Alternative Histories of Education and International Development #004 – Unterhalter

By utnvmab, on 11 January 2021

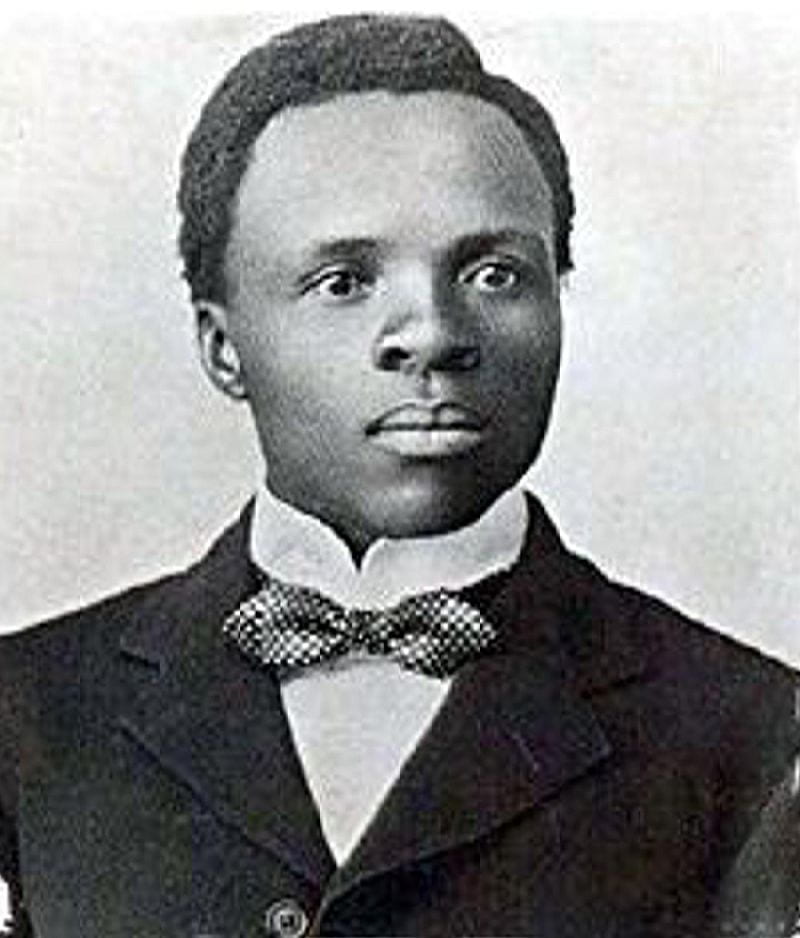

Sol Plaatje and UCL

Sol Plaatje and UCL

Sol Plaatje’s name is probably unknown to all but a handful of people at UCL. Yet his scholarship in his lifetime, was partly linked with UCL, and his scholarly legacy is highly significant for thinking about education and international development as a field of inquiry.

Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje (1876-1932) was a South African whose whole life was an engagement with different aspects of education and a negotiation with what we call today international development, but what was, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, framed by Empire and colonial relationships . Sol Plaatje was born in 1876 in what is today the Free State province of South Africa. Educated by German missionaries he was fluent in Setswana, English, Dutch, and four other languages. He worked as a teacher, a telegraph messenger, a clerk, a court interpreter, a journalist, newspaper owner, editor, a translator, a researcher, a political organiser and lobbyist, a negotiator, an actor, a singer, a novelist and an academic researcher. His life story brims with so many incidents, and highlights so many different kinds of educational relationships in South Africa, England and the USA, that it is a clear education and international development can never be only about one kind of formation of human capital, a single kind of accumulation of social capital or a one-dimensional form of subordination to colonial rule.

Plaatje was immersed in, but always critically engaged with, colonial cultures. His dialogues, disputes, and demands came through his religion, his education, his nuanced responses, for example with translating and performing Shakespeare, or writing political commentaries to be read by colonial rulers and their critics. But, for all his dress and bearing in the style of a Victorian and Edwardian gentleman, he was also, keenly aware of the dispossessions colonial relations brought – the denial of the vote to the majority of people in South Africa, the dispossession of land rights that had been established under Colonial law, and the ways in which the experience of colonial subjects, viewed primarily in terms of their race, were overlooked in what was documented and published about South Africa. He wrote about much of this in his widely circulated book Native Life in South Africa , published in 1916, which generated much discussion when it first came out and continues to excite debate. He was a founding member of the SANNC (South African Native National Congress), which became the ANC. His contribution to literature, art and politics has now been acknowledged in South Africa and beyond.

For us at UCL there is a particular connection with Plaatje’s life and intellectual contribution. During a stay in London in 1916 Plaatje met Daniel Jones, who was the Head of the Department of Phonetics at UCL. Plaatje had come by sea from South Africa, with a delegation of South African political leaders, to draw to the attention of the Colonial Office the devastating effects of the 1913 Land Act, which had dispossessed African landowners in South Africa. The delegation was not successful and most members returned home. Plaatje remained in London, meeting people who shared some of his many interests. These included the writers Alice Werner and Olive Schreiner ,and the publisher, Victor Gollancz. He participated in some of Jones’ classes at UCL, explaining Setswana to seminar groups working on phonetics. Jones co-authored with Plaatje A Sechuana Reader in 1916. This was an account of how a tonal African language worked. Jones also drew on Plaatje’s in depth knowledge of language for his article ‘The phonetic structure of the Sechuana language’, published in 1917. In this article Jones became the first writer to use the term ‘phoneme’ to denote distinct sounds in a language. Given how influential, the identification of phonemes have become , and their significance in the teaching of early reading through the system of phonics, this is an under remarked collaboration that needs fuller acknowledgement.

Today debates around the teaching of reading have one strand which debates whether it is more important for learners to know sounds (phonemes) that help develop skill in reading or to appreciate the stories, that nurture an interest in what stories have to say. These lines of discussion were trailed between Plaatje and Jones. Plaatje located his discussion of the phonetic structure of Setswana in relation to telling stories and recounting proverbs. His desire to foster knowledge of the history and culture of the people he grew up with is expressed in the novel he wrote, Mhudi. Published after his death, this was the first novel written by a black South African. In The Preface to Mhudi Plaatje noted, ‘South African literature has hitherto been almost exclusively European’. He went on to explain that he had written Mhudi ‘with two objects in view, viz. (a) to interpret to the reading public one phase of “the back of the Native mind”; and (b) … to collect and print Sechuana folk-tales, which, with the spread of European ideas, are fast being forgotten’. He hoped, in this way, ‘to arrest this process by cultivating a love for art’.

Plaatje was part of a network of writers in South Africa and across the Empire, brought up and shaped by a form of qualified inclusion, associated with colonial education, religion and culture. But this form of inclusion was also profoundly excluding, as Plaatje noted in some of his works, and the Preface of Mhudi makes clear. Plaatje’s association with UCL has features of this exclusion. Daniel Jones became a Professor at UCL. Plaatje had no formal higher education and worked at any number of short term jobs. While some of his writings, including the collaborative work of scholarship he wrote with Jones, were published in his lifetime, others remained unknown. The extent, range and significance of his work has come to light mainly through scholarship over the last 40 years.

There is much we can learn in CEID from this history. Clearly issues remain regarding questions of authorship and whose ideas are given acknowledgement, and whose overlooked. In addition there are many further issues with regard to method, the location of education, and the history of our field.

One of the proverbs recorded in the Sechua Reader of 1916 was ‘Alone I am not a man; I am only a man by the help of others’. There is a clear line from this proverb to contemporary discussions in education and international development of ubuntu, a philosophy of society and education as a form of enacting solidarity, recognizing that one is only a complete person through others. There are also links to some of the discussions of decoloniality. There is much to learn about forms of colonialism and education in Plaatje’s writings and his life, noting the many obstacles established by colonialism and racism and other intersecting inequalities Education and international development has become a field of inquiry partly through the experiences Plaatje bore witness to. In addition Sol Plaatje’s contribution to the history of linguistic scholarship, in my view, needs to be noted and credit given for his pioneering work, even though it is more than 100 years late. . UCL is considering renaming some of its buildings andIit seems fitting Sol Plaatje’s name should be recorded on one of them.

Refernces

Plaatje, S. 1916 Native Life in South Africa London: King & Son

Plaatje, S. 1930, Mhudi, Lovedale Press: Lovedale Press

Willan, B., 2018, Sol Plaatje. A life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, 1876-1932 Johannesburg: Jacana

Peterson, B. Willan, B. and Remmington , J. eds. 2016, Sol Plaatje’s Native Life in South Africa. Past and Present Johannesburg: Wits University Press

Sound recordings of Sol Plaatje held by the British Library: http://sami.bl.uk/uhtbin/cgisirsi/?ps=oQFhH0dmMa/WORKS-FILE/1820047/123

Opinions expressed on the CEID Blog are only those of the author, not the Centre for Education and International Development or the UCL Institute of Education.

Want to publish a blog post in this series? Send a submission or idea to: Mai Abu Moghli or Charlotte Nussey.

Close

Close