Lai in focus: Lanval

By uclfecd, on 22 October 2013

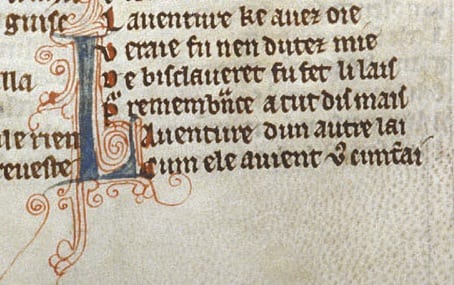

The final lines of Bisclavret and the beginning of Lanval, British Library MS Harley 978, fol. 133v. The last two lines read ‘Laventure dun autre lai/cum ele avient vus cunterai’ (Just as it happened, I will tell you the story of another lai’).

Lanval, a young knight far from home and overlooked by King Arthur, rides out alone from court. Reaching a meadow next to a stream, he dismounts to ponder his situation. Two beautiful girls dressed in purple approach and lead him to a sumptuously decorated tent, inside which lies la pucele/flur de lis e rose nuvele […] trespassot ele de beauté, ‘the maiden who surpassed in beauty the lily and the new rose’, wearing only her shift and a white ermine cloak. The maiden explains that she has travelled from her own country to find him, and that she will grant him her love, the ability to summon her whenever he chooses, and a magic purse which will never become empty, so long as he never reveals her existence. As Marie de France’s narrative dryly puts it, Ore est Lanval bien herbergez!, ‘Now Lanval was well-lodged!’

This happy state of affairs lasts until Lanval, angered by an insult from Queen Guinevere after he has turned down her advances, boasts that jo aim e si sui amis/Cele ki deit aver le pris/Sur tutes celes que jeo sai…Une de celes ki la sert/Tute la plus povre meschine/Vaut mieuz de vus, ‘I love and am loved by one who is more worthy than any other I know…Her lowest servant girl is better than you’. Not only does this break the spell, but the incensed queen demands that Lanval be killed unless he can provide proof of his boast. Arthur’s court now becomes a court of law, where Lanval is on trial for his life. Believing that he will never see his beloved again, Lanval is in despair. However, on the day of the trial, his lady rides into court on a white palfrey, le chef cresp e aukes blunt, ‘her hair curling and very blonde’, proving to all that Lanval was speaking the truth. Lanval then leaps onto the horse behind his beloved, and they both ride away to the enchanted Isle of Avalon, after which nul hum n’en oï plus parler, ‘no man has heard any more about them’.

Lanval is another lai first recorded by Marie de France. Her version appears in four manuscripts (MSS British Library, Harley 978; British Library, Cotton Vespasian B X IV; Bibliotheque Nationale de France nouv. acq. fr. 1104; Bibliotheque Nationale de France fr. 2168), the highest number of any of her lais other than Yonec, suggesting the popularity of this Arthurian tale. It was also translated into Old Norse as Janual, and twice into Middle English; firstly as the fourteenth-century Sir Landevale, which appears both in manuscripts and early printed editions as late as the seventeenth century, and secondly as the late fourteenth-century Sir Launfal, a jaunty tail-rhyme adaptation of the earlier Middle English translation. This second translation, which brings a more popular, mercantile tone to the aristocratic French original, also appears to provide us with the name of its creator, declaring in its closing lines that ‘Thomas Chestre made thys tale/Of the noble knyght Syr Lanvale’.

Much more recently, the story of Lanval has been adapted twice in the early twentieth century: as part of stage show Kissing the Wind by storyteller Cat Wetherill, which reworks three of Marie’s lais, and as a full-length film, Sir Lanval (2010), produced with the Brittany-based Centre de l’imaginaire Arthurien by the Chagford Filmmaking Group, who have made some beautiful films of a number of British fairytales.

With its outsider hero and fairy-mistress heroine, suspense-filled trial, and last-minute escape, it is easy to see why Lanval has appealed to so many adapters, translators and audiences over the centuries. You can read the entire French tale online in Judith Shoaf’s excellent English verse translation, and the Middle English version is available here.

Close

Close