STUDENT BLOG #2 | Gender Equality Stream | June 11, 2017

By Veronique L. Porter

The Hair, Skin, and Education of Black Girls

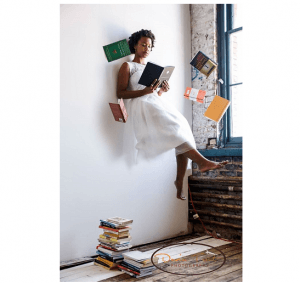

Photo credit Devin Trent

I wrote this blog post in high anticipation of the Centre for Education and International Development (CEID) symposium on June 15th, and the discussions to follow around the CEID’s thematic areas including gender equality and women’s rights.

As I struggled to write this blog post, my classmate suggested I write about something I am passionate about. She is familiar with my social media, and knows my interests run wide and deep from my various posts. While my interests range across many areas, subjects, and themes, people of color are at the center. As an Education, Gender, and International Development student at UCL’s Institute of Education, right now I am keen to take a deeper look at Black girl’s education.

Despite my formal and informal studies and my life long experience, I somehow felt underqualified as I began to write. This is not an unfamiliar or irrational feeling. Rather it’s a response to subtle and obvious conditioning that my kinky hair and dark skin are not the features associated with educated, qualified people. And this reaction is not my unique struggle.

Black girls get these cues every day, often within the school environment. Schools in the United States often punish and suspend Black girls for being loud and aggressive at much higher rates than their peers, consistent with the perception of dark skinned women being angry and defiant. One ten-year-old student in the United States faced bullying at two schools over her dark complexion. To make matters worse, her teacher handed her a black crayon, instead of a brown one, during an assignment to draw self-portraits.

On an institutional level, many school policies regulate Black hair. Another US student was told her textured hair was “out of control and all over the place.” She was threatened with expulsion from the school if her hair was not “fixed or styled,” as her textured hair was considered a fad, which is against school policy. A school in South Africa told a student that she could not take her exams if she did not straighten her hair or make it “more beautiful.” A Black university student was barred from entering the university building in Brazil, because her “Black Power” hairstyle was too political. These are not policies that restrict styles but the texture as it naturally grows from these students’ heads.

The instances mentioned above are only a few examples of the intolerance that Black girls face based on their physical features. Stories like these regularly appear on news websites, in the content podcasts and blogs, and in my social media feeds, usually from sources that purposefully include Black news, events, and culture. The prevalence of these policies send clear messages to Black girls that they are not welcome in the learning environment without altering themselves. They should have a docile demeanor and be sure not to voice their opinion for fear of being perceived as being disruptive or defying authority. Highly textured hair needs to be altered for the classroom otherwise it is distracting or unkempt.

I say “Black” knowing that this is a very American way to label dark skinned people. Yet this is the most authentic way for me to describe the common denominator of the groups of people identified by their dark skin, and who face various types of oppression and discrimination in communities all over the world on the basis of their dark complexion.

My feelings of inadequacy, while sometimes frequent, are often brief. I know that I am knowledgeable and equally capable as my peers from other nationalities and of other complexions. But Black girls all over the world are shaping their personalities, their lives, their futures based on the information we give them in society and especially in school. There should not be an association with students’ physical characteristics and their learning. Schools can create and reinforce standards that make it more difficult for Black girls to learn by making them uncomfortable in their own bodies. But schools can also create a setting that values learning over appearance. The first step in creating a welcoming and equitable learning environment in schools is to allow Black girls to be Black students and eliminate policies that target their innate features.

I am looking forward to the ways the new Centre for Education and International Development (CEID) gender equality and women’s rights will contribute to girls’ education for girls of all backgrounds, ethnicities, and nationalities. But selfishly, I want more focus on the education of Black girls, so the Black girls of tomorrow don’t have to face the same oppression and inequality as the Black girls of today. I hope to discuss this topic more with my classmates and education experts during the CEID launch event, Thursday, June 15th.

Written by: Veronique L. Porter

Veronique has years of professional experience working in West Africa on education, youth development, and health, and supporting various USAID development programming from Washington, DC. At the time of writing, Veronique is studying the MA in Education, Gender and International Development (EGID) at the IOE.

Close

Close