Jin Gao, Yangming Zhang, Linminqing Wang, Yawen Li, Feichi Li, Shirley Chang, Jiawei Liu

Figure 1: the V&A’s Chinese Export Watercolours image collection, and the whole list can be found on V&A Explore the Collections.

Chinese export watercolours are a type of objects produced in China for export to Europe and the North America during the 18th and 19th Centuries. They were made by Chinese artists catering to the taste of their customers, and these works typically depict Chinese traditional customs, occupations, manufacture and trades, boats, plants and animals, and they blend Chinese and European painting techniques, resulting in a unique mix of artistic styles. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) holds a significant collection of the Chinese export watercolours (Clunas, 1984), and despite its importance in global art history, this collection remains relatively understudied.

This blog, co-authored by students and staff, introduces the phase one of the Chinese Export Watercolours (CEW) project, which is a collaboration between the Chinese Iconography Thesaurus (CIT) project team at the V&A’s Asia Department (V&A, 2016) and the UCL Department of Information Studies, and it is funded by the UCL Fellowship Incubator Awards. The project is led by Dr Hongxing Zhang and Dr Jin Gao, and it has involved Molly Fort, a UCL PhD student, nine UCL students from the MA/MSc in Digital Humanities programme (Yangming Zhang, Linminqing Wang, Yawen Li, Feichi Li, Shirley Chang, Jiawei Liu, Xiaohan Jiang, Liyuan Liu, José Pedro Sousa), as well as Yi-Hsin Lin and Bingjun Liu, the CIT data standard editors at the V&A. With the kind support from UCL Digitisation Suite and UCL Centre for Digital Humanities, the project started in May 2023. It has involved cataloguing, auditing, photography, and digital asset management works of over 2,300 Chinese export watercolours acquired by the V&A in the 1870s to 1930s.

Figure 2: The project team photo. From left: Linminqing Wang (MSc student in Digital Humanities, UCL), Xiaohan Jiang (MSc student in Digital Humanities, UCL), Yangming Zhang (MSc student in Digital Humanities, UCL), Yawen Li (MSc student in Digital Humanities, UCL), Molly Fort (PhD Researcher, Institute for Sustainable Heritage, UCL), Jin Gao (Lecturer in Digital Archives, UCL), Liyuan Liu (MSc student in Digital Humanities, UCL), Feichi Li (MA student in Digital Humanities, UCL), Hongxing Zhang (Senior Curator of the Chinese Collections, V&A)

Thanks to the help and guidance by the V&A’s Asia department, the V&A Research Institute (VARI), the Photography and Digitisation, the Collections Care and Access, the Digital Media and Publishing departments at the V&A, phase one of the CEW project has resulted in an updated collection catalogue and digitised images on the V&A Explore the Collections website accessible as teaching and research materials for all, and for phase two, it is carrying out image analysis and archive-based provenance research to trace its history of collecting and investigate the formation of the collection.

Cataloguing and pre-photography

Benefitting from the training offered by the V&A’s curatorial staff in object handling, the initial phase involved basic cataloguing and pre-photography tasks, typically requiring a collaborative effort between two individuals. One person was responsible for measuring the dimensions of albums and paintings using plastic rulers, while another recorded these measurements in a spreadsheet along with additional details such as box notes, inscriptions, and the condition of the paintings. Additionally, prior to photography, the pre-photography staff attached object numbers to small white papers and placed them on each painting to aid colleagues in later stages.

The experience of pre-photography tasks could be described as a mix of enjoyment and precision. The enjoyment stemmed from the chance to closely examine the paintings as they were laid out on the table. This hands-on interaction felt almost like a journey back in time, allowing us to connect with historical figures and get glimpses into their lives. Some paintings evoked laughter, while others challenged our assumptions about what Qing China looked like. However, the process demanded careful attention to detail. For the person measuring, seemingly identical paintings might actually have slight differences in their dimensions. For the cataloguing task, encountering unfamiliar and complex characters in traditional Chinese text was common. Despite these challenges, facing them head-on was essential for improving our digital skills and achieving the precision necessary for museum work.

Figure 3: three students working on the cataloguing and pre-photography tasks of albums containing the Chinese Export Watercolours.

Photography

The photography of these watercolours played an important role in the overall digitisation process, and we would like to express our gratitude to the UCL Digitisation Suite for letting us use their digitisation equipment. We, as students, had received basic digitisation training through the Introduction to Digitisation module as part of the UCL Master programme in Digital Humanities. Benefitting from the further training provided by the V&A Photography and Digitisation department, we learned many practical aspects such as camera setup, lighting adjustments, colour management, and post-processing techniques, which greatly facilitated the project’s initiation. For the specific process, capturing the needed photograph demanded the close coordination of two to three members of our team. One or two of us took charge of positioning the object, adjusting its angle and location on the copy stand, and fine-tuning the camera’s height. Meanwhile, another team member operated a laptop, utilising Capture One — a photography software suite — to remotely manage the camera’s focus and capture settings.

Figure 4: The Kaiser copy stand in the project photography lab

During the initial stages of our project’s pilot test, arriving at consistent camera settings necessitated multiple trials and discussions. While time-intensive, this phase laid a sturdy groundwork. Subsequent shots only required us to adjust the camera height and focus based on the batch’s object sizes. Our primary objective was to capture each artwork with highest resolution, ensuring legibility of labels at the frame edges. Typically, the initial photo in each batch featured a colour checker — a critical tool for colour calibration during post-processing. Following these preliminary steps, we moved on to photograph each artwork individually.

Figure 5: The colour checker put alongside the target object

Occasionally, we encountered objects that posed challenges in terms of capture. While most artworks have flat surfaces, some exhibited signs of aging, leading to wrinkles in their mounts. Thick albums, when opened to certain pages, would bulge at the centre. To minimise this, we employed a large transparent glass panel, an action that often resembled weightlifting due to its heft. Careful handling was essential to prevent damage to the delicate pith paper. In such instances, an extra pair of hands often came in handy for observing, page-turning, and manual straightening. Reflective materials — like gold pigments or protective plastic films — presented a unique hurdle. We would reposition the artwork to eliminate glare and capture these paintings in segments, later stitching them together during post-production. Likewise, for larger paintings, we applied a similar approach, capturing sections and subsequently merging them.

Figure 6: The interface of auto-stitching function in Capture One

In essence, the photography phase was one of the essential stages of our digitisation endeavour. Through careful handling and innovative techniques, we aimed to capture each artwork with the highest fidelity, ensuring their lasting preservation in the digital realm.

Colour management

The raw images underwent post-photography processing utilising Capture One. This phase encompassed the addition tasks of metadata, including creator details, CIS (Common Information Subsystem), copyright information, and related information. Additionally, image rotation and cropping were applied on a case-by-case basis, ensuring the focus remained on the primary subject of the painting and enhancing its aesthetic appeal.

An important juncture in our process was colour calibration, a step that presented numerous challenges. Variations in lighting conditions during photography and variations in camera height could lead to deviations from the original colours. Thus, colour calibration based on the previously captured colour checker was imperative. However, we encountered disparities when using different colour calibration software. Although the same colour checker produced dissimilar ICC files across different software, our extensive comparisons led us to favour the ColourChecker Camera Calibration method. This approach yielded results closest to the original paintings and became our best solution.

Given the variations in Capture One across different computer systems, careful attention was required to standardise subtle options and settings during the collaborative colour calibration process. Any deviation in these settings could lead to significant discrepancies in colour calibration effects. An illustrative example is the Export option ICC Profile, which ideally should be configured to Embed Camera Profile. Selecting Adobe RGB, on the other hand, resulted in heightened vividness and a reddish tint post colour correction.

Figure 7: The screenshot of post-production task on Capture One

The post-production stage proved to be a time-intensive endeavour, with an approximate output of around 100 images per day. Upon completion of the initial tasks, the photography team actively participated in the post-photography phase, further streamlining our efforts.

The image quality check

Ensuring access to top-quality images from the CEW project’s painting collection is crucial for visitors. Our process started with checking each object on the V&A website using its system ID and object number. We began by downloading the first JPG image of the object and evaluating its quality following the V&A websites terms and conditions. If it met the quality standards, we noted the review date in the ‘V&A website check’ column in our tracking spreadsheet to make sure all paintings were covered.

Specifically, we encountered a few issues that need addressing. One common problem was inconsistent cropping, where paintings were not adjusted properly, displaying the object number unnecessarily. Another issue was image quality problems like dots or unclear images. We reported these issues to the V&A Collection Management team and Digital Media team for fixing. After that, we double-checked to ensure the corrections were made properly.

Figure 8: The ‘technical glitch of dots’ during image quality check

Our responsibility for delivering high-quality images and easy access on the V&A website was crucial. It ensures visitors have a smooth experience without any problems while browsing the webpage and viewing images.

The digitisation of the Chinese Export Watercolours collection marks a significant milestone, and it opens up more opportunities to further explore this collection. As we move forward, more project updates will be anticipated.

The annotation via Zooniverse

The digitisation of the Chinese Export Watercolours collection marks a significant milestone, and it opens up more opportunities to further explore this collection.

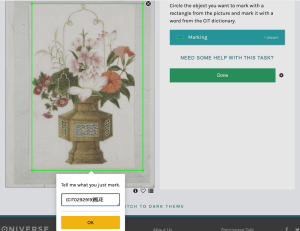

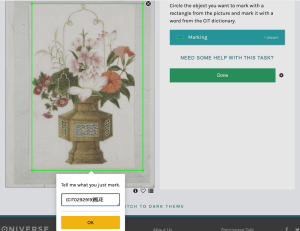

For example, to facilitate the annotation process, we have used the Zooniverse platform, a citizen science portal managed by the Citizen Science Alliance (Simpson et al., 2014). Zooniverse hosts some of the internet’s largest, most successful crowdsourcing projects, enabling volunteers worldwide to engage in scientific research. The platform provides user-friendly annotation tools that allow participants to mark content and subject matter in drawings, and the CEW project will leverage Zooniverse’s technical support, and project team members will embark on thematic and content labelling for the initial pilot collections.

Figure 9: the Chinese Export Watercolours project homepage on Zooniverse

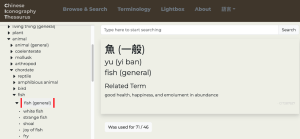

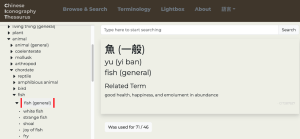

We will, firstly, employ Zooniverse to thematically annotate the collection, utilising vocabulary derived from the Chinese Iconography Thesaurus (CIT). Given the CIT’s robust descriptive system for Chinese collections, we will be adopting this vocabulary for CEW collection labelling. This approach establishes continuity between our research project and the CIT.

Figure 10: the Chinese Iconography Thesaurus (CIT) Vocabulary

Through annotating this sample collection, we will gain a deeper comprehension of the painted subjects within this digitised CEW collection. Consequently, we will create CEW annotations grounded in the CIT vocabulary but tailored to a more specific focus. Thematic classification not only enriches our understanding but also opens avenues for future in-depth research. For instance, we may be able to explore potential preferences for subject matters across different periods, shedding light on the regions of China that held Western clients’ greatest interest during this time. Moreover, we can investigate variations in style, colour, and subject matter within paintings of the same theme across different periods based on our labels.

Figure 11: the CEW Project annotation workflow on Zooniverse

This annotation process serves as the initial stride in our research team’s endeavour to delve deeper into the collection beyond digitisation. We look forward to uncovering fascinating discoveries from the CEW collection.

Further image analysis

The next phase of research consists of classification and image analysis, which employs digital humanities and machine learning methodologies. Initially, we harnessed deep learning models that had been trained to extract image features, coupled with clustering algorithms, to autonomously classify the entire set of 2,308 images. After some adjustments, our algorithm can now broadly differentiate key image categories, such as figures, flora and fauna, and scenes. Specifically, the distinct framework of the five major subject categories led to nuanced algorithmic variations for each (see Figure 12 and Figure 13). Nevertheless, the presence of colour disparities, textual elements, and frame decorations poses challenges, hindering precise subject classification, particularly in images with subtle distinctions. At this juncture, manual intervention becomes imperative to rectify the categories of these images and subdivide them into finer sub-categories. The official nomenclature for these categories will undergo further refinement in subsequent publications.

Figure 12: The image clustering result in t-SNE visualisation (test result)

Figure 13: The sample of clustering images result (test result)

In our latest work-in-progress report, we have successfully identified a minimum of five major subject categories and 23 sub-themes within the Chinese export watercolours collection at the V&A Museum (as Figure 14).

Figure 14: five major themes and their number of paintings within the Chinese export watercolours collection at the V&A Museum

Topography and Architecture 地貌与建筑(91)

- Topographical views 地貌 (7)

- Interior scenes 室内场景 (52)

- Gardens 园林 (30)

- Shopfronts 店面 (2)

Manner and Customs 风俗习惯(304)

- Religious, Historical and Legendary characters 宗教、历史和传奇人物 (147)

- Pageants, processions, ceremonies, etc. 盛典、游行、仪式等 (49)

- Court of Justice 法庭 (3)

- Punishments and Tortures 刑罚 (48)

- Playing Boys 童戏 (48)

Occupations and Trades 阶层与行业(1076)

- Silk, Tea, Porcelain manufacture 丝绸、茶叶和瓷器制造 (118)

- Scenes of Daily Life 百业 (695)

- Dignitaries 权贵显要 (179)

- Warriors 武将士兵 (37)

- Women Playing Music奏乐 (47)

Flora and Fauna 动植物(438)

- Plant 植物 (312)

- Baskets of flowers 篮花 (22)

- Birds and flowers 花鸟 (36)

- Flowers and Insects 草虫 (56)

- Animals 动物

- Fish 鱼 (12)

Miscellaneous 其它 (338)

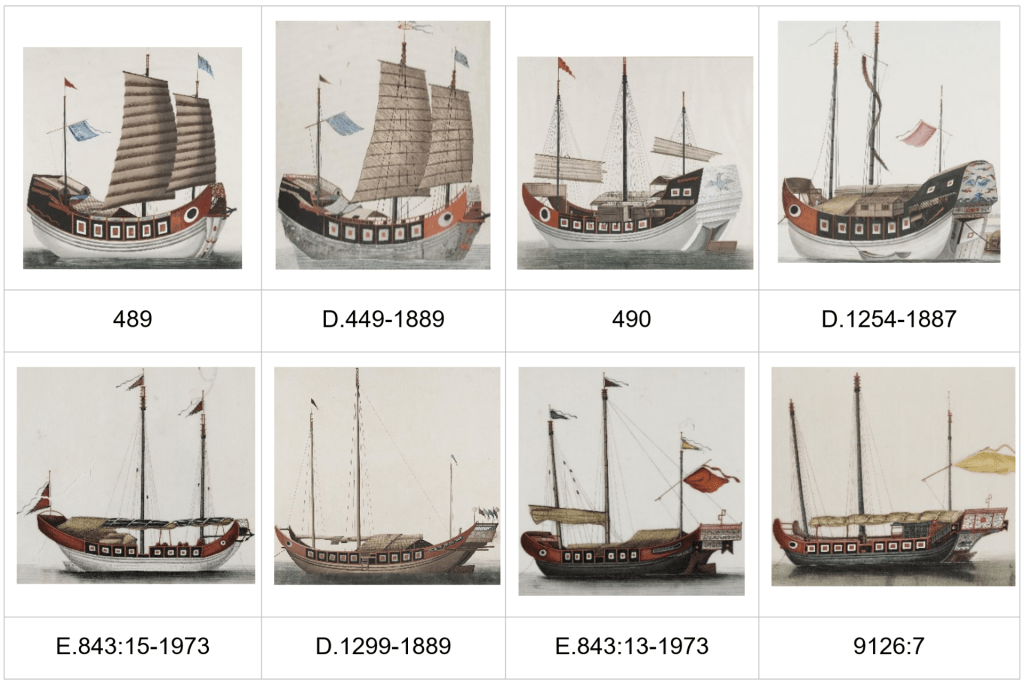

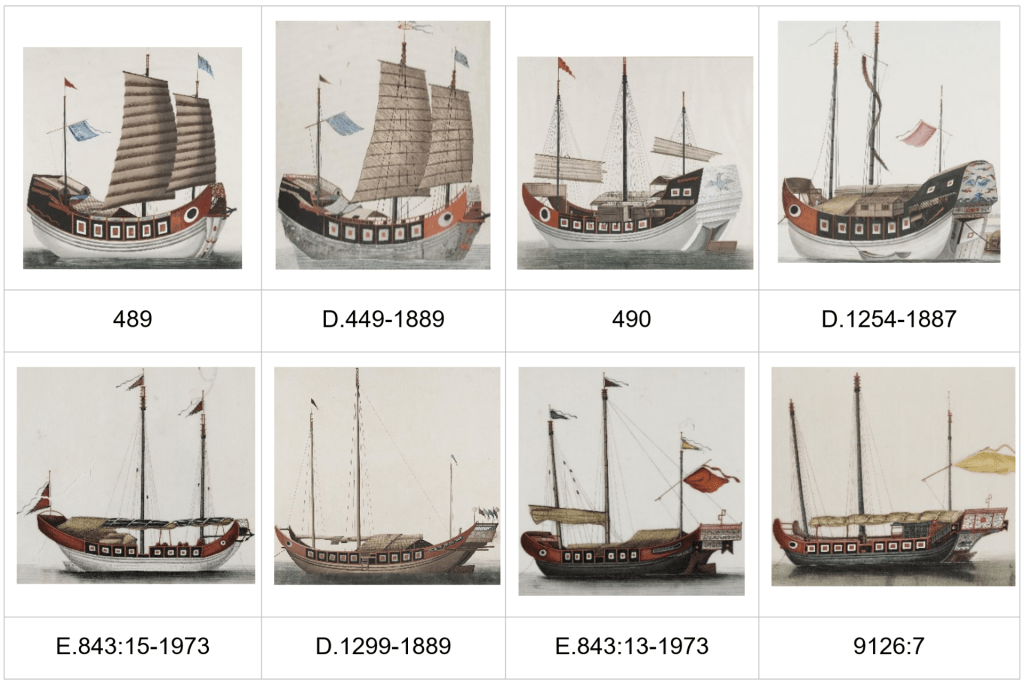

- Ships 船舶 (159)

- Furniture, shop signs, and Tools and utensils 各类器具 (179)

* Covers (18)

To engage in advanced image analysis, a profound comprehension of digitised images is a fundamental prerequisite, and it is rooted in the earlier stages of pre-photography, photography, and post-production, complemented by careful observation and documentation. Distinct image categories necessitate unique analytical approaches. Taking the sitting position of women and shouldering position of men as examples, images centred on human subjects primarily draw attention to facial features and the image wireframe of body poses (see Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 15: Image processing of the sitting position of women across different sub-categories for similarity analysis, especially the facial features and body poses © Victoria and Albert Museum

In a given set, numerous images may portray individuals in diverse situations, but some are with similar facial features and body poses. Similarly, there may be instances where different individuals wear remarkably similar clothing but in varying colours. The initial step in such analysis involves segmenting the image into recognisable sections, and by utilising feature extraction techniques, intrinsic characteristics and outlines are derived from these segments (Barthel et al., 2019). Subsequently, these images are collectively compared, and by employing such methodologies to analyse image similarity, it significantly enhances the efficiency of subsequent research and data analysis.

Figure 16: Image processing of Shouldering load with a pole in Scenes of Daily Life 市井百态 (695) for similarity analysis, especially the wireframe patterns of the human poses © Victoria and Albert Museum

Another category deserving attention pertains to Ships 船舶 (159) sub-category. In this context, the emphasis on similarity analysis primarily revolves around colour assessment and the evaluation of the overall image outline (see Figure 17). For these types of images, there is often no need to segment and compare individual components. Instead, a comprehensive approach is adopted, focusing on the overall similarity of the entire image. Additionally, there are various image analysis algorithms employed for assessing inter-image similarities, with subtle adjustments made based on the specific features of the images in question, all geared toward ensuring data analysis accuracy (Bengamra et al., 2023).

Figure 17: Image processing of Ships 船舶 (159) for similarity analysis, especially the patterns of boats © Victoria and Albert Museum

In addition, the category of Birds and flowers 花鸟 (36) presents an interesting case, especially when considering the consistent presence of both elements within the paintings (See Figure 18). The recurring motif of pairing birds with flowers carries multifaceted cultural and social meanings deeply rooted in Chinese artistic heritage, drawing on the association of flora and fauna with auspicious meanings and scholarly virtues that dates back centuries, and it also reflects on the CIT terminology (i.e., CIT0284614 花鳥 Birds and Flowers). The correlation between birds and flowers in the CEW collection opens up a fascinating avenue for further in-depth image analysis and cultural interpretation.

Figure 18: Image processing of Birds and flowers 花鸟 (36) for similarity analysis, especially the combination of flora and fauna © Victoria and Albert Museum

In general, the analytical techniques utilised in the CEW project provide invaluable insights, forming a solid foundation not only for the ongoing study of the CEW project but also for other subsequent research in the future. These findings deepen our understandings of the subject matter and also open up new endeavours for exploration and discovery. As we move forward, more project updates will be anticipated.

References

Barthel, K.U., Hezel, N., Schall, K., Jung, K., 2019. Real-Time Visual Navigation in Huge Image Sets Using Similarity Graphs, in: Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia. Presented at the MM ’19: The 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, ACM, Nice France, pp. 2202–2204. https://doi.org/10.1145/3343031.3350599

Bengamra, S., Mzoughi, O., Bigand, A., Zagrouba, E., 2023. A comprehensive survey on object detection in Visual Art: taxonomy and challenge. Multimed Tools Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-15968-9

Clunas, C., 1984. Chinese export watercolours, Far Eastern series. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Simpson, R., Page, K.R., De Roure, D., 2014. Zooniverse: observing the world’s largest citizen science platform, in: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on World Wide Web. Presented at the WWW ’14: 23rd International World Wide Web Conference, ACM, Seoul Korea, pp. 1049–1054. https://doi.org/10.1145/2567948.2579215

V&A, 2016. Chinese Iconography Thesaurus (CIT) · V&A [WWW Document]. Victoria and Albert Museum. URL https://www.vam.ac.uk/research/projects/chinese-iconography-thesaurus-cit (accessed 9.1.23).

Close

Close