The Body in Pieces

By David R Shanks, on 24 October 2011

‘The Body in Pieces’ selectively displays fragments from the UCL Great Ormond Street Hospital archive. Occupying a gatehouse building and part of the North Cloisters, this exhibition renders visible a curious collection of artefacts as they become objects of broad academic significance, after a former life at the Hospital’s research facilities, the UCL Institute of Child Health.

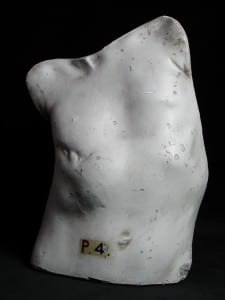

Most striking are the plaster casts that fill the windows of the ‘North Lodge’, visible to passers-by on Gower Street. This assortment of disembodied limbs and torsos document a variety of bone conditions found in young patients. Beautifully executed around 1870, all troubled from within and sparsely labelled, they leave huge scope for fresh interpretation.

After meeting Antony Hudek from the curatorial team and exploring the further displays within the North Cloisters, I was able better to understand the considerations behind the exhibition and the problematic nature of the UCL Great Ormond Street Hospital collection.

“I was initially assigned to the medical collections after joining the Mellon Program at UCL”, says Antony. “My colleague at the Royal Free Hospital was the conservator Paul Bates, who was on a mission to rescue several collections doomed to disposal, the Great Ormond Street collection being the star of these.”

Close to three thousand objects had been amassed since 1860 on the initiative of hospital founder Dr Charles West. The collection included around 80 plaster casts – often West’s specialty, limbs – but also many wet and dry specimens, wax models and ephemera. The utility of these teaching aids had declined as photography, despite its lack of tactility and three-dimensionality, became more popular, and in the mid-1980s when the collection was eventually retired to storage.

In 2007 the deprecated objects were under threat of being disposed of altogether, whereupon Paul Bates decided to covertly preserve them at the Royal Free Hospital. “When Paul saved the collection he hid specimens behind false walls in a seminar room because he was afraid that successive generations of doctors might not agree to house them. The seminar space was actually larger than people realised, but it was full of pots, thousands of them.”

Now at UCL the gatehouse display operates as an enigmatic provocation, a surrealist shop window of pale broken mannequins. To understand the full diversity of the collection it is necessary to move inside to the North Cloisters. “We had to produce this display to somehow contextualise [the plaster casts]. It turned out to be a good thing, because that’s when we got in touch with the archives of the Great Ormond Street Hospital, which opened up a new avenue of communication.”

Four wall-mounted vitrines are filled with record books, samples in jars, wax replicas of skin disorders, and mean little objects rescued from the digestive systems of young patients. These displays counterbalance the open ended visceral treats of the gatehouse with a more straightforward social history, and provide space to articulate difficulties with the collection. Pragmatically, its specimens depend upon a diminishing pool of craftspeople like Paul Bates, who possess a “rare combination of skills”.

“Many items are in need of restoration, and there’s a lack of the kind of experience gained over years and years of handling, day in, day out. They need to be treated with historical as well as technical care, and this is really difficult to learn except through practice.” Another shaping force of this ‘tip of the iceberg’ display relates to ethical considerations, namely the Human Tissue Act which severely limits the public display of human tissue.

Problematic in terms of both maintenance and display, the collection is nevertheless of great value. I could appreciate the craftsmanship in the fine plaster casts, executed by Louis Brogiotti (c.1818–1888), but to different eyes there are many other attributes worthy of analysis. Antony points out that “even the fluids in the sample jars have histories”, as their compositions have changed over time. “The skills to decipher and disseminate these histories are lacking.”

Problematic in terms of both maintenance and display, the collection is nevertheless of great value. I could appreciate the craftsmanship in the fine plaster casts, executed by Louis Brogiotti (c.1818–1888), but to different eyes there are many other attributes worthy of analysis. Antony points out that “even the fluids in the sample jars have histories”, as their compositions have changed over time. “The skills to decipher and disseminate these histories are lacking.”

In summary, the exhibition functions most successfully as a display of factors making the future of such a collection so uncertain, rather than being a static memorial to its past. Without meeting Antony I wouldn’t have spotted that the exhibition’s title, ‘The Body in Pieces’, referenced a lecture by art historian Linda Nochlin on the fragmentation of the body, nor appreciated how his arts background had so pervasively influenced its themes.

Did Antony believe that re-evaluating these objects from an artistic perspective could prolong and redefine their existence? “Absolutely, this is a second lease of life. Similarly to the ‘Culture of Preservation’ project here at UCL, we are interested in re-looking at these objects, deemed scientific, that have now attained the level of archival object with little remaining relationship to actual practice. Artistically they feel very peculiar, something quite disturbing that requires definition and yet resists it at the same time. Here the emerging idea of the artist as researcher becomes particularly relevant.”

The Body in Pieces runs until 14th December 2011.

The exhibition was curated by Paul Bates, Jayne Dunn and Antony Hudek, and Sussanah Chan built the displays in the North Cloisters.

At UCL, the exhibition relates to the Museums & Collections, The Culture of Preservation, and the Object Based Learning initiatives.

Further information about UCL’s links with The Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital is available on the GOSH website and the UCL Institute of Child Health website.

For more information on the Human Tissue Act 2004, see the Human Tissue Authority website.

One Response to “The Body in Pieces”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] specimens. Last year, one of the most fascinating collections was on display in the exhibition The Body in Pieces, late nineteenth century plaster casts depicting a variety of bone conditions from the young […]