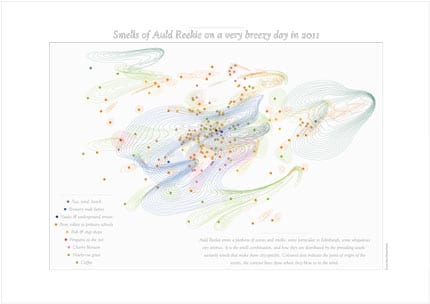

I’ve been thinking more about data visualisation and mapping, this time in terms of how to illustrate relationships between different medieval texts. In particular, I’ve been wondering how to show ways in which different medieval genres relate to each other.

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS nouv. acq. fr. 1104, fol. 79r.

This manuscript is filled entirely with lais, clearly labelled as such. The text at the bottom of the image reads ‘Explicit les lays de breteigne’ (The Breton lais end here).

As a genre, the lai is simultaneously strongly-defined and very ‘open’. On the one hand, lais have a strong sense of their own identity, usually expressed in their prologues and epilogues. Here they generally declare themselves to be lais, and contain several items from a fairly fixed list of lai characteristics (e.g. revealing the title of the lai, revealing that it is a tale of the ancient Bretons, declaring that the story is a true one). On the other hand, the types of texts calling themselves lais are so varied that it is difficult to come up with a satisfactory, stable definition; indeed, one of the best ways of deciding whether a text is a lai or not is if it declares itself to be one.

In the Middle Ages, short verse narratives such as the Breton lai were very flexible from a generic standpoint; shorter poems could be used as filler items in manuscript miscellanies, and could be adapted to suit a variety of different manuscript contexts. Within a manuscript culture, where texts had to be copied out each time rather than printed in bulk, there was no one set version of a text. Each copy had the potential to be slightly different, and lines of a poem – or entire sections – could be added or removed by the scribe of a new manuscript if the existing copy wasn’t to his taste (Paul Zumthor has called this phenomenon mouvance; the Wessex Parallel WebTexts project based at the University of Southampton has a very helpful discussion of this here). The way in which short verse narratives move between manuscripts has recently been the focus of a major cross-European research project, The Dynamics of the Medieval Manuscript, whose website also has a wonderful virtual exhibition about the manuscripts from the project.

In addition to their intrinsic flexibility, there is also a good deal of overlap between lais, fables, fabliaux and other short verse narrative genres, which often draw on a common pool of subject matter, style and imagery (for instance, both lais and fabliaux feature wandering knights who are granted wishes by fairies, although in the case of the fabliaux the wishes are somewhat more salacious). Even medieval texts themselves suggest that one type of story can develop from another. As the bawdy fabliau La Vielle Truande (The Old Woman) puts it in a semi-spurious etymology, ‘Fabliaux are made from fables, just as new music is made from notes […] and stockings and leggings from cloth.’ Occasionally, a text labelled as a lai in one manuscript will be called something else in another; for example, Oiselet (The Little Bird), describing a battle of wits between a bird and a peasant, is called a ‘lai’ in Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS nouv. acq. fr. 1104, and a ‘dit’ in Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS fr. 24432.

So, how to illustrate the relationships between different, but interrelated, genres of texts, where some of these could be classified as belonging to two, three or more genres? Well, one way in which several people have done this before is by creating new versions of the iconic London Underground map, created in 1931 by Harry Beck (click on the images to get larger versions):

The original 1931 design by Harry Beck

The 2013 Underground map

Adopted by subway systems all around the world from Lisbon to Shanghai, the abstract geography of Beck’s design is also a simple and elegant way of showing ways in which different categories of people, genres or ideas are interconnected. Since Simon Patterson’s The Great Bear, which replaced station names with those of actors, philosophers and other well-known figures, versions have been created exploring musical genres, Shakespearean characters, languages of the world, the human body, and even the structure of the Milky Way.

I’ve been playing around with the Tube map in relation to medieval texts, and have designed a test version showing the relationships between genres of Middle English texts. It follows roughly the same shape and colour scheme as the London Underground map (click on the image to get a larger version):

The yellow Circle Line has become the Canterbury Tales Line, with the various tales told by Chaucer’s pilgrims jostling promiscuously into almost every genre; the scarlet Central Line, which intersects with almost as many, has become the Romance Line (romance is even harder to define generically than the lai, and in Middle English the term can simply mean ‘a text translated from French’). The formica-pink Hammersmith and City Line, which runs alongside the Circle Line for several stops, translates nicely into the Fabliau Line, a well-represented genre in the Canterbury Tales. Breton lais follow the route of the green District Line; again, there is some overlap with the Canterbury Tales, with the linked stations of Wife of Bath’s Tale and Wife of Bath’s Prologue providing a speedy route from fabliau to lai.

The yellow Circle Line has become the Canterbury Tales Line, with the various tales told by Chaucer’s pilgrims jostling promiscuously into almost every genre; the scarlet Central Line, which intersects with almost as many, has become the Romance Line (romance is even harder to define generically than the lai, and in Middle English the term can simply mean ‘a text translated from French’). The formica-pink Hammersmith and City Line, which runs alongside the Circle Line for several stops, translates nicely into the Fabliau Line, a well-represented genre in the Canterbury Tales. Breton lais follow the route of the green District Line; again, there is some overlap with the Canterbury Tales, with the linked stations of Wife of Bath’s Tale and Wife of Bath’s Prologue providing a speedy route from fabliau to lai.

The black Northern Line has become the Dream-Vision Line, intersecting twice with the Canterbury Tales (the Nun’s Priest’s Tale and the Monk’s Tale, both of which contain dream episodes), once with the Romance Line (in the Romaunt of the Rose, a translation of the most influential of all medieval dream poems), and sharing several stops with the orange Debate Line and the dark blue Social Commentary Line. The light blue Fable Line also connects with two Canterbury Tales, and intersects with both the Canterbury Tales Line and the Dream-Vision Line at Nun’s Priest’s Tale interchange.

Three-way interchanges can also be found at Joeseph’s Trouble About Mary and the Wakefield Second Shepherd’s Pageant, two plays from the York and Wakefield mystery cycles which both retell episodes from Saints’ Lives and share elements of their comedy with the fabliau, with Joseph suspicious that ‘som man in aungellis liknesse/With somkyn gawde has hir begiled’ (some man disguised as an angel has deceived her with some trick) when confronted with Mary’s pregnancy. Indeed, the Miller’s Tale, twinned here with JTAM, knowingly burlesques the Annunciation in its tale of carpenter John, his enticing young wife Alison, and her romance with the student lodger Nicholas.

Finally, the silver-grey Jubilee Line has become the Saints’ Lives and Miracles Line, intersecting with Romance with the Arthurian Tale of the Sankgreal, Canterbury Tales with the Prioress’ Tale (a miracle of the Virgin) and Dream-Vision with the revelations of St Bridget of Sweden.

To be sure, Middle English genres don’t translate perfectly into tube map form; the Canterbury Tales isn’t really a genre (although story collections are), and it’s slightly cheating to count the Wife of Bath’s Prologue as a separate tale for the purposes of linking lai with fabliau. If you have any suggestions or additions, I’d be happy to hear them!

Nevertheless, this has been a really fun exercise, and has helped me to think about medieval genres from a very different perspective. The tube map form would also work well for looking at the ways in which short verse narratives interact; another version, containing only those short texts, may be on the cards. It might also be interesting to draw up tube maps for story elements and character types (along the lines of the Greater Shakespeare map), both for Breton lais and also for later fantastical stories such as fairy tales. Watch this space for possible further tube mappery…

Further reading:

Keith Busby, Codex and Context: Reading Old French Verse Narrative in Manuscript, 2 vols (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2002)

Paul Zumthor, Essai de poétique médiévale (Paris: Éditions de Seuil, 1972), trans. by Philip Bennett as Toward a Medieval Poetics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992)

(Click on the map for full-sized version)

(Click on the map for full-sized version) Close

Close