Film review: Sir Lanval

By uclfecd, on 31 January 2014

Some time ago now, I wrote about Lanval, a knight-meets-fairy-mistress lai first recorded by Marie de France that has survived in Old French, Middle English and Old Norse versions. Somewhat more recently, it was made into a rather charming film by the Chagford Filmmaking Group, a Devon-based organisation specialising in films of British fairy tales. Made in 2010 in collaboration with the Centre de l’Imaginaire Arthurien, and directed by Elizabeth-Jane Baldry (who also composed the film’s score), Sir Lanval is the group’s first full-length film, and a delightful, whimsical retelling of the medieval lai.

Based on Marie de France’s twelfth-century version of the tale, Sir Lanval follows the same essential plot: Lanval, a young knight of King Arthur’s court, meets a fairy (named here as Tryamour) who grants him her love and unlimited wealth, on condition that he keep their relationship secret. However, goaded by Queen Guinevere, who attempts to seduce him and then sneers that he evidently prefers vallez…bien afeitiez, ‘well-trained young men’, when he refuses her advances, Lanval rashly declares that he already has a lover far more beautiful than the queen. At this, the spell is broken and Tryamour disappears, leaving Lanval to be put on trial for his life after Guinevere successfully convinces her husband that the knight had first propositioned and then insulted her. On the day of the trial, Tryamour rides into Camelot and vindicates Lanval, before the lovers leave the court forever en Avalun,/Ceo nus recuntent li Bretun, ‘to Avalon, or so the Bretons tell us’.

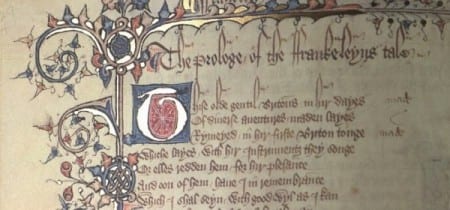

In adapting Lanval for the screen, Baldry and her team have created a gorgeous-looking film, shot in idyllic, bluebell-suffused woodlands in Dartmoor and Brittany, with the Château de Comper in Paimpont Forest (thought to be the legendary Brocéliande, in which many Arthurian legends are set) used for Arthur’s castle. The vivid, saturated greens and blues of the early summer landscape, along with the brightly-coloured costumes (the purple gowns of Tryamour’s handmaidens, pictured above, work particularly well), give the whole film the hectic, bejewelled palette of an illuminated manuscript. There are some lovely pieces of set design, too – the gaudy fantasy of Tryamour’s fairy banquet, where roast dragon is served alongside Eden-red apples and flying fish skewers, is a particular highlight.

Ian Hensher’s Lanval is a coltish, gawkily uncertain youth, civilised and ennobled by the love of the beautiful, accomplished Tryamour (played with sultry grace by Lori Macfadyen), but unable to control his temper when rebuffing the queen. Guinevere herself (played teetering on the edge of pantomime villainess by Maxine Fone) is expanded as a character, becoming more morally complex; though she is shown to be vain and vindictive, imperiously banishing any woman she suspects of winning Lanval’s favour, she is also given an additional motivation for seducing Lanval when it is revealed that Arthur (a bluff Mark Freestone) is more interested in meeting with his counsellors than producing an heir.

Another effective expansion is the emphasis placed on the role of gossip and rumour. The losangers – flatters, tattle-tales and liars – are shown to be the enemies of true lovers in many Old French romances, bringing covert trysts to the ears of wrathful husbands and unsympathetic outsiders, and Baldry’s Sir Lanval presents loose talk as a catalyst for the story’s events from the very beginning, with Tryamour’s maidens lamenting Lanval’s inability to keep a secret in the opening scene. After Lanval is accused by the queen, Arthur is initially shown attempting to keep the scandal contained, until the rising volume of whispers in Camelot means that he has no choice but to put him on public trial.

Overall, Sir Lanval is a spirited interpretation of Marie de France’s lai, capturing the playful – and sometimes menacing – atmosphere of the medieval poem. Whether you’re familiar with the original texts or new to the Lanval story, this version of the tale is well-worth watching.

Close

Close