New map: Breton lai motifs

By uclfecd, on 30 October 2013

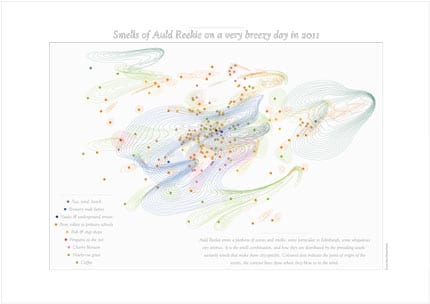

(Click on the map for full-sized version)

(Click on the map for full-sized version)

I’ve been continuing to experiment with ways of visualising the Breton lai metadata I’ve been collecting, and the latest visualisation I’ve created is a map of Breton lai motifs.

One of the types of metadata I’ve been adding to my database of lais and lai manuscripts (which will eventually become an online catalogue) is the themes and motifs included in the stories. The prologue shared by the Middle English lais Sir Orfeo and Lay le Freine (both c. 1330) provides a lengthy catalogue of the sorts of things one might expect to find in lais:

Layes that ben in harping

Ben y-founde of ferli thing:

Sum bethe of wer and sum of wo,

And sum of joie and mirthe also,

And sum of trecherie and of gile,

Of old aventours that fel while;

And sum of bourdes and ribaudy,

And mani ther beth of fairy.

Of al thinges that men seth,

Mest o love, forsothe, they beth.[Lays performed on the harp are about composed about marvellous things: some are about war and sadness, and some about joy and happiness; and some are about treachery and deceit, about old adventures from the past; and some contain jokes and bawdiness, and many are about the Otherworld. However, most of all they’re about love.]

I wanted a way of showing all these topics – as well as more specific motifs – which would allow the viewer to see which lais they appear in, and also to highlight instances where a motif or theme appears in more than one lai. Essentially, I’ve gone back to the Tube map idea of lines and stations, where each lai is a line, each motif is a station, and motifs shared by more than one lai are interchange stations. However, this is a much freer version of the design than my Middle English genres map, with curved lines, a different colour scheme, and ‘interchange stations’ made of increasing numbers of concentric circles according to the number of lais containing the motif. For this map I’ve just included the twelve lais by Marie de France; anything more would have made the page far too busy.

The map certainly bears out the observations made in the Orfeo/Freine prologue – ‘Mest o love, forsothe, they beth’ – with ‘love’ featuring as a major theme in all but one lai (only Bisclavret, with its focus on lycanthropy and human nature, doesn’t really spend much time on love). ‘Fairy’ is also shown to feature in two of Marie’s lais, Lanval and Yonec (where a woman falls in love with a fairy knight who can turn into a hawk), as does ‘trecherie and…gile’ in the shape of the faithless wives in Equitan and Bisclavret.

Some more specific motifs also appear in several lais. ‘Birds’ feature in three tales: Yonec, Laüstic (where a nightingale’s song provides cover for a lovers’ meeting) and Milun (where lovers communicate by letters tied to a swan). ‘Cloth and clothing’ also form key parts of the plot in three lais: Fresne (where recognising a piece of brocade leads to a reunion between mother and daughter), Bisclavret (in which the hero is unable to turn back into a human without his clothes) and Guigemar (where Guigemar and his lady exchange a shirt and belt just before they are separated). ‘Trees’, meanwhile, appear both in Frene (where the infant heroine is discovered in an ash tree) and Chevrefoil (in which Tristram places a signal for Iseult on a hazel branch).

To an extent, of course, this map is subjective in what it includes, and is by no means an exhaustive summary of lai contents. The shape of the curves also meant that it was difficult to zig-zag back and forth with individual lais to create all the possible connections. For instance, both Guigemar, Chevrefoil and Yonec also contain unfaithful wives, although in this case the wives are the heroines (only the ‘bad unfaithful’ are included on my map). However, hopefully it provides a helpful and accessible overview of the ‘ferli thing’ found in Marie’s lais!

Close

Close