureaucrats. They felt aggrieved by inequitable access to resources and inequitable opportunities for development.

The key difference between the youth in the UK and those in Pakistan seemed to me the different degrees of hope and confidence about their future in their respective countries. Many young Pakistani felt hopeless and insecure and they feared about their and their families’ future due the falling development indicators, violence and the state of affairs in politics, whereas, most of the British young people in my sample group seemed to demonstrate a sense of optimism and hope that they lived in a developed country that stood among the top economies in the world and therefore, things will not be as ‘apocalyptic’ for them.

Young people are divided in their attitudes towards diversity

Another key political issue in both countries is the complexity of youth attitudes to the ‘other’. In Pakistan, politics is deeply intertwined with people’s ethnolinguistic identities. This is further exacerbated by the ideology of Pakistan as articulated in educational curricula that constructs an exclusivist and a narrow notion of who an ideal citizen is. Scholars and activists have argued that the national ideology of Pakistan underplays the religious and ethnic diversity of the nation; twists and omits important historical details (Aziz 2004); and glorifies militarisation and war (Hoodbhoy and Nayyar 1985). It presents India, Hindu, and British people as enemies of Islam (Nayyar and Salim 2002).

Historically, Britain has also faced difficulties in embracing diversity. In the past, the term ‘diversity’ carried a negative meaning in English from the late 15th century, as ‘being contrary to what is agreeable or right; perversity, evil’. In the 1650s, diversity also signified dissidence, derived from the Latin dissidentia. It is only in the late 20th century the term ‘diversity’ has acquired a positive connotation in policy discourse and the benefits have started to be embraced (Kadiwal, 2014). That said, values such as tolerance continue to be tested on issues involving gender and sexuality, multiculturalism and immigration in the UK. The ideology of the fundamental British values also continues to be controversial.

In my research, young people were not passive recipients of socially divisive political narratives; rather, they actively responded to diversity in light of their everyday life in Britain and Pakistan, and in reaction to the prevailing socio-political situations of their countries. Factors such as their socio-economic status, their education, and particularly the levels of issues affecting their local communities, in which they were located, influenced their perceptions of diversity.

Nearly all young Pakistani felt concerned about ethnolinguistic based politics and considered it as the cause of conflict. They felt aggrieved with the (mis)use of ethnic and religious differences to political ends and believed that the conflict among the political parties along ethnic and sectarian lines was one of the key barriers to their unity and development. Yet, young Pakistani appeared to relate to the questions of diversity differently in different contexts, and with different effects. Some of the most exclusivist tendencies in the sample group were demonstrated by male students in a conflict-affected and deprived area. Others, however, constructed non-Muslims as citizens with equal rights. Thus, young Pakistani constructed their relationship with the ‘other’ in multiple and contradictory ways.

Similarly, young British people were divided in their attitudes towards diversity and immigration in Britain. Some young British detested the political discourse of identity and immigration as being divisive. They argued in favour of a more open, mobile and outward looking society and appreciated diversity positively as an asset to the British economic and cultural life, whereas some young people said that their lives revolved around their home and their region and they did not wish to necessarily embrace the ‘other’.

Goodhart (2017) divides these opposite tendencies into ‘anywheres’ and ‘somewheres’. ‘Anywheres’ represent degree-educated and geographically mobile who embrace new people and experiences; in contrast, ‘somewheres’ are rooted in their home region and find the rapid change that mobility or migration overwhelming. It has been argued that this polarization is between those economically benefiting from globalisation and those marginalized from the benefits of globalization. Some have also argued that people embrace the ‘open’ versus the ‘closed’ outlooks in life; openness is about embracing an open economy and tolerant society, while closedness involved those wanting to keep competition and change at bay (Harding 2017). In my interviews, some young British people from a mixed background found themselves at the receiving end of what they perceived as racism, while, other young British believed that people from other cultures and countries were adversely affecting their chances for employment, housing, and education and jeopardising their safety, identity and their ways of life.

Conclusion

These discussions revealed young people in both countries as concerned citizens raising some of the key politically-critical issues. This contrasts with perceptions of politically apathetic youth in both countries and rather point to larger problems with political systems in both the countries. Across the spectrum of gender, ethnic, national and class affiliations, I saw young people asking vital questions that affected their lives directly but feeling to some extent unrepresented in politics. Young people actively engaged with political narratives in their micro-contexts of everyday lives and they actively responded to socio-cultural and economic diversity in light of their everyday life in Britain and Pakistan, but their reactions were not static, decontextualized or homogeneous. It was not always possible to neatly straightjacket young people in one position. Thus, I would recommend that as researchers we need a fluid, dynamic, and open theoretical framework to analyze young people’s attitudes towards politics.

Note

[1] My observations here are based on my research with young people in these two states. In 2017, I interviewed 13 young people (six females and seven males) between the ages of 15 to 24 on their responses to Brexit and the EU Referendum in a South-Eastern city of England. Eight participants identified themselves as the White British and five hailed from a range of mixed backgrounds. Prior to this, in 2015, I had interviewed 62 (32 females and 30 male) young people between 14 to 29 years in a Southern megacity of Pakistan on their perceptions of peace, education and conflict. In both the countries, youth participants hailed from a spectrum of socio-economic backgrounds (from marginalised to politically active; from out of school to elite and highly educated). A qualitative research approach was used, including semi-structured interviews and focus group discussion.

Additional References

Ali, Mubarak. 2002. “History, Ideology and Curriculum.” Economic and Political Weekly 37 (44/45). Economic and Political Weekly: 4530–31.

Aziz, K. K. 2004. The Murder of History: A Critique of History Textbooks Used in Pakistan. Lahore: Vanguard Books.

BC. 2013. “Next Generation Goes to Ballot.” Islamabad: British Council.

CCE. 2007. “Civic Health of Pakistani Youth: Study of Voice, Volunteering and Voting among Young People.” Islamabad: Centre for Civic Education Pakistan.

Hoodbhoy, P.A., and A.K. Nayyar. 1985. “Rewriting the History of Pakistan:” In Islam, Politics and the State: The Pakistan Experience, edited by A. Khan. London: Zed Books.

JI. 2013. Apolitical or Depoliticised? Pakistan’s Youth and Politics: A Historical Analysis of Youth Participation in Pakistan Politics. Jinnah Institute.

Nayyar, A. H., and Ahmad Salim, eds. 2002. The Subtle Subversion: The State of Curricula and Textbooks in Pakistan. Islamabad: Sustainable Development Policy Institute. http://unesco.org.pk/education/teachereducation/reports/rp22.pdf.

Filed under Uncategorized

Comments Off on Comparing youth attitudes towards politics in Britain and Pakistan: Some initial reflections

Close

Close

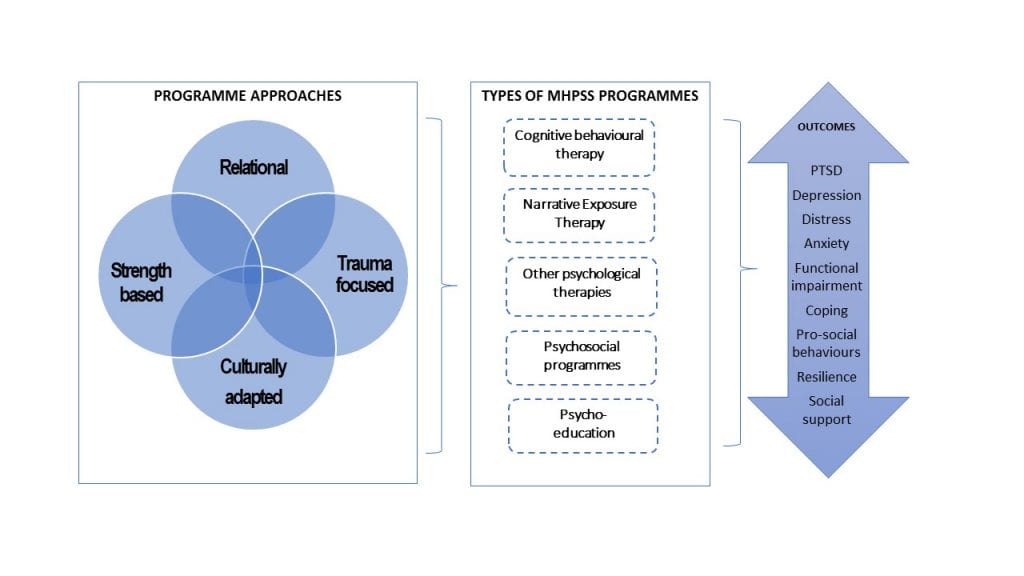

The United Nations Children’s Fund estimate that a quarter of the world’s children are living in countries affected by conflict or natural disasters. We know that these events can have a long-term impact on children’s and young people’s mental health and psychosocial wellbeing, and while many programmes have been designed to support children and young people dealing with the consequences, our knowledge of what works and why is still developing. To address this gap,

The United Nations Children’s Fund estimate that a quarter of the world’s children are living in countries affected by conflict or natural disasters. We know that these events can have a long-term impact on children’s and young people’s mental health and psychosocial wellbeing, and while many programmes have been designed to support children and young people dealing with the consequences, our knowledge of what works and why is still developing. To address this gap,

How did we get these findings?

How did we get these findings?