Lai in focus: Bisclavret

By uclfecd, on 16 August 2013

Bisclavret is one of the twelve lais in Marie de France’s collection, and there are also two closely-related versions amongst the other Breton lais which have survived: Biclarel and Melion (it was also translated into Old Norse as Bisclaretz lioð). Clearly, this was a popular narrative, and it’s easy to see why; telling the tale of the shapeshifting werewolf Bisclavret, who is forced to remain in wolf form after his unfaithful wife hides the clothes which allow him to turn back into a man, this lai contains love, betrayal, dark tangled forests, and a gruesomely specific revenge in which wolf-Bisclavret bites off his former wife’s nose (incidentally cursing her female descendants with noselessness). It’s also a thought-provoking exploration of what it means to be human; do outward accoutrements of civilisation, such as clothing, make the difference between humanity and beastliness? Or should inner virtues, such as good manners, self-control and clear-headed thinking, be seen as more significant?

A Beauty-and-the-Beast tale with a difference, the characters in Bisclavret keep switching roles; the wife’s fear of her husband’s wolfish nature leads her to become monstrous in her turn, tricking him into permanent wolfhood whilst she marries a new lover. After a year in the woods, Bisclavret escapes death at the jaws of the royal hunting dogs by licking the king’s foot and begging for mercy, which allows his inner intelligence to be seen. Becoming a lupine royal lapdog, sleeping by the king’s side and loved by all his companions, Bisclavret remains at court until chance brings his wife and her new husband into the king’s orbit. Bisclavret attacks them ferociously, saving the most savage punishment for his wife:

Oiez cum il est bien vengiez:

Le neis li esracha del vis.(Just hear how successfully he took his revenge. He tore the nose right off her face.)

Subjected to torture by the king – suggesting that even the most courtly of monarchs has a bestial side – his wife confesses, and produces Bisclavret’s clothes. These, it is explained by the king’s wise counsellor, must be donned observing the rules of human propriety in order for the transformation to be successful:

‘Cist nel fereit pur nule rien,

Que devant vus ses dras reveste

Ne mut la semblance de beste […]

Mut durement en ad grant hunte!(Nothing would induce him to put on his clothing in front of you or change his animal form […] it is most humiliating for him!)

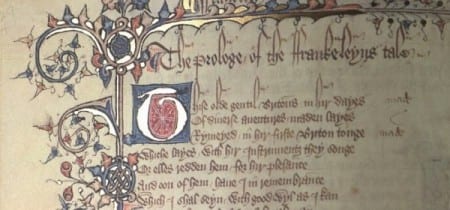

Bisclaret and its analogues is one of several werewolf tales circulating in the Middle Ages – others include the French romance Guillaume de Palerne (c. 1200) and the Latin Arthur and Gorlagon (13th/14th century) – and the notion of shapeshifting wolf-men clearly resonated with medieval audiences. Many encounters with werewolves are presented as historical fact, such as that of the historian Gerald of Wales, whose treatise on the geography and folklore of Ireland, Topographica Hibernica (c. 1188) includes an account of a young boy and a priest who meet an elderly couple turned into wolves by a curse. Meanwhile, bestiaries of the period credited wolves with various unsettling qualities, including the ability to rob a man of his voice by looking at him (should this happen, the only way for him to save himself is to remove his clothes and bang two rocks together, according to authorities such as the Aberdeen Bestiary – the image above, from a British Library manuscript, illustrates this situation).

In the twenty-first century, the story of Bisclavret, with its moral as well as physical shapeshifting, has been explored in a lovely short animated film by Emilie Mercier (France, 2011), which offers a more sympathetic portrait of Bisclavret’s wife. Some clips of this are available on YouTube:

Bisclavret, dir. Emilie Mercier (France, 2011)

Washington-based group Grendel Babies also have a song called ‘Wife of Bisclavret’, which retells the story from the wife’s perspective to a smokily jangling accompaniment of piano and screeching rock violin, adding a honky-tonk yowl to the multiplicity of voices which have retold the story from the twelfth century onwards.

Meanwhile, the figure of the sympathetic werewolf continues to prowl through popular culture, appearing in Charlaine Harris’ Sookie Stackhouse novels and the hit HBO series True Blood they inspired, and – in perhaps the most pervasive sympathetic werewolf image of the past few years – Twilight, in which the relationship between a werewolf and his clothes is also given attention (happily, werewolves are revealed to have higher-than-average body temperatures when in human form, meaning that fewer clothes can be worn for convenient removal when shape-shifting; this also allows werewolves to carry their clothing with them, an innovation which would have saved Bisclavret a lot of trouble).

What other latter-day Bisclavret figures are there?

Further reading:

Marie de France, Bisclavret, in The Lais of Marie de France, 2nd edn, trans. by Glyn S. Burgess and Keith Busby (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1996)

Leslie A. Sconduto, Metamorphoses of the Werewolf: A Literary Study from Antiquity through the Renaissance (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008)

Close

Close