Good Governance in the Niger Delta

By ucfuwu2, on 10 June 2014

Julia Mauer and Evelyne Saelens

.

Key Words: sustainable development, good governance, stakeholder negotiation.

.

Introduction

There have been many attempts at achieving sustainable development in the Global South. Good governance techniques that recognise the interconnection between nature and society have more of a potential to achieve sustainable development than those that do not. This report will assess the success and/or failure of such techniques in the case of the Niger Delta.

Background

The Niger Delta is an oil-rich region in the South of Nigeria that makes up about 7.5% of the country’s landmass. Nine of Nigeria’s 36 states are typically considered part of the Niger Delta regions – Abia, AkwaIborn, Bayelsa, Cross River, Delta, Edo, Imo, Ondo and their rivers.

There has been an on-going conflict in the Niger Delta since the 1990s over tensions between foreign oil corporations, who have a very strong presence in the area and the citizens of the Delta region, particularly minority ethnic groups, who feel they are being exploited and who are not receiving any socioeconomic benefits from the oil industry’s activity. Zalik describes the region as one ‘marked by a history of state and petroleum industry collusion both in social repression and environmental destruction’ (Zalik, 2004: 401). Social control of the Delta has largely relied on ‘petro-violence’, a term coined by Michael Watts (2001) to describe the joint security imposed by the Nigerian military and oil companies to police their installations and the environment of social unrest that surrounds petroleum extraction.

The rights of the inhabitants of the Niger Delta region have been undermined or ignored altogether both by the government and foreign oil corporations. Petroleum extraction is an environmentally destructive process, but one that has high economic returns. The inhabitants of the Delta are not being compensated for the destruction of their lands, and continue to lack basic needs. Shell is the most prominent corporation in the Delta and is a source of much controversy. As Zalik notes, ‘Shell remains the most visible manifestation of social control and regulation in a region that is otherwise bereft of basic services, including transportation and infrastructure’ Zalik (2004: 411). Resident of the Niger Delta reportedly complained that ‘in the Niger Delta Shell is the state’ (Zalik, 2004), indicating inadequate governance from the central government.

Applying the political ecology framework.

1. Political Ecology

Michael Watts is a prominent scholar in the field of good governance and he defines Political Ecology as follows: ‘Political Ecology is the study of the relationships between political, economic and social factors with environmental issues and changes’ (Peet and Watts, 1996: 6). Political ecology understands the relationship between society and nature in the context of growing capitalism. Political ecology is, then, an appropriate lens through which to examine the Niger Delta because of the presence of foreign oil corporations fulfilling their capitalist imperative of profit accumulation through exploitative activity.

2. Sustainable Development

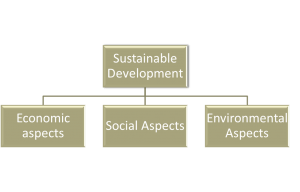

For this case study we must consider the goals of sustainable development, which incorporate economic, social and environmental aspects. Achieving sustainable development should cover these 3 aspects:

Figure 1. Sustainable Development Framework

Defining social injustice rather than social justice is more fitting here, given that social justice is achieved through the eradication of social injustices. We use Barry Levi’s definition of social injustice as the unequal distribution of benefits and burdens; or as he puts it, as the ‘denial or violation of economic, sociocultural, political, civil, or human rights of specific populations or groups in the society based on the perception of their inferiority by those with more power or influence’ (Levi, 2005). Environmental injustice relates to the following: unequal access to environmental resources, unequal distribution of hazards, and the interdependence of all species, and right to be free from ecological destruction (Principles of Environmental Justice, 1991)

An important notion within the framework is the distinction between processes and outcomes. In the context of the case study of the Niger Delta, we argue that both processes and outcomes are equally important. A just process does not guarantee a just outcome and vice versa. Good governance is the attempt to align just outcomes with just decision-making processes, in order to achieve socio-environmental justice.

3. Good Governance

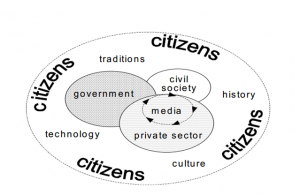

Swyngedouw defends that beyond-the-state-government (institutional arrangements of “governing”) is one of the new governance techniques. Graham (2003) argues that good governance should involve different actor groups.

Figure 2.

Source: Graham, J., Amos, B., Plumptre, T., (2003), ‘Principles for Good Governance in the 21st Century’ Policy Brief no.15, Institute on Governance, p.1

A dark shadow on the Niger Delta

The current problems in the Delta can be placed within the framework as follows:

- Social Injustice

- Nigerian population stays poor despite abundant oil resource extraction

- Local government fails to deliver basic services to the population

- Oil revenues go to federal government

2. Environmental Injustice

- Oil spills are environmentally and thus socially destructive (political ecology position of link between environment and society)

- Shell’s extractive practices cause the oil spills (through poor maintenance of pipes, etc.) but the inhabitants of the Delta are those that are burdened with the consequences

- Petroleum extraction is a highly polluting activity

Shell’s Initiative

Over the past two decades, Shell has intervened in attempts of good governance initiatives in the Delta region. Initially, they had been working on a community assistance program but ‘in response to considerable social unrest and bad press in the mid-1990s, Shell adopted a new approach in dealing with the Niger Delta in 1998, known as partnership development’ (Lapin, 2000, cited in Zalik, 2004: 402). They aimed to achieve a ‘social licence to operate’ – something many foreign oil companies sought at the time. They described the approach as being based on the 4 P’s: ‘peace, partnership, progress and prosperity’ (Zalik 2004: 408). The initiative arose because of a lack of state involvement and thus a need for a different form of governance.

Unfortunately, there were many problems with this initiative. The initiative was inherently contradictory ‘due to the financial incentive that is the industry’s bottom line […] the oil industry’s practices contribute to shaping the political economy of conflict in the Delta’ (Zalik, 2004: 407). Furthermore, the initiative was not sustainable because it was owned and therefore directed by Shell, as opposed to the local community. Lastly, Zalik noted that despite the improved image, violence has increased even further and states that ‘the partnership approach has not resolved the socio-environmental context of violence surrounding operations’ (Zalik, 2004: 410).

Developing Good Governance in the Niger Delta

More recently, there have been further efforts towards good governance in the Delta to improve social, economic and environmental justice and ultimately move towards sustainable development. The Department for International Development (DFID) funded a five year collaborative programme with Living Earth Foundation (a British NGO) and the Academic Associates Peace Works (A Nigerian NGO) ‘to encourage collaboration between government and civil society in the Niger Delta in order to improve governance and transparency in the region and by so doing, improve the delivery of basic services critical to the reduction of poverty’ (DFID website). The programme draws on the commitment and expertise of five Nigerian NGOs with ample experience of working with all stakeholders in the region. Working collaboratively, they offer a unique opportunity to engage government, civil society and the oil industry in engendering significant changes in behaviour and practice, which are pre-requisite to sustainable development (Living Earth website).

The project aims are the following:

- Better provision of basic services in Niger Delta

- Reducing poverty

- Enhanced effectiveness of civil society in the Niger Delta

The project activities are the following:

- Developing partnerships between local government, NGOs, communities and oil companies working in the Niger Delta

- Supporting the Nigerian government’s current SEEDS and LEEDS (State/Local Economic Empowerment Development Strategies) reforms through a participatory process involving a broad based stakeholder group

- Facilitating the implementation of pilot projects in order to demonstrate best practice approaches

- Building the capacity of Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) to question malpractice and demand better governance

- Engaging the wider public in the Niger Delta to identify the principles of governance and to promote transparency with their own traditional core values

The project activities make clear that beyond-the-state-governance and the involvement of many different actor groups are extremely important aspects of this project.

Conclusion

The Living Earth Project was still in the process of being assessed at the time of writing. We therefore cannot comment on its success in achieving good governance in the Niger Delta. It is important to note that engaging civil society does not automatically lead to good governance and we must question who is “responsible” for governing space. However, to achieve a certain level of sustainable development, it seems more effective to look at a greater scope that includes many stakeholders despite Graham’s (2003) argument that including more stakeholders makes ‘governing’ more difficult. Hence there is an on-going tension between the outcome and the process of good governance that is difficult to resolve given the importance of both. Nevertheless, adopting a political ecology framework enables us to navigate between the two.

CITE THIS ARTICLE

Saelens, E. and Mauer, J. (2014). Good Governance in the Niger Delta | UCL Encyclopaedia of Political Ecology. [online] Available at: https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/esd/good-governance-in-the-niger-delta/

.

Bibliography

Barry S., L., Victor W., S., (eds.) (2003), Social injustice and public health, (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Delegates to the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, (1991), Principles of Environmental Justice, Washington DC, [Online]. Available at: http://www.ejnet.org/ej/principles.html. [Accessed 12th April 2014].

Graham, J., Amos, B., Plumptre, T., (2003), ‘Principles for Good Governance in the 21st Century’ Policy Brief nNo.15, Institute on Governance.

Living Earth Website, [Online]. Available at: http://livingearth.org.uk/projects/developing-good-governance-in-the-niger-delta/. [Accessed 10th April 2014].

Peet, R. and Watts, M. J., (eds.), (1996), Liberation Ecologies: environment, development, social movements, (London: Routledge).

Swyngedouw, E., (2003), ‘Urban Political Ecology, Justice and the Politics of Scale’, Antipode35(5), pp. 898- 918.

The Department for International Development (DFID) Website, [Online]. Available at: http://goodgovernancenigerdelta.ning.com. [Accessed 10th April 2014].

Watts, M. (2001), ‘Petro-Violence: Community, Extraction, and Political Ecology of a Mythic Commodity’, in Watts, M. and Peluso, N., (eds)., Violent Environments, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press).

Zalik, A. (2004), ’The Niger Delta: ‘Petro Violence’ and ‘Partnership Development’, Review of African Political Economy, 31(101), pp.401-424.

Close

Close