Recall petitions: process, consequences, and potential reforms

By Rowan Hall, on 11 December 2023

A recall petition is currently open in Wellingborough, which could lead to MP Peter Bone being recalled by his constituents, followed by a by-election. This is the fifth such petition in as many years. Tom Fleming outlines how the UK’s recall system works, summarises its effects to date, and outlines possible areas for reform.

How do recall petitions work in the UK?

A system for ‘recalling’ MPs was first introduced in the UK by the Recall of MPs Act 2015, which came into force in March 2016. This legislation was introduced by the Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government, following commitments to some kind of recall procedure in both parties’ 2010 election manifestos.

In short, recall is a process by which voters are empowered to remove (i.e. ‘recall’) their MP prior to a general election if they are found to have committed certain types of serious wrongdoing.

Under section 1 of the 2015 Act, the recall process is triggered whenever an MP meets one of three conditions:

- receiving a criminal conviction that leads to a custodial sentence (though sentences of more than a year already lead to disqualification from being an MP, under the Representation of the People Act 1981),

- being suspended from the House of Commons for at least 10 sitting days (or two weeks) after a report from the Committee on Standards (or another committee with a similar remit), or

- being convicted of making false or misleading expenses claims under the Parliamentary Standards Act 2009.

If any of these conditions is met, a recall petition is opened for six weeks in the affected MP’s constituency. If 10% of registered voters sign the petition by the deadline, the seat is declared vacant, and a by-election is held to elect a new MP (though the recalled MP remains free to stand again as a candidate). If the petition fails to reach the 10% threshold, no by-election is held and the MP retains their seat.

(more…) Close

Close

With just two weeks until polling day, the major parties have all published their manifestos: we now know their stated plans for the constitution. Stephen Mitchell, Elspeth Nicholson, Harrison Shaylor and Alex Walker examine what each party has to say about constitutional reform of the UK’s institutions, altering the devolution settlement and developing a written constitution.

With just two weeks until polling day, the major parties have all published their manifestos: we now know their stated plans for the constitution. Stephen Mitchell, Elspeth Nicholson, Harrison Shaylor and Alex Walker examine what each party has to say about constitutional reform of the UK’s institutions, altering the devolution settlement and developing a written constitution. In March, Sir David Natzler retired as Clerk of the Commons after over 40 years in the House. Now, he is the co-editor of Erskine May, the 25th edition of which is the first new edition in eight years, and is

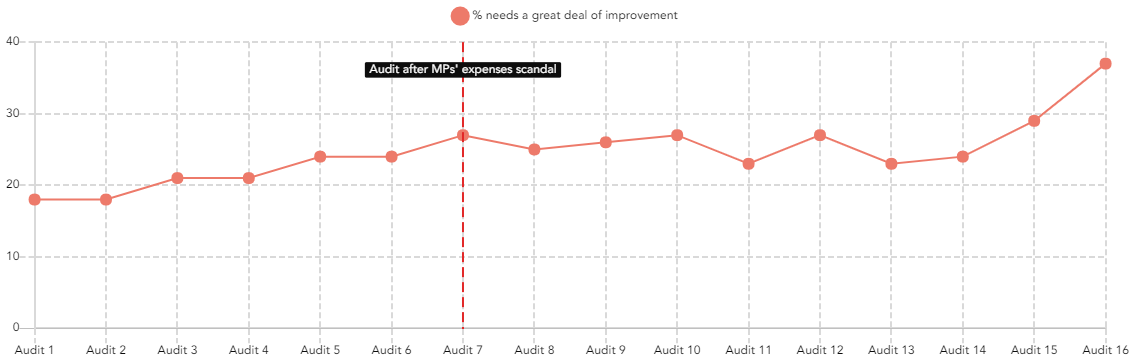

In March, Sir David Natzler retired as Clerk of the Commons after over 40 years in the House. Now, he is the co-editor of Erskine May, the 25th edition of which is the first new edition in eight years, and is  Each year, the Hansard Society conducts an

Each year, the Hansard Society conducts an