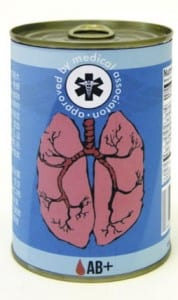

Organs for sale?

By Freya A Boardman-Pretty, on 15 June 2012

My friend was sceptical. “I don’t know, I think opt-out is too much. There’s enough information out there for people to make a decision.”

“But there clearly isn’t enough,” I said. “People are still dying!”

We were arguing about organ donation in the UK, and the hundreds of people a year that die waiting for a transplant. Should we introduce an opt-out system, so that those who do not elect to be removed from the register are considered donors?

I had been strongly in favour. The apathy of millions with no need for their organs after death, I thought, was leaving potential recipients to die.

But an event at the Cheltenham Science Festival challenged me to think again and consider new facets of organ donation. In Organs for Sale, Emily Thackray told her compelling story of the cystic fibrosis that devastated her lungs, and the transplant that eventually saved her life. Ethicist Bobbie Farsides and surgeon Keith Rigg joined in to discuss the wider issues.

The problem we face is effectively one of supply and demand. When organs deteriorate, medical technology may be able to step in – renal dialysis for kidney problems, for example – but in some cases only another human organ will suffice. And we don’t have enough: three people in the UK die waiting for an organ transplant every day. How do we reconcile the organs available with the numbers who need them?

In the UK, 80-90% of the public profess to support organ donation. Yet this doesn’t translate to a higher percentage on the register, with 29% signed up. Why? For many, I suspect it’s simply an issue of convenience and visibility.

I signed up to be an organ donor when applying for my drivers’ licence: it wasn’t something I’d thought much about before, and if I hadn’t had the question placed in front of me, it may have been a while before I gave it consideration.

Another audience member talked about being given the option to register when signing up for a Boots card. Is such increased visibility the right way to get people to sign up? Or will some, as Emily feared, resent having the question forced upon them when they’re not ready to make a decision?

So what of increasing incentives? The Nuffield Council on Bioethics has set out an ‘intervention ladder’ for promoting donation. The least drastic rung of the ladder is provision of information about the need for organs, while the top suggests financial incentives as a reward for the donor or their family.

How far up this ladder should we go? Where do you begin to feel uncomfortable? Personally, I was in favour of deceased donors having their funeral expenses paid, but Emily wasn’t sure. Families of recipients, she said, tend to use the ‘language of the gift’, to talk about the intense gratitude they have for the donor who made this altruistic move.

Would providing rewards somehow cheapen the whole process in the minds of potential donors?

And if we move to paying people or their surviving family for organs, does it change the nature of consent? One could imagine a potential living donor covering up a pre-existing health condition in order to receive much-needed money for a kidney.

As it stands, the World Health Organisation opposes any form of financial reward in exchange for organs, and Iran is the only country permitting payment to living organ donors. Direct sale of organs in the UK may not be a feasible option, but the idea makes us think about what tactics we can employ.

But as I began to consider – is the whole issue a red herring? How much do higher numbers on the register actually translate into more lives saved? The fact is that retrieving a functioning organ for successful transplant is not easy. Most potential donors die in the wrong place, and in the wrong way, for their organs to be usable: consent is only one of the barriers to successful transplant.

Take Spain, the country with the highest rate of organ donation in the world, and often considered a shining example of a system of presumed consent. This view, however, is missing the whole story. As Keith told us, Spain’s increase in transplants is largely due to improved infrastructure – to donor coordinators, to organ retrieval teams, to people dealing with the legal issues.

A lot of the barriers to transplantation lie in the hospital after a death. For example, what many don’t know is that the family of the deceased have the power to decide whether their loved one’s organs will be donated – regardless of their wishes. In a time of grief and stress, a family may not feel able to make such a decision.

This is why, stressed Emily, one of the most important things is to talk with your family now about your wishes. If they know what you want done after your death, they won’t be blindsided at a critical moment by a doctor telling them you were on the register. We need visibility, transparency, more talk about donation country-wide. Would public information campaigns combined with improvements in infrastructure bring the change we need?

An audience member said that if all non-donors could hear Emily’s story they would change their minds, and I had to agree. The talk gave us a lot to think about, including points I haven’t touched on – how to reduce the demand for organs in those with health problems, the needs and incentives for living donors – and it will be fascinating to see how the organ donation landscape evolves in future. What do you think: do we need to force people to face up to donation? And how should we do it?

Close

Close