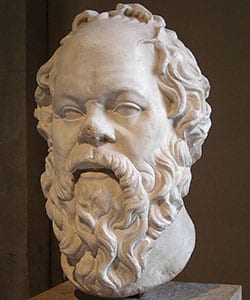

The gadfly of Athens

By Ben Stevens H P Stevens, on 20 February 2014

“You are the incarnation of the good life”. As opening gambits go, it’s a sure-fire way to win over an audience and a compelling way to begin a lecture about Socrates.

But then, through her extensive TV work, author and historian Bettany Hughes knows all about how to captivate modern audiences with tales from antiquity and her public talk, ‘Athens: the theatre for Socrates’ ideas’, on 13 February was no exception.

The lecture was part of Ancient Plays for Modern Mind – a public engagement programme organised by UCL Greek & Latin, which was certainly doing its job, judging by the large number of eager sixth-form students sat around me.

Hughes began the lecture proper by explaining the meaning behind her “incarnation” comment; that by attending her talk and engaging in face-to-face debate, we were participating in one of the joys of life – at least as far as Socrates was concerned.

Having recently been asked by a journalist why the philosopher is relevant today, she told us that, although she could have supplied them with a book-length answer, her eventual reply was much shorter.

Socrates asked fundamental questions about life – What is good? What is virtue? How do we live together – that still exercise us to this day. In particular, he argued that enquiry is essential to being human – hence his famous maxim, “The unexamined life is not worth living”.

A ‘doughnut subject’

Yet, one of the challenges that Socrates poses is that he didn’t write anything down. Everything we know about Socrates is hearsay, making him, in the words of novelist Mark Haddon, “a doughnut subject” – very rich, but with a big hole in the middle.

Even so, Hughes believes that writing a life of Socrates is still a worthwhile endeavour. When writing The Hemlock Cup: Socrates, Athens and the Search for the Good Life, her approach was akin to painting the space around an object rather than the object itself.

Plato, she explained, is our greatest source. He describes Socrates’ world in minute detail – demonstrating what we would now call episodic memory – and much of it is now matched by emerging archaeological evidence from Athens.

Moving on to the subject of that ancient city, she described it as Socrates’ “soul… his raison d’etre” and as a character in its own right in his story.

For Socrates, Athens’ ordinary citizens – such as the vintners and stonemasons – were the intended recipients of his ideas, while his relationship with those in power was much more problematic.

The rise of democracy

Democracy emerged during his life and, with its radical reordering of power, it spread like wildfire through the city-state. Many Athenians saw it as a panacea, but Socrates was not so convinced – he saw that it could soon be co-opted, especially as a means to levy taxes.

In this way, Athens soon became rich as it imposed democracy on neighbouring city-states. This gave rise to increasingly gaudy ostentation – a fact borne out by recent pioneering work carried out on Athenian statues at Copenhagen University.

Socrates placed himself in opposition to this materialism and, in later years, found himself increasingly at odds with his fellow citizens – becoming in Plato’s words a “gadfly’.

Boxing against shadows

Clouds by Aristophanes was this year’s UCL Classical Play and is, in large parts, a slander on Socrates by the then-22 year old dramatist, caricaturing the philosopher as little more than an atheistic charlatan. According to Hughes, Socrates felt the play left him “boxing against shadows” and that it was like a trial by media.

By the end of the 5th century, Athens, humbled by plague and Sparta, its confidence shaken, was no longer prepared to tolerate Socrates’ dissenting opinions. Thus, Athens, the bastion of freedom, tried and sentenced him to death for impiety and corrupting the youth.

However, in her conclusion, Bettany Hughes argued that Socrates loved life and would not have wanted us to dwell on his trial and death. Love was the one thing that he said he truly understood – it was what he drew from Athens, but also what he reflected back at the city.

Finally, she ended the lecture by exhorting us, just as Socrates would have done, to “live life better”.

Close

Close