Tower House (former Rowton House), 81 Fieldgate Street, Whitechapel

By the Survey of London, on 28 September 2018

With its distinctive roofline and seven storeys rising sixty feet, Tower House is a local landmark that did indeed tower above its neighbours when first built. Initially called Rowton House, Whitechapel, the building opened in 1902 and was the fifth of six ‘Rowton Houses’ established in London between 1892 and 1905 to provide decent, low-cost accommodation for single working men. Known as Tower House from 1961, during the late 1970s the building was found to be inadequate as housing and began to decline. After various schemes to adapt it for use as a public building and supported housing fell through, Tower House was sold to a developer and converted to upmarket apartments in 2005–8.

Tower House, Fieldgate Street, view from the southwest in 2016. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Rowton Houses were large model lodging houses founded by Montagu (‘Monty’) Lowry Corry, later Lord Rowton (1838–1903), Tory politician, nephew of the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, and former secretary to the Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli. Rowton was appointed Chairman, the other founding directors being Cecil Ashley, Richard Farrant and Walter Long, MP and former Chairman of the Local Government Board; after accepting a Cabinet post, Long was replaced by William Morris (junior), a partner in the firm of Ashurst Morris Crisp, which acted as the company’s solicitors.

Rowton House, Whitechapel from the east, c.1903. (From Jack London, The People of the Abyss, 1903)

Known as ‘hotels for working men’, the buildings were a response to the capital’s housing crisis of the 1880s, intended as superior alternatives to the common lodging house, where the poorest Londoners slept in dormitories over a shared kitchen. Like other kinds of model housing, Rowton Houses were intended to be models of hygiene and order, and as models for other organisations to follow. Rather than being purely charitable institutions, they were designed to turn a modest profit for shareholders, on the model of five per cent or ‘remunerative’ philanthropy. The local and national press, and medical, architectural, sanitary, and municipal journals were broadly supportive of the Houses’ improving aims and reported on them at length.

Rowton Houses were not intended to be the cheapest lodgings. Common lodging houses cost from around 4d per night in London at this time and the London County Council (LCC) initially charged 5d at its municipal lodging house. Rowton Houses insisted that their enterprises were not charitable or philanthropic organisations but poor men’s clubs or hotels. At the opening of the Whitechapel House, the chairman, Richard Farrant, was reported as saying privately that ‘the Carlton and Reform Clubs might have superior upholstery but that there was not a club in London where a man could live so comfortably, economically, and healthily as at the Rowton Houses’. [1] The press made frequent approving comparisons with gentlemen’s clubs and, in many ways, including the exclusion of women, the suites of dayrooms and the encouragement of male sociability, Rowton Houses did resemble all-male elite clubs.

The first Rowton House opened at Vauxhall in 1892 (470 cubicles). King’s Cross opened in 1896 (677), Newington Butts in 1897 (805), Hammersmith in 1899 (800), Whitechapel in 1902 (816) and Camden Town (Arlington House) in 1905 (1,087). The architect for all apart from Vauxhall was Harry Bell Measures, whose characteristic red-brick blocks lined with slit windows, leavened with gables, turrets and terracotta detailing, created a new and easily recognisable style of building in the capital. Of the five London Rowton Houses designed by Measures, only Tower House and Arlington House survive and only Arlington remains in use as a hostel.

The Whitechapel building was made up of two adjoining parallelograms separated by an inner courtyard open at one end, in order to provide good air circulation and light. On concrete-clad steel construction, the elevations are in pressed Leicester facing bricks, with Fletton bricks on inward faces. Semi-circular windows face outwards from the dayrooms on the first two floors, including in the two bays at this level (one of which has been replaced by a new entrance), and above these are the rows of narrow windows to the hundreds of cubicles, the sashes and frames to which have been replaced throughout the building. Externally, the expanse of brick is relieved with gables, turrets and pink terracotta dressings, and the large projecting porch, flanked with octagonal finials, and which served as the original entrance, is also of terracotta. The diminutive cherub presently seated on the central finial is a recent addition; it replaced a larger figure of a child holding a globe on his shoulders, which may have represented a young Atlas.

Original entrance porch at Tower House, 2016. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

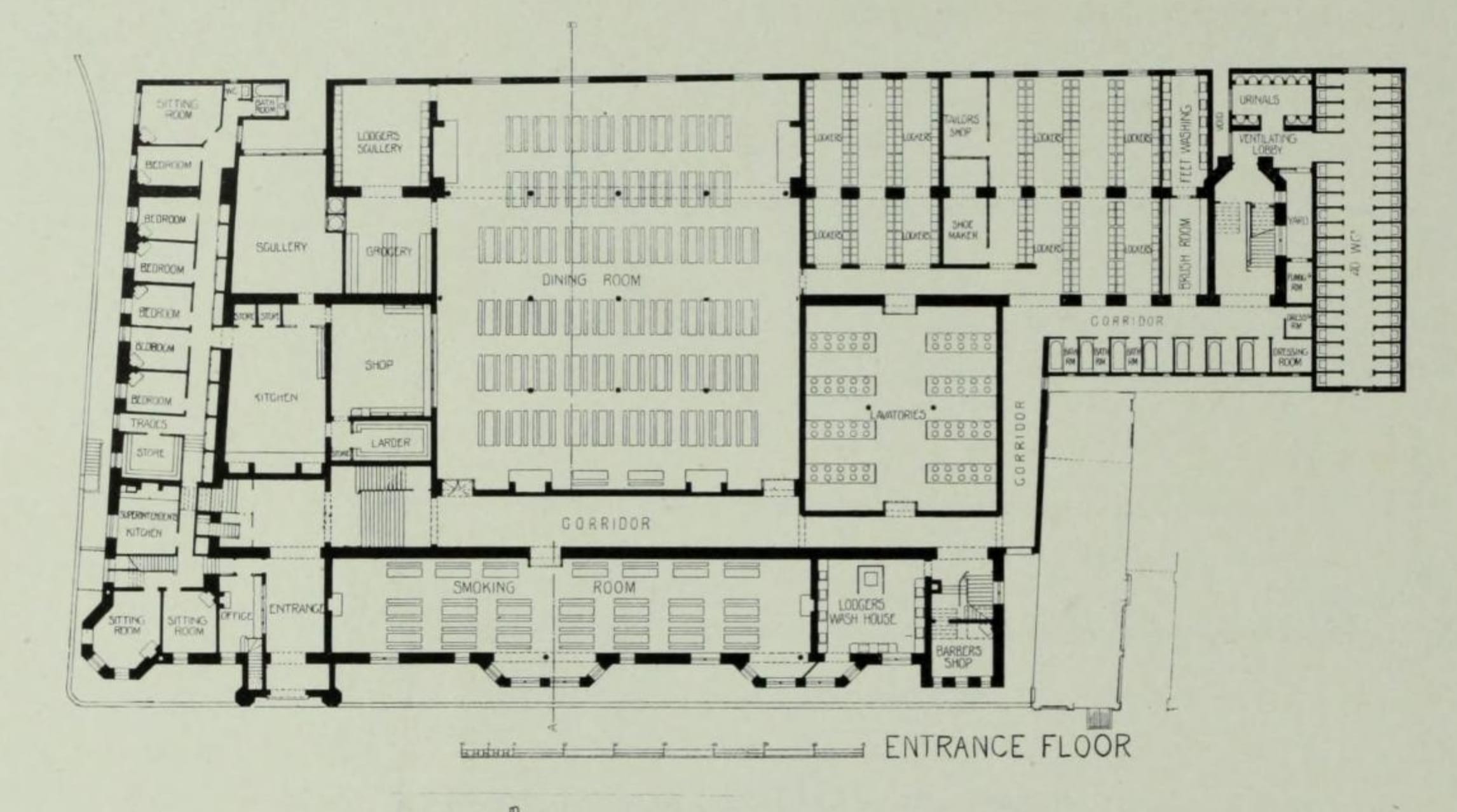

Originally the first two floors (known as the ‘entrance floor’ and, above that, the ‘ground floor’) contained the office, staff quarters, and the lodgers’ kitchen, dining and other dayrooms, washing facilities, lockers and services; above these were five floors of cubicles, whose rows of narrow windows contributed to the building’s outwardly institutional appearance. When Measures was asked why he didn’t group his windows, he replied that ‘if I yield to that temptation, then the sleeper has to pay the penalty for the sake of my elevation. Personally, I think the sleeper comes first and that my elevations should truthfully proclaim it’. [2] Despite the new entrance and alterations to the windows made as part of the 2005–8 conversion, the Fieldgate Street elevation still reads as a Rowton House, the major alterations to the exterior being the penthouse floor and at the rear of the building.

On entering Rowton House, Whitechapel, lodgers bought a ticket at the office window and, if they wished, weekly lodgers could pay a 6d deposit for a locker, before passing through a turnstile and into a vestibule. From here, lodgers could go up a flight of stairs to a small ‘glass-roofed lounge with palms and flowers’. [3] Or they could enter the main corridor, on the lower ground ‘entrance floor’, which ran east–west through the building. The lockers, and the sinks, baths and footbaths (free), baths (1d including soap and towel) and facilities for washing and drying clothes, were all located on the east side of this floor. The tailor, shoemender and barber were in the same area. Once clean and dressed, the men could go to their cubicle for the night or make use of the dining and recreation rooms up to a certain time in the evening.

Rowton House, Whitechapel, plan of the entrance floor, from The Brickbuilder, July 1903. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California) Please click on the image to view a larger version.

A huge dining room occupied the centre of the entrance floor, with seating at teak tables for 456 men. Lodgers could cook their own suppers over a range, either with food they brought with them or from ingredients bought at the shop. Alternatively, they could buy a cooked meal at prices which, as the company stressed, amounted to little above cost, achieved through the bulk buying of provisions. Lodgers could purchase a pint of tea in a special Rowton House-emblazoned mug for a penny in 1906, while 5d bought a plate of roast mutton or beef with seasonal vegetables followed by a hot pudding. Top-lit and ventilated with lantern lights, the dining room was finished with the same ‘high dado of glazed brickwork in tints of cream and chocolate’, as found throughout the dayrooms. [4] Due to the size and function of the building, institutional associations were impossible to escape but the aim was to mitigate this through dayroom arrangements and decoration and, at Fieldgate Street, to ‘give an effect of sprightliness and comfort’. [5] Framed pictures hung on the walls, the plastering ‘tinted to a shade of terracotta’ above the tiling.[6] While Measures was responsible for the design of the building, Rowton and Farrant personally oversaw the interior design and decoration, choosing the bedding, furniture, pictures and, even, at King’s Cross, a stag’s head shot by Rowton, for the walls.

Rowton House, Whitechapel, dining room, from The Brickbuilder, July 1903. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California)

On the south side of the corridor on the entrance floor lay the smaller smoking room, its windows in the central bays looking, through the railings, into Fieldgate Street. This had space for 140 lodgers at teak tables with additional easy chairs around the fire places at each end. Cards and games of chance which might encourage gambling were banned but chess and draughts were provided.

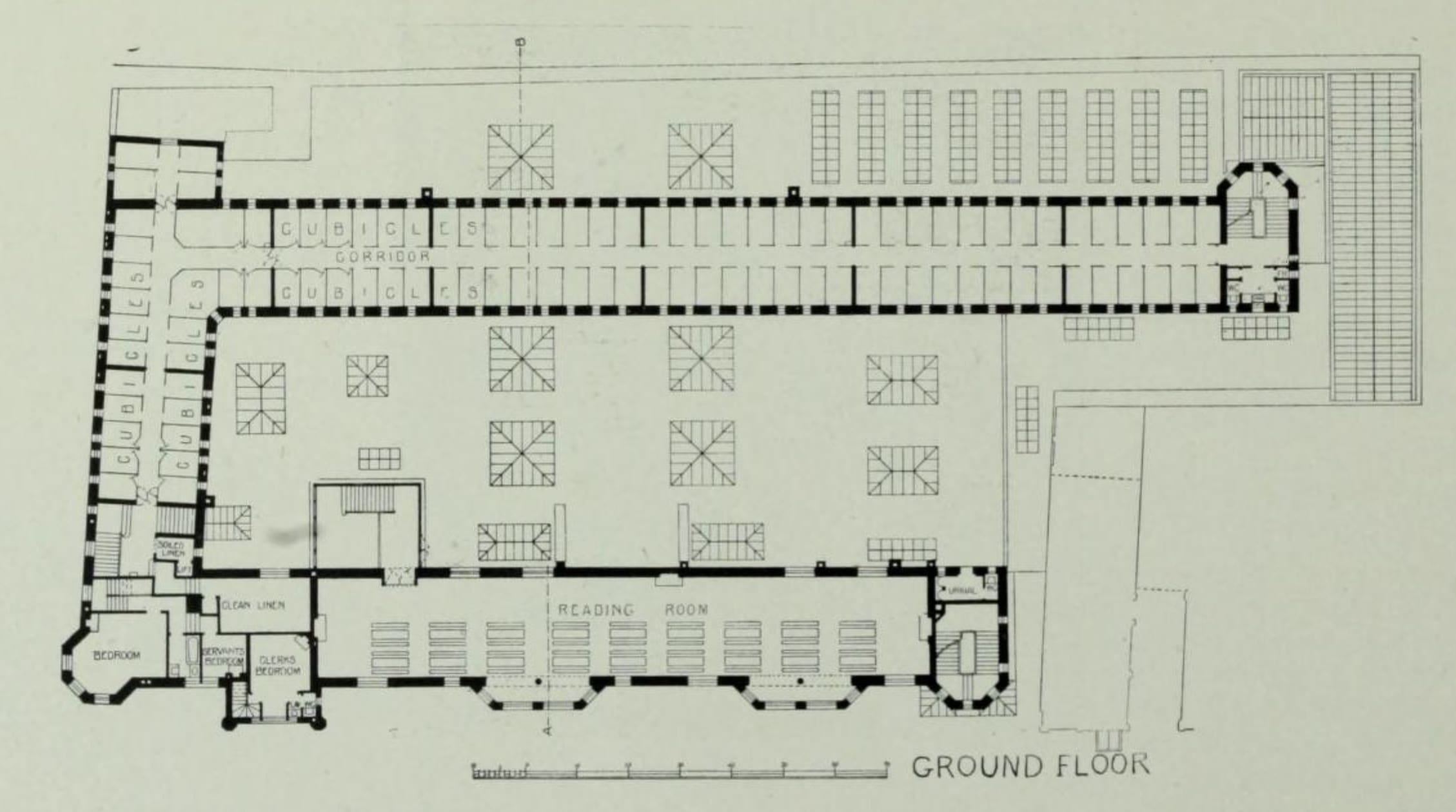

The reading room lay immediately above the smoking room on what was known as the (upper) ground floor. This was fitted with cupboards for newspapers and bookcases, from which lodgers could borrow books on application to the Superintendent, open bookcases having been abandoned across the Houses after thefts made it necessary to lock them.

Rowton House, Whitechapel, plan of the ‘ground’ (first) floor, from The Brickbuilder, July 1903. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California) Please click on the image to view a larger version.

A series of panels ‘emblematic of “the Seasons”’ hung in the reading room. These took up a large part of the back wall facing the windows onto Fieldgate Street, fitted above the tiling. As was widely reported, these were ‘painted by Mr H. F. Strachey of Clutton, near Bristol, a cousin of Lytton Strachey and art critic of The Spectator. They were given by him as the practical interest of an artist in the elevating work of a Rowton House’. [7] ‘Each season is represented by a single figure and also by a larger composition, while over the fireplace in the middle is a small allegorical work. In it a symbolical figure of England sits enthroned, while the fruits of the land are brought to her by the cultivators’. [8]

There were no panels in the other Rowton Houses and it is not known what happened to those at Fieldgate Street. It is possible that they were lost during alterations of 1953, which divided the Reading Room into a Billiard Room and a Quiet Room.

Near the reading room was a door to the open-air or smoking lounge. As at the previous Rowton Houses, this was formed on the roofs of the rooms below, in this case the kitchen, dining and washroom areas. Invisible from the street, this space, in the void which allowed air and light to circulate within the building, was fifty feet wide and surrounded on three sides by the cubicle floors. Benches were placed around the lantern lights and it was laid out with tubs of flowers as a roof garden. Like the decoration, pictures and pot plants within the House, the garden was an attempt to de-institutionalise the buildings.

Rowton Houses prided themselves on the superior size and construction of their cubicles and on the quality of the beds and bedding. After experiments with shared dormitories at Vauxhall proved unpopular, all subsequent Houses were provided with individual sleeping cubicles. These measured 5ft by 7ft 6inches and were 9ft high. Each lodger had a sash window under his own control, an iron bedstead with a sprung mattress, a clothes hook, and a chair. The partitions (of strong pine, rather than iron as in shelters and some model lodging houses) reached nearly to the ceiling, with a space at the top. Initially this was left open but in the early twentieth century was meshed in after ‘fishing’ by residents into neighbouring cubicles showed that valuables were unsafe. By this means visual privacy was achieved while ensuring the building remained light and well ventilated.

Rowton House, Whitechapel, footbaths, a cubicle and corridor, from The Brickbuilder, July 1903. (Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California) Please click on the image to view a larger version.

This account is extracted from a fuller history by Dr Rebecca Preston for the Survey of London (link). That draws on the project, At Home in the Institution? Asylum, School and Lodging House Interiors in London and South-East England, 1845–1914, led by Jane Hamlett at Royal Holloway, University of London, in 2010–11, and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (RES-061-25-0389).

[1] Yorkshire Post, 7 August 1902, p.6.

[2] British Architect, 22 March 1901, p.213.

[3] Yorkshire Post, 7 August 1902, p.6.

[4] East London Observer, 9 August 1902, p. 8

[5] London Evening Standard, 7 August 1902, p.7.

[6] East London Observer, 9 August 1902, p.8.

6 Responses to “Tower House (former Rowton House), 81 Fieldgate Street, Whitechapel”

- 1

-

2

Survey of London wrote on 30 September 2018:

Thank you for your comment. That’s correct, the Vauxhall Rowton House does still stand. It was the first to be built, and was designed by W. F. Beeston. It wasn’t mentioned in that sentence only because it wasn’t one of the five designed by Measures.

- 3

-

4

Survey of London wrote on 15 May 2021:

Dear John

Sincere apologies for our slowness in picking up your message. The short answer is that I don’t know. All that we know about Tower House can be read here – https://surveyoflondon.org/map/feature/839/detail/#tower-house-former-rowton-house-81-fieldgate-street

kind regards

Peter Guillery -

5

Peter Kennedy wrote on 24 April 2022:

I stayed at tower house most of 1973/1974 the cubicle was small (two arms fully extended and fingers outstretched touched each wall wide) warm in winter, the bed was clean crisp white sheets with a heaviest candlewick bedspread over a grey warm woolen blanket. there was a long narrow window. all the young guy were lodged at the top of the house lots of stairs to climb, it cost 50p a night or 5 quid for the week, it was always wise to book your room the first thing in the morning or you might lose out for a room if you were paying by the day, a guy used to walk the corridors in the morning ringing a bell each cubicle had its own key which had to be handed in in the morning and taken back if you were re-booking. so you could leave you baggage in the room safely enough, there were also specials these rooms were much bigger about 12 foot square for longer term residents if wanted, there were also baths with really high quality towels etc. the food left a lot to be desired was not really my taste heavy soups sometimes stews winter and summer but at a very cheap price just 10p or so. I met a lot of characters there most were alcoholics but many were men who were divorced men down in their luck and many moved on. these houses were a blessing for people who would have been sleeping in the streets, were one could eat sleep keep warm and get cleaned up until you could move on again. They really were a Godsend.

-

6

Karen Whaley wrote on 24 April 2022:

I was the nurse in Tower House from 1986 to 1989 and met some wonderful men. Most of them had hard and extraordinary lives. I think of them often

Close

Close

“Of the five London Rowton Houses designed by Measures, only Tower House and Arlington House survive and only Arlington remains in use as a hostel.” The one at Vauxhall still stands and is in use by #Connexions for young people. I walked past it last May 2017.