States of Nature: Environmental Policymaking: Sustainable Development through formal state-based regulation in the urban Global South

By ucfuwu2, on 10 June 2014

Mallika Kosolsak and Jiayi Wang

Key Words: sustainable development, hazard, eviction, housing upgrade, community participation, bottom-up approaches

Introduction

This essay examines the national slum and squatter upgrading programme (Baan Mankong) launched by the government in Thailand in 2003 and implemented through the Community Organizations Development Institute (CODI). We will evaluate whether this case met the criteria of sustainable development.

Background

The programme aims at providing housing loans and infrastructure subsidies to poor communities to help upgrading and improve new houses. This support is given to community organizations, which are formed by the poor people who take part in the projects as well as those who work with them, such as city authorities, other local participants, academies and national agencies. It attempts to “go to scale” by aiding thousands of community-driven initiatives on city-wide plan. Urban poor networks can design and manage plans themselves towards developing long-term, comprehensive solutions to land and housing issues in cities in Thailand (Boonyabancha, 2005).

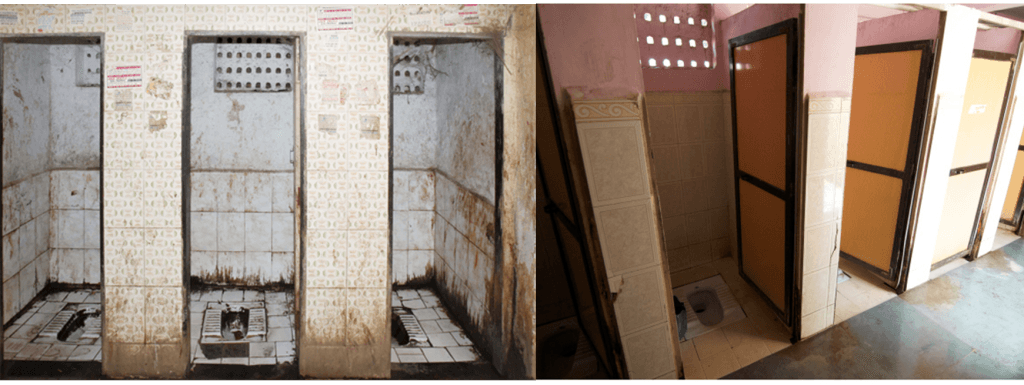

Case Study: “Bang Bua community”

“Bang Bua community” was the first canal-wide community upgrading project in Bangkok. There are 3,400 families living in twelve informal communities along Bang Bua Canal. They joined this programme in 2004 after living in with the risk of fire hazards and eviction for a long time. The project involved building same size houses, which enhanced a more egalitarian neighborhood and encouraged connectedness between social groups. Furthermore, a public access pathway along the canal was built for walking, biking, vending, playing, and emergency vehicles (Smithsonian, 2011).

The result of upgrading does not only improve the built environment, but it has many social benefits within the community. For example, a baan klang (“welfare house”) was built for elderly and disabled people who need care and this has become a model for other communities. The community also set up a welfare fund to subsidize school fees for the poorest children, for libraries, and play groups for all children and so on (Smithsonian, 2011).

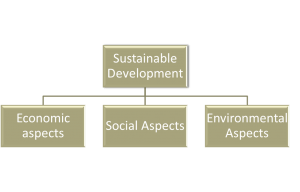

The Political Ecology Framework and Sustainable Development

The Brundtland Report (1987) defines sustainable development as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (The Bruntland Report, 1987) Social, environmental and economic sustainability are the three main aspects of sustainable development. Sustainable development is the core principle of the “Baan Mankong” programme. It shows how sustainable actions can be undertaken in with a bottom-up approach and adapts sustainability to different scales (from local to national and from national to international).

Policy Implementation

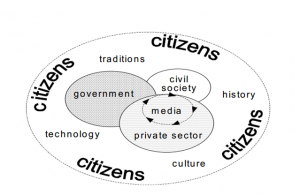

The policy of upgrading and developing community housing at a national scale was “people-driven”, and consisted in a new form of governance that shifted away from top-down methods. Fig. 1 presents the administrative structure which divides the upper level, where most decision-making occurred, from the community level, where operations were implemented (Posriprasert and Usavagovitwong, 2006).

At the institutional level, the Thai government launched the project in 2003 (Archer, 2010), regarded as one of its major policies. The Community Organization Development Institute (CODI), as the main actor and facilitator of program, was in charge of the overall process of the project, which involved guidance, supervising and funding processes and outcomes. CODI established a collaboration with other institutions including NGOs, banks, local universities, planners and architects for long-term investments (Archer, 2010). These organizations had the capacity to help communities use local resources sustainably and to control and manage pollution in the long run. Local government authorities were in turn responsible for financial support. This included housing and land loans, infrastructure subsidies and administrative subsidies.

On the “operations” level, the working group for housing development (WGHD) was set up to collect data, survey, to plan and manage the project. The community groups and organizations that fall in this bracket were key actors and stakeholders of the project.

The administrative structure therefore satisfied social justice, as the people’s voice was heard and put at the center of the city’s long-term development. It provided opportunities and created a space for interaction between poor communities, government authorities, professionals and NGOs to establish cooperative work on the housing problems and long-term development in cities.

Fig. 1: The main administrative structure

The implementation of policy requires several steps that involve the programme’s key actors and stakeholders. Because each community had different degrees of willingness to participate, the first step was to explain its aim and identify stakeholders. The second was to organize meetings within communities to name a joint committee and continue to upgrade plans (Community Program and Lanka, 2008). The final stage was to integrate pilot projects in the city-wide development. In this process, every stakeholder had equal rights to participate and share his or her ideas.

Reasons for success

The main reasons why the implementation of the policies was successful fall under social, ecological and economic considerations. On the social level, people-driven policy was the key to effectiveness. A bottom-up policy implementation approach allows urban low-income community organizations to control their own funding. In terms of housing strategies, all stakeholders had equal rights to participate and design their own settlements. In this way, a strong sense of participation and inclusion came to flourish. Although the poor were perhaps “weak” in financial terms, they are particularly strong in terms of working collectively. Restoring balanced ecological conditions was a result of people demanding clean and secure shelter, safe water and infrastructure for long-term sustainable development. On the economic level, government agencies provide funding directly in the form of housing and land loans, infrastructure subsidies and administrative subsidies, allowing residents to invest their savings elsewhere. Each community has a savings group to manage budgets efficiently. “People-driven” policy was the inspiration behind the project that enabled stakeholders to control the overall process and ensured it was a success.

Conclusion

There are many lessons to be learnt from the programme. In order to acheive sustainable development we must be simultaneously concerned with the environmental, the social and the economic. The aim is to further a sustainable present and future. Sustainable development also aims to enhance a strong, healthy and socially just society, meeting the basic needs of all people within the communities, improving their wellbeing and building a strong society with equal rights. There are notable benefits that emerge from social groups, specialists, local authorities, local institutions and universities working together with local communities. Finally, bottom up approaches may be a sustainable way of implementing large-scale management. Local people should play an important role in driving change in their localities. This would help to create the sense of community, the sense of belonging and the sense of place. Local people should participate in every process, including in decision-making and in the management of budgets. Finally, investment should focus not only on community development but also on social growth, harnessing the potential of the people to build sustainable communities themselves.

CITE THIS ARTICLE

Kosolsak, M. and Wang, J. (2014). Bangkok – Slum Upgrading | UCL Encyclopaedia of Political Ecology. [online] Available at: https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/esd/category/bangkok-slum-upgrading-project/

Bibliography

Archer, D., (2010), Empowering the urban poor through community – based slum upgrading : the case of Bangkok , Thailand. Empowering the urban poor, 46, pp. 1–11.

Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR), (2008), ‘A conversation about upgrading at Bang Bua’, International Institute for Environment and Development, pp. 1–10.

Baan Mankong Collective Housing Website. [Online]. Available at: http://www.codi.or.th/housing/aboutBaanmankong.html. [Accessed 11th March 2014].

Boonyabancha, S. (2005), ‘Baan Mankong: going to scale with ”slum” and squatter upgrading in Thailand’, Environment and Urbanisation, 17, pp. 21-46.

Design Other 90 Website, (2011), ‘Bang Bua Canal Community Upgrading’. [Online]. Available at: http://www.designother90.org/solution/bang-bua-canal-community-upgrading. [Accessed 3rd April 2014].

Posriprasert, P., and Usavagovitwong, N., (2006), ‘Communities’ Environment Improvement Network : Strategy and Process toward Sustainable Urban Poor Housing Development’, Journal of Architectural/ Planning Research and Studies, 4, pp. 53–70.

United Nations, (1987), ‘Brundtland Report, Our Common Future’, Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development.

Close

Close