Reconstructing Broken Bodies: From Industrial Warfare to Industrial Engineered Tissues

By zclef78, on 5 July 2014

An illuminating and occasionally gruesome lecture for a non-medic unused to the visual realities of war, the third of the series UCL Lunch Hour Lectures on Tour marking the centenary of the First World War tackled a rarely discussed aspect of the aftermath of trench warfare.

The idea of the fabrication of living tissues to repair injuries is well publicised in the media today, from growing an ear on the back of a mouse, to full face transplants.

However, the development of reconstructive techniques was largely precipitated by the industrial scale of conflict in WW1.

Sadly, Professor Robert Brown (UCL Surgical Science) was unable to attend, so we were left in the capable hands of Colin Hopper (UCL Eastman Dental Institute) who delivered both the historical and medical sides of the lecture with distinctive candour.

Early medical advances

I was unconvinced that a GCSE in Biology would get me through the finer points of tissue fabrication, so it was a relief that we began with the historical context of medical advances during military conflicts since the early 1800s.

The fact that disease was responsible for a large number of deaths during the wars between 1804-15 was hardly a surprise, but the scale of the death–nearly 266,000 of the 311,806 deaths (85%) in the Army and Navy–showed just how much of an impact developments in medicine made to survival rates in future conflicts.

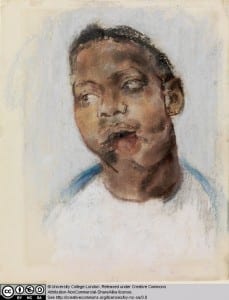

Changes in strategy and weaponry in WW1 caused a significant increase in the number of soldiers who sustained head and limb injuries, yet over 92% of wounded British soldiers evacuated to British medical camps survived. Some fairly horrific slides of facial injuries from more recent Iraqi and Libyan conflicts demonstrated the consequences of the types of weaponry used a hundred years earlier. Major General Henry Shrapnel has a lot to answer for.

As a head and neck surgeon, Colin was interested to know how much the audience thought a person needed of their face to survive. Drawing a line running from the top of the head and behind the ears with his hand, he revealed that anything below that line is an “optional extra”–who needs frontal lobes?

Close

Close