Communities, Locality, Resilience and Sustainability : Achieving Resilience in the Urban Global South.

By ucfuwu2, on 10 June 2014

Katherine Ma and Martina Heuser

Key words: sustainable development, resilience, locality, scale, urban development, community participation.

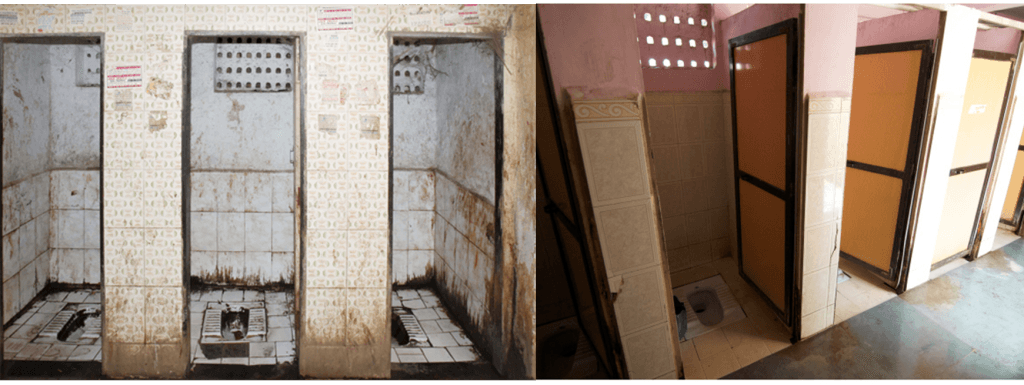

Toilets in the slums in Mumbai before (left) and after (right) the implementation of the programme. Image 1: Mammoth Website (2011) Image 2: MHS Blog (2010)

.

Introduction

This essay examines the framework of sustainable development, with special attention to resilience, locality, scale and community. These terms will be analysed through the case study of the Mumbai Slum Sanitation Programme by Shack/ Slum Dwellers International (SDI). The case will be evaluated by illustrating its achievements and possible drawbacks.

Background of SDI

SDI is a transnational Federation, founded in 1996 that operates as a network of national federations of local slum dwellers at different scales in 33 countries worldwide. It links urban poor communities from cities across the Global South in order to transfer and adapt problem-solving strategies (Tandon, 2010). Their main aim is to develop inclusive, « pro-poor » cities, which can be achieved only when ‘the urban poor [are] at the centre of strategies for urban development’ (SDI Website).

Case Study Mumbai: Slum Sanitation Programme

The sanitation situation in Mumbai is an example where pro-poor provision is lacking, as half of the city’s population lack adequate toilets. Whereas the city provides public toilets in poor living areas, they are maintained by the Conservancy Department of the government. This leads to no real local « ownership » and the toilets quickly become defunct. Furthermore, communities typically cannot decide on the location of the toilet, which means that they are built where it is not necessarily convenient for the local population.

In 1994, the municipal authorities decided to start a new programme to provide toilets to one million people living in Mumbai’s slums. In order to improve the implementation of the programme, a new mechanism was put in place to involve communities in the process of design, construction, management and maintenance of the toilets. The SDI Federation was one of three contractors selected to construct these community toilets. By 2005 more than 328 toilet blocks and 5,100 seats were built (World Bank, 2007).

The positive outcomes are visible on multiple levels. First, the toilets were located so that all members of the population were able to access them. Moreover, the toilets have improved lighting and ventilation systems, so that it was safe to go to the toilets, an important consideration for women and children at night, who benefit from improved privacy. In some blocks, small seats were built especially for children, as well as toilets suitable for the elderly and disabled. Finally, there was sufficient water for cleaning and the community-based maintenance means that the toilets are still functional years later.

The involvement of the community in the planning and implementation process of new toilet blocks meant that a less expensive and more efficient way of meeting the sanitation needs of slum residents was achieved.

Applying the Political Ecology Framework

a. Sustainable Development

In the Brundtland Report (1987), sustainable development is defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (Bruntland Report, 1987). Social, environmental and economic sustainability are the three main pillars of sustainable development.

Sustainable development is the core value of SDI. SDI aims to build sustainable communities and to show how sustainable actions can be undertaken with a bottom-up approach, especially in social and environmental aspects. It also adapts sustainability to different scales, from local to national and from national to international.

b. Resilience

Resilience is a measure of persistence of systems and of their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationships between populations or state variables (Holling, 1973). SDI introduced this system of adaptation and change to slums in Mumbai and other places by involving local people’s capacities. The process of planning and construction empowered people, and the new toilets improved people’s living standards.

SDI also acts as a bridge between communities and government to resolve local problems. This relationship can be straightened when the two parties work hand in hand to tackle the problem; or it can be weakened, if communities develop an ability to manage issues themselves, without any help from the government.

c. Community

Community resilience refers to people working together and helping themselves in times of adversity. It is often understood as a form of empowerment, with people attempting to manage their own problems. In this sense, SDI can be said to have empowered communities, which were place-based – shack or slum. The process of empowerment was positive for a redistributive sense of justice within classes or social strata, as people are involved in the process of planning and construction. This engenders an improved condition in what Fraser (2003) calls ‘politics of recognition’.

d. Scale

As mentioned, sustainable development discourses are bound by scale. However, scales are always produced, rather than priori or neutral. They are the product of political decisions. When decisions are rescaled, different actors acquire influence and different values get promoted or relegated (Griffin 2013). In the SDI context, this could happen when empowerment takes place in the community and the roles of different actors changed.

e. Locality

Local can be a site of agency in favour of changes. SDI has therefore adopted a bottom-up approach, implementing strategies at local levels. Where these have been successful, they have been applied to other regions. Hence, the local can be an effective scale at which to implement change.

.Conclusion

Is SDI moving in the right direction towards resilience in the Global South? In assessing the organization, we can find some weaknesses and some notable achievements. SDI uses a global network to reach governments, international organisations and donors. Moreover, their positive results from various cases around the world convince authorities of the effectiveness of the community-led approach. Furthermore, there is evident success of capacity-building processes at different scales –individual, organizational and systemic. Finally, SDI creates a space for local action and mobilisation, brings communities together and enables them to work on finding solutions to multiple issues including education, health and domestic violence.

However, we can also critique SDI’s scheme for resilience from different angles. While resilience can be used as a governance tool, we must pay attention to ‘who has the power to determine what is acceptable, to whom, via what political process’ (Hudson, 2009: 13). Moreover, as localism is not inherently sustainable or democratic (Brown and Purcell, 2005), it is worth examining power dynamics in the communities. For example, who speaks for the slum dwellers and what happens if there is disagreement? It is possible that the state displaces previous governmental responsibilities onto communities as a way of reducing its own responsibilities (Norris et al., 2007). These are the questions that require further investigation in order to unravel whether the implementation of resilience is truly successful.

.

CITE THIS ARTICLE

Ma, K. and Heuser, M. (2014). Communities, Locality, Resilience and Sustainability : Achieving Resilience in the Urban Global South. | UCL Encyclopaedia of Political Ecology. [online] Available at: https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/esd/communities-locality-resilience-and-sustainability-achieving-resilience-in-the-urban-global-south-a-case-study-of-shack-slum-dwellers-international-sdi/

.

Bibliography

Brown, C. and Purcell, M. (2005) ‘There’s nothing inherent about scale: political ecology, the local trap, and the politics of development in the Brazilian Amazon’, Geoforum, 36 (5), pp.607-624.

Derissen, S., Martin F. Quaas, and Stefan Baumgärtner, (2011), ‘The relationship between resilience and sustainability of ecological-economic systems’, Ecological Economics, 70 (6), pp. 1121-1128.

Fraser, N., and Honneth, A., (2003), Redistribution or recognition?: a political-philosophical exchange, (London : Verso).

Gibbs, D., and Krueger R., (2007), ‘Containing the Contradictions of Rapid Development?’, in Krueger, R and Gibbs, D (eds.) The Sustainable Development Paradox: Urban Political Economy in the United States and Europe. (New York : Guilford Press), pp. 95-122.

Holling, Crawford S., (1973), ‘Resilience and stability of ecological systems’, Annual review of ecology and systematics, 4, pp. 1-23.

Hudson, R., (2009), ‘Resilient Regions in an uncertain world: wishful thinking or practical reality ?’, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society,3 (1),pp.11-25.

Mammoth (2011), Website. [Online]. Available at: http://m.ammoth.us/blog/2011/09/fecal-politics/.

MHS Blog. (2010), [Online]. Available at: http://microhomesolutions.wordpress.com/2010/05/18/european-style-shared-bathrooms-in-indian-slums-it’s-acceptable-workable/.

Patel, S., Burra, S., and D’Cruz, C., (2001),’Slum/Shack Dwellers International (SDI) – foundations to treetops’, Environment and Urbanisation 13 (2), pp. 45-60.

Satterthwaite, D., (2001), ‘From professionally driven to people-driven poverty reduction: reflections on the role of Shack/Slum Dwellers International’, Environment and Urbanisation 13 (2), pp. 45-60.

Shack/Slum Dwellers International (SDI) Website. [Online]. Available at: http://www.sdinet.org. [Accessed: 1st December 2013]

Tandon, S., (2010) ‘The South-South Opportunity Case Stories: Slum Dwellers International – Mutual learning for human development’, [Online]. Available at: http://www.impactalliance.org/ev_en.php?ID=49485_201&ID2=DO_TOPIC. [Accessed: 1st December 2013]

Watts, M. (2004), ‘The sinister political life of community: Economies of violence and governable spaces in the Niger Delta, Nigeria’, Berkeley, California: University of California, Institute of International Studies, Niger Delta Economies of Violence [Working Papers 3].

United Nations, (1987), ‘Brundtland Report, Our Common Future’, Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development.

Close

Close