Piloting place-based and participatory youth research: lessons learned in Margate

By UCL Global Youth, on 16 July 2019

A guest post by Rachel Benchekroun, Research Assistant on the Youth attitudes towards mobility and migration project, and PhD student at UCL-IOE.

I am working on a small-scale project looking at mobility aspirations among young people in coastal towns (funded by UCL Grand Challenges, and co-led by Avril Keating, Claire Cameron, Abigail Knight and Jo Waters). As part of this project, we wanted to pilot a series of research instruments to explore questions such as (a) how can we incorporate arts- and place-based methods into our research practice? (b) how can we include more youth voice into our research process? and (c) what are the best ways to enable young people to become researchers in their own communities?

I am working on a small-scale project looking at mobility aspirations among young people in coastal towns (funded by UCL Grand Challenges, and co-led by Avril Keating, Claire Cameron, Abigail Knight and Jo Waters). As part of this project, we wanted to pilot a series of research instruments to explore questions such as (a) how can we incorporate arts- and place-based methods into our research practice? (b) how can we include more youth voice into our research process? and (c) what are the best ways to enable young people to become researchers in their own communities?

Fortunately, the Head of Citizenship at a secondary school in Margate was very keen for her students to get involved in the project, and in April and May of this year, I ran 3 workshops with a selection of Year 10 students. Here, I reflect on some of the practical things that I learned from these workshops.

The Pilot Project

When I first approached the school, I proposed working with a group of up to eight 16- to 18-year-old students for a couple of hours per week, over 3 consecutive weeks. In practice, it didn’t happen quite like this – the time of year, school timetable restrictions, and the teachers’ and students’ enthusiasm for the project meant that I instead found myself running the workshops with a lively group of twelve Year 10 students (aged 14 and 15) for just one hour per week. This created more pressure on time, and also limited the number of activities I could try out with the students.

For our first workshop, we decided to focus on introducing the students to the project and asking them for their views about the various arts-based research instruments we had developed. With this in mind (after I had outlined the aims of the project and obtained their informed consent) I asked the students to try out some of some of these tools, including

- A word association game (Describe Margate in 3 words!)

- Photo-response activity (using photos of Margate to gauge perceptions of places and feelings of belonging);

- Mapping exercise (drawing a map to show the journeys they make and feelings about places and spaces).

The students approached these tasks in a variety of ways – they were keen to share their views and debate meanings with each other.

Having consulted the students in Workshop 1, the aim of the second workshop was to encourage the students to become researchers in their own communities. We wanted students to try out our research tools with their friends, to give them an opportunity to become real world researchers, and to give us an opportunity to see how our tools would be used by Young Peer Researchers. With this in mind, much of Workshop 2 focused on explaining the ethical and practical considerations of doing research. And at the end of the workshop, I asked the students to try out our research tools with two peers at school by the following week. I provided them with two research packs each, which included a checklist, consent forms, and participant information sheets. They were asked to record their interviews if possible (using their mobile phones) and to bring all the data produced, as well as consent and information forms, to the final session.

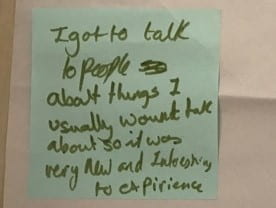

The primary purpose of Workshop 3, then, was to collect and analyse the data that our Young Researchers had collected, and to ask them to reflect on the experience of being a researcher. The students told us that they had really enjoyed the workshops, and in in Workshop 2, they had been enthusiastic about the idea of trying out the research tools with their friends at home.

The primary purpose of Workshop 3, then, was to collect and analyse the data that our Young Researchers had collected, and to ask them to reflect on the experience of being a researcher. The students told us that they had really enjoyed the workshops, and in in Workshop 2, they had been enthusiastic about the idea of trying out the research tools with their friends at home.

However, in the end only 5 of the 12 Young Researchers said they had undertaken some research, and of these, only one shared audio recordings and two shared transcripts of interviews. Two more said they would email notes of their interviews, but these have not been received. Two other patterns were striking: (a) The students only attempted to do the word association game with their friends, and ignored the other suggested activities (b) The peer interviews all appeared to be quite short in length (e.g. a couple of minutes in the audio recordings). While this was slightly disappointing, it has provided an opportunity for reflection, which can help us plan for the larger-scale research project.

Lessons Learned

Why did many of the students not carry out the peer research activities? This may be due to a lack of confidence, and/or difficulties organising themselves. At least one student had previously expressed reluctance about interviewing others. In the third session, another commented: ‘I tried to interview my friend, but he walked away!’ I feel that working with slightly older students, having more time to prepare the Young Researchers and providing opportunities for practice in pairs within the classroom (allowing them to take on the role of researcher) would have helped the students to undertake peer research.

Some students did not have a mobile phone or recording facilities, which may have deterred them from doing the research. Addressing this in advance with the help of the teacher might have overcome this.

Why did no-one try the mapping or photograph activities? The students may have found it difficult to plan ahead and to find the time and appropriate space within the school setting to do the interviews. It may be that including blank paper and felt tip pens in the Young Researchers’ packs would have made it easier for them to do the mapping activity with their peers. Whilst I had used printed photos for the photo activity, I had encouraged the Young Researchers to ask their friends to share photos of places from their phones – but expecting them to carry out the activity differently to how we did it in the classroom may have caused confusion. Making a list of who wanted to try out which tools and/or asking the teacher to provide time and appropriate space for the students to do their research as part of the next lesson might also have helped ensure all the tools were piloted.

Why were young researchers’ interviews so short (and data limited)? With only one hour per week, there was just enough time to try out the different research tools in session one, but with very little time left for discussion and analysis. Although I reiterated the importance of using the tools as a means of provoking discussion and reflection, and to a limited extent modeled this, the students themselves did not get the chance to practice the activities or the necessary skills in the classroom, which did not therefore facilitate in-depth learning for them to later put into practice independently.

Planning for the longer-term research project

We hope to build on the promising relationships with the school staff and students, and to work with key staff to embed the training and research process into the Citizenship curriculum. This will allow more time to explore and experiment with the research tools, to build up the students’ confidence and interviewing skills, and to provide more structured time and space for the young researchers to undertake research with their peers.

This project was funded by the UCL Grand Challenge small grant scheme in association with the UCL Grand Challenge of Cultural Understanding.

Close

Close