Brain Anatomy and the Ancient Olympics

By news editor, on 4 July 2012

![]() Annette Mitchell, PhD student (UCL Greek & Latin)

Annette Mitchell, PhD student (UCL Greek & Latin)

Linking neuroscience and the ancient Olympics appears curious at first sight, but after hearing Professor Semir Zeki (UCL Neuroesthetics) express how neuroscience can illuminate ideological elements of the ancient Olympics these differing subjects proved to be a stimulating pairing.

Linking neuroscience and the ancient Olympics appears curious at first sight, but after hearing Professor Semir Zeki (UCL Neuroesthetics) express how neuroscience can illuminate ideological elements of the ancient Olympics these differing subjects proved to be a stimulating pairing.

The setting was a discussion on 28 June between Professor Zeki and Professor Chris Carey (UCL Greek and Latin) entitled The pursuit of Olympic ideals – physical, neural and aesthetic. Professor Zeki asked Professor Carey about aspects related to the ancient Olympics and concluded by providing neuro-anatomical explanations for them.

The Original Olympics

Professor Carey began by introducing the ancient Olympics, which is commonly believed to have first occurred in 776 BC. The Games were likely instituted so that the various ancient Greek city-states, which were often at war, could peacefully compete. The Olympic Games were, essentially, sublimated aggressive impulses.

Olympic competitors were, indeed, ruthless. In the pancrateon – a wrestling competition – any move, however harmful, was tolerated, provided it did not kill an opponent, which was “frowned upon”.

Athletics undergirded by aggression became part of the fabric of Greek culture. Indeed, everywhere the Greeks subsequently founded cites there were always wrestling arenas and gymnasiums (sporting grounds).

Conditions

Professor Carey then explained the insalubrious conditions at ancient Olympia. Located inland, crowds would have flocked there from across Greece and just two rivers, the Kladeos and the Alpheios, would have served as the main water supply, as well as the toilets. Due to the numerous sacrifices made to Zeus, flies would have been everywhere, alongside the numerous animals used for sacrifices.

However, despite this, the Olympics would have been entertaining, especially if you were lucky enough to be part of the elite. As well as the athletics, Greek elites could mingle and manage alliances. There would have been cultural events, political speeches and, even, temporary brothels.

Gymnasium culture

Professor Carey went on to describe the social aspect of athletics. Every city-state had a city Gymnasium, which was male-only and central to civic life. There, older men of high social status would watch attractive (young, nude and oiled) males practise sports. These high status males often took these young men as lovers, which, although occasionally disapproved of, was a generally accepted elite activity.

Physical beauty

These boys were desired because the male athlete’s body was regarded as an absolute ideal of beauty and health. Aristotle described the male athlete’s body as beautiful and capable of enduring much effort. (Female bodies were not idealised similarly and there was much less tolerance of female nudity).

Moral beauty

Ideology surrounding the beautiful male body was strongly linked to ideas about moral beauty. It seems that possessing a boy sexually allowed these men to possess a related moral beauty.

In Plato’s dialogue Charmides, Socrates is shown in a wrestling school discussing self-control. There he meets Charmides who, because of his beauty, is being pursued by many gentlemen. Socrates acknowledges that Charmides is beautiful but sees this as secondary to him having a good soul.

Reward

Lastly, reward was discussed. The ancient Greek ideology surrounding reward differs fundamentally from today. The Greeks would have seen silver and bronze placements as ridiculous. Greek athletes competed for glory, and humiliation followed any placing that was not first. Tangible rewards were symbolic; victors only received a vegetable crown, although occasionally athletes received a reward from their city-state. In Sparta, victors were honoured by being allowed to flank the king in war.

Brain Parallels

After discussing these aspects of the ancient Olympics, Professor Zeki explained that many of the features that surround the ancient Olympics share processing areas in the brain.

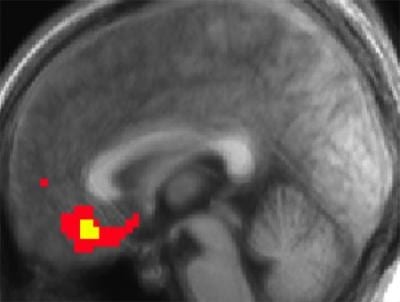

This implies that the related inclusion of these ideological aspects in the ancient Greek Olympics was not accidental but determined by the brain’s functional structure. The main example is the medial orbito-frontal cortex (pictured), which links moral and physical beauty with reward as it is activated when judgements are made concerning these three areas.

Another area mentioned was the parietal cortex, which explains concepts associated with the beautiful Greek male athlete’s body.

The parietal cortex is active in arithmetic, processes symmetry and integrates sensory bodily information. Symmetry and maths are central in a theory of beauty based on Fibonacci Numbers that uses a Golden Ratio to describe facial proportions deemed to be beautiful.

Interestingly in fifth century BC Greece, beauty in art and philosophy was linked to proportion, balance, order and symmetry. The parietal cortex’s processing of numbers, the body and symmetry, coupled with this mathematical theory of beauty, gives a cognitive explanation for aspects associated with ancient Greek ideals related to the male athlete’s beauty.

These illuminating explanations for ancient practices emerged from an unusual interdisciplinary collaboration. It shows that such collaborations can often be fruitful even if they do appear bizarre and should perhaps be encouraged to happen more frequently!

Image: The medial orbitofrontal cortex (Credit: O’Doherty et al/PLoS Biology)

Find out more about UCL’s programme of events and exhibitions to mark the Olympics and Paralympics

Watch the full lecture below:

Close

Close