Things seem brighter than they are

By Matteo Farinella, on 13 June 2012

I think my life is going to be better than yours. I will have more money, more success and live longer. This apparently doesn’t make me particularly arrogant, because when asked to rate themselves and their expectations, the majority of people place themselves in the top 25% of the population. Clearly some of us must be wrong, yet Tali Sharot argues that being wrong is not necessarily bad.

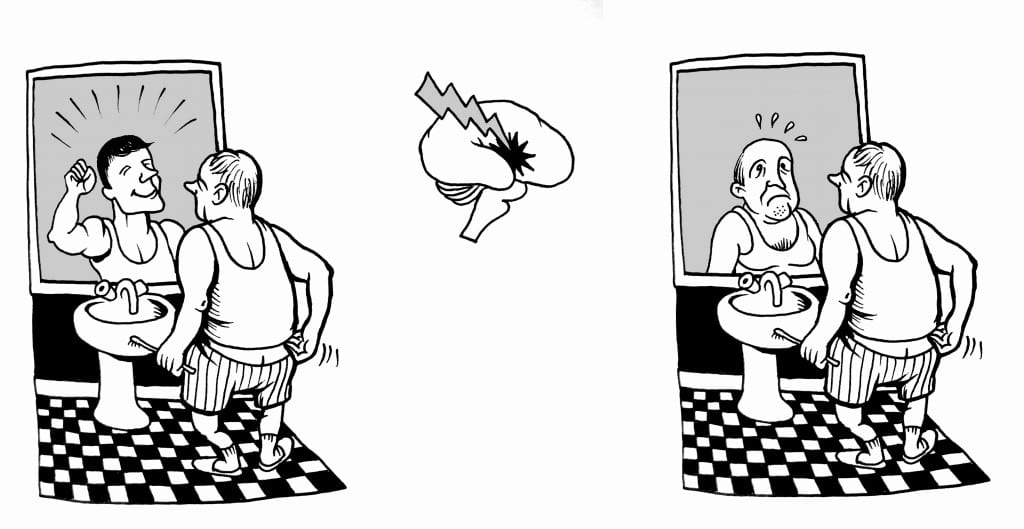

Optimism is defined as the tendency to overestimate positive outcomes and underestimate negative ones. As such, optimism is merely an illusion (just like the optical illusion above, where the balloon on the black background appears slightly brighter than the one on the white background, even if they are actually the same shade of grey). Then why do both human and non-human brains seem to be hard-wired for optimism? This is the question Dr Sharot tried to address in her talk, The optimism bias.

The most striking result from Sharot’s research is that not only are we initially biased in our expectations, but also in our ability to learn from experience. When confronted with real data, we are willing to change our beliefs in response to positive news, but not the other way around. This is reflected in brain activity, which strongly responds when results meet our optimistic beliefs, but tends to ignore negative results. Indeed, stimulating the unresponsive areas make us more realistic… the real question is: do we really want to burst the bubble?

Pessimism, or even a more realistic view of reality, seems to correlate with depression. Conversely, statistics suggest that optimists live longer and earn more money. Of course, there are also dangers. Any pessimist will warn you that great expectations can lead to great disappointments, but that does not seem to always be the case. Psychology experiments show that optimists tend to be less disappointed than others when their expectations are not satisfied.

For example, if they fail an exam, they will simply think that the questions were unfair and they will do better on the next one, while pessimists will blame themselves and lower their self-esteem.

The point that Sharot is trying to make is that optimism does not change objective reality but changes our perception of it, which in turn has great effects on our behaviour and mental health. If we expect positive outcomes, we will work harder to obtain them. If we expect nothing, that is most likely what we are going to get. The real challenge, then, is not to give up optimism but to minimise its risks and change our motivational strategies.

Here, in Cheltenham, is a good day, full of exciting science talks (or at least it seems). Come back soon for more news!

All images copyright Matteo Farinella – inspired by the talk and freshly drawn this morning. http://matteofarinella.wordpress.com/

Close

Close