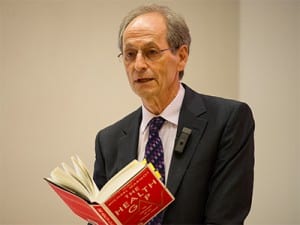

Sir Michael Marmot in conversation: “Social injustice is killing on a grand scale”

By ucyow3c, on 6 October 2015

![]() Written by Helen Stedeford (UCL Life & Medical Sciences)

Written by Helen Stedeford (UCL Life & Medical Sciences)

Public health expert Sir Michael Marmot introduced his book The Health Gap by sharing the story of Mary, a First Nations Canadian who hanged herself aged 14. Every case is tragically unique, however the suicide rate among young First Nations members is five times higher than for other young Canadians – why? The suicide rate for Indian cotton farmers is much higher than for Indians in other rural occupations – why? Poverty – at least that’s part of the answer.

Using case studies and population statistics, Marmot illustrated the social gradient in health, which is found in all societies; those at the top of the income ladder have low levels of disease and long lives, and with each step down the ladder the chance of physical and mental illness, and early death, increases. So began a fascinating evening of discussion between Marmot, The Lancet’s Tamara Lucas and audience members.

Exclusion

The distinction between absolute and relative poverty is important. At 54 years, the life expectancy of a man from the poorest area of Glasgow is lower than that of the average Indian man (62-3), although the income of the Glaswegian is higher. Marmot referenced economist Amartya Sen’s idea that relative financial disadvantage translates into absolute ‘capability’ disadvantage. You may have more money than someone elsewhere, but if you cannot afford to participate within your own society (e.g. pay your phone bill), you may be worse off.

Maximising freedom

So what are the costs of participation? Can/should we organise society differently to minimise them? UCL is associated with utilitarianism – the greatest good for the greatest number of people – however, Marmot prefers maximising “the freedom to live a life you have reason to value”. This entails creating the conditions that allow people to do this; for example, it is estimated that if the U.S. stopped subsidising its own farmers, the global price of cotton would rise by 6-14%: would this be enough to reduce the financial insecurity of Indian cotton farmers? Would this enable more of them to value life over death?

It is not only economic conditions that are relevant – the importance of early life circumstances is being found time and again to massively influence outcomes; how free are the choices of someone who has only ever known abuse?

Empowerment

Autonomy is one of the keys to improving health; educated women are much more likely to make their own fertility choices than uneducated women, and to have children who survive and thrive. Closer inspection of Mary’s story reveals that the many Canadian First Nations groups had similar levels of (terrible) poverty, but some groups had suicide rates twelve times higher than others. Those with lower rates all had some level of self-government and control over their own resources – social as well as economic capital affects health.

“Poverty is not destiny”

Fascinatingly, the social gradient is not confined to health. Socio-economic status (SES) massively impacts intelligence tests; a cohort study found that children who scored highest around age 2 also performed well at the age of 10 if they were from a high SES family, but if low SES their scores dropped. The effect was also found at the bottom; “if you’re thick and poor you stay thick, if you’re thick and rich you get a bit less thick”.

Educational level is a large determinant of future income so this seems to belie the subtitle above. However, Marmot reported it is the mantra of staff at a school in deprived Tower Hamlets; educational outcomes have historically been low there, but the head teacher was able to show that with deliberate shaping of the school’s culture, their performance had improved to equal the national average.

Change can happen

Marmot shared a number of examples of work that are having a major impact on communities, including a project run by the West Midlands Fire and Rescue Service with marginalised youth. As he described, it will take decades to know how this affects ‘hard’ health markers such as mortality. However, by monitoring intermediate outcomes such as education and employment, a map for the future can be constructed.

Marmot denies being political and suggests that binary political perspectives are a barrier to change, after all the health gradient affects those in the middle as well as those at the bottom. However, there is now a growing evidence-base for optimism against which policies can be usefully examined – the health gap can be closed.

As UCL President & Provost Professor Michael Arthur commented, academia would do well to remember that health is a much larger (and more interesting?!) field than medicine.

Close

Close