Comparing the Differences in Early Warning Systems between Shanghai and Hong Kong: Exploring the Potential for Shanghai and Hong Kong to Improve Early Warning Systems

By Amanda Gallant, on 28 September 2023

By: Zhang, Yue

University of Glasgow

1. Introduction

As two of the most dynamic metropolises in Asia, Shanghai and Hong Kong face significant shared challenges when it comes to managing and mitigating the impacts of natural hazards. Both cities are positioned within regions characterized by heavy summer rainfall making them susceptible to threats such as flooding, typhoons, tropical cyclones, and storms, presenting constant challenges to their infrastructures and populations (State Council Information Office of PRC, n.d.; Michigan State University, n.d.).

Shanghai, strategically located on the Yangtze River Delta, is a city besieged by an array of meteorological hazards. Its low-lying coastal geography, with over half of the city sitting at or below sea level, heightens its vulnerability to phenomena such as storm surges and land subsidence (Zhao et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2022). Further challenges emerge from the city’s rapid urbanization and extensive paving, amplifying the risk of urban flooding during heavy rainfall events (Wang et al., 2020; Xu, 2020).

Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s geographic profile offers a stark contrast. Dominated by mountainous terrain, granite, and easily weathered rocks, along with uneven surface coverage, the city contends with the threat of landslides and flash floods (Chen et al., 2014). The steep inclines and concentrated developments in low-lying coastal areas heighten the city’s exposure to such hazards, particularly during the typhoon season. Furthermore, Hong Kong’s position on the map subjects it to frequent tropical cyclones, capable of causing severe wind damage and flooding (Chen et al., 2014).

Despite their shared regional characteristics and the common risks they face, the responses of Shanghai and Hong Kong to these challenges are far from identical. Each city has developed its own unique hazard warning and response systems, influenced by distinct historical, cultural, and political contexts. This blog will delve into the differences between Shanghai, a major city in mainland China, and Hong Kong, a Special Administrative Region operating under the “One Country, Two Systems” policy. It will explore the effectiveness of these varying approaches, consider their strengths and limitations, and investigate potential areas for mutual learning and improvement. By doing so, we hope to shed light on how these two iconic cities can enhance their resilience in the face of the ongoing threat posed by natural hazards.

2. Background – The History of Warning Systems in Hong Kong and Shanghai

2.1 Hong Kong’s Legacy of Warning Systems

The origins of Hong Kong’s warning systems can be traced back to the 19th century, a time when the city was frequently battered by typhoons. The “Jiaqing typhoon hazard of 1874” was among the most devastating events, triggering a wave of change in the region’s hazard management approach (Bian, 2020). To safeguard public safety, the Hong Kong government inaugurated the Hong Kong Observatory in 1883, which set the wheels in motion for regular meteorological observations. This institution also took the initiative to develop a tropical cyclone warning system utilizing visual signals and incorporated magnetic and astronomical observations into its suite of capabilities (Hong Kong Observatory, 2023).

Time Ball of Tsim Sha Tsui Police Station (1885-1907)

History of Hong Kong Observatory, 2023

Hong Kong’s economic boom between the 1950s and 1970s brought along an array of challenges. During this time, the city’s population doubled, leading to a surge in construction on steep hillsides. With houses being built without professional design or reinforcement, heavy rainfall resulted in frequent mudslides and landslides, transforming Hong Kong into a high-risk zone for such hazards (Keegan, 2022). The unstable mountainous terrain was particularly susceptible to rainwater-induced erosion. The escalating landslide threat took a severe toll on residents’ safety and properties, culminating in hazardous incidents like the Sau Mau Ping Landslide in 1972, which razed 78 squatter huts and claimed 71 lives (CEDD, 2021).

Sau Mau Ping landslide in 1972

(CEDD, 2021)

Reacting to the dire situation, the Hong Kong government established the Civil Engineering and Development Department (CEDD) in 1972 to curb the escalating landslide threat. The CEDD and the Hong Kong Observatory joined forces to issue warnings about potential landslides and flash floods. Fast forward to 2022, Hong Kong now enjoys the reputation of being the world’s first city to design and implement a slope safety system targeting landslide prevention, as reported by the BBC (Keegan, 2022). This government-driven initiative has significantly enhanced slope safety and mitigated landslide risks, setting a global standard in the process.

The period following Hong Kong’s reintegration with China in 1997 saw the region making significant strides in bolstering public safety. The government ramped up investments in the development of sophisticated, technology-driven warning systems. A major breakthrough occurred in September 2007 when the Security Bureau and Emergency Support Unit unveiled the “Natural Hazard Contingency Plan” at the Hong Kong Government Headquarters (Government Headquarters Security Bureau Emergency Support Unit, 2007). Characterized by its detailed division of labor, clear-cut responsibilities, and ease of implementation, this plan cast the Hong Kong Observatory in a pivotal role. The Observatory was tasked with closely monitoring weather conditions, swiftly issuing warnings to the media and relevant departments during adverse weather and providing timely weather updates.

The evolution of Hong Kong’s warning system illustrates the remarkable benefits of strategic investments in hazard prevention and management, which have considerably reduced casualties and property destruction. With its pioneering slope safety system and advanced warning mechanisms, Hong Kong offers a commendable model for international endeavors in hazards management.

2.2 Shanghai’s Meteorological Early Warning System

Shanghai’s meteorological early warning system carries a rich history, stretching back over a century. In 1884, the Shanghai Bund signal tower embarked on the journey of displaying regular meteorological signs, reflecting weather fluctuations to assist ships anchored in the Huangpu River. Flags or balls hoisted on the tower’s mast signaled imminent weather changes. If a typhoon were on the horizon, these signals would provide critical information on the typhoon’s strength, direction, and location, furnishing an early warning (PengPai news, 2022).

Figure 1: The Bund Observatory / Gutzlaff Signal Tower, built in 1907

(PengPai news, 2022; Can Pac Swire, 2011)

Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, significant improvements were made to Shanghai’s early warning system. The Shanghai Meteorological Bureau, founded in 1956, became responsible for weather forecasting. In 2003, the ‘Shanghai Disastrous Weather Early Warning Signal Issuance Regulations’ came into effect. This regulation defined the Meteorological Bureau’s duties in hazard emergency response and prevention, in line with the implementation measures of China’s Meteorological Law (China Meteorological Administration, 2010).

A transformative phase commenced in 2008 when, in response to President Hu Jintao’s call and backed by the China Meteorological Administration and the Shanghai Municipal Government, the Shanghai Meteorological Bureau began working on a Multi-Hazard Early Warning System (MHEWS). The system, constructed on the core principles of “government-led, inter-departmental coordination, and social participation,” zeroes in on key components of hazard prevention and mitigation. These include risk assessment, emergency plan formulation, monitoring and forecasting, warning dissemination, and inter-departmental coordination for meteorological and secondary derivative hazards. The MHEWS’s central goal is to offer timely and precise information to the public and government officials, promoting effective decision-making in hazards scenarios (Tang et.al, 2012).

Shanghai’s meteorological early warning system stands as a testament to the city’s long and evolving journey in hazards management. The launch of the MHEWS marks a significant leap forward in developing advanced, integrated surveillance and response systems that are custom-tailored to the myriad risks Shanghai faces.

Hong Kong and Shanghai’s warning systems have followed distinct evolutionary paths, guided by their unique contexts. In Hong Kong, the warning system is primarily spearheaded by the government, with the Hong Kong Observatory playing a key role. Various departments operate independently to ensure the system’s smooth operation. Contrastingly, Shanghai’s warning system is orchestrated around the Shanghai government, characterized by inter-departmental collaboration. These structural and governance differences bear significant implications, which we will delve deeper into in the subsequent sections of the blog.

3. Meteorological Warning Signals between Shanghai and Hong Kong

3.1 Shanghai

3.1.1 Structure of Shanghai ’s Warning System

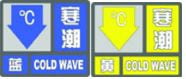

Shanghai’s meteorological warning system covers a wide range of hazard categories, including typhoons, heavy rain, snow, cold waves, strong winds, and more. It issues specific warnings for each category to ensure public safety (Shanghai Municipal People’s Government, 2019). The system has four levels of alerts (general, serious, severe, and extremely severe) color-coded as blue, yellow, orange, and red. The first two are advance warnings, while the last two signal ongoing severe weather and require immediate response from rescue departments. This system varies its warning levels based on weather type: two levels for phenomena such as cold waves and haze, three for events like heatwaves and road icing, and four for severe conditions like typhoons and gales (Shanghai Municipal People’s Government, 2019). This flexibility ensures precision in handling various meteorological threats.

Cold Wave signal

Haze signal

Heat Wave signal

Snowstorm Storm (Shanghai Meteorological Service, n.d.)

3.2 Hong Kong

3.2.1 Structure of Hong Kong’s Warning System

Unlike Shanghai, Hong Kong’s warning system comprises ten categories, with distinct symbols corresponding to different hazard types and severity levels such as tropical cyclone warnings, strong monsoon signals, rainstorm warnings, landslide warnings, and more. Notably, Hong Kong’s hazard warning system stands out for its simplicity and clarity (Hong Kong Observatory, 2021a).

For example, the rainstorm warning system operates on three levels: amber, red, and black. An amber signal indicates a potential rainstorm that may lead to traffic congestion. In contrast, a red signal denotes expected heavy rainfall that could disrupt traffic and advises citizens to remain indoors. The black signal warns of severe road blockages due to intense rainfall, with advice for people to seek safe shelter. Typhoon signals are broken down into levels one, three, eight, nine, and ten, while thunderstorm, landslide, and flood warnings are not graded. (Hong Kong Observatory, 2021b)

Figure 1: Weather Warnings and Signal Records

(Hong Kong Observatory, 2019)

Figure 2: Introduction to various warning icons

(Hong Kong Observatory, 2019)

3.2.1 Learning from Differences: Hong Kong’s System

In Hong Kong, warning information is effectively communicated and taught. From primary to secondary school levels, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government educates its citizens about crisis awareness. This ensures that every adult in Hong Kong is familiar with important alerts, such as the No. 8 typhoon signal and the black rainstorm warning (Lam et.al, 2017).

The warning information’s clarity and straightforward nature not only facilitate citizen understanding but also promote rapid dissemination, thereby reducing information distortion during the process. Moreover, the correlation between warning information and emergency measures in Hong Kong is highly effective. The city’s meteorological hazards emergency system offers detailed guidance on various warning signals and the corresponding actions emergency units should undertake. Consequently, each unit can promptly and appropriately respond to emergency situations based on the warning information.

For instance, precise regulations are in place under typhoon and heavy rain warning signals concerning school class suspension or exam rescheduling (Hong Kong Observatory, 2021b). This ensures a swift and efficient response to such situations, further underlining the system’s effectiveness.

4. Shanghai and Hong Kong: A Comparative Analysis of Warning Systems

The cities of Shanghai and Hong Kong, both notable for their bustling economies and high population densities, have distinct emergency warning systems. This comparison aims to highlight their differences and respective challenges, while also suggesting ways they might improve by learning from each other.

4.1 The Challenges Facing Shanghai’s Warning System

4.1.1. Lack of Clear and Consistent Grading:

Shanghai’s warning system has struggled with the absence of clear and consistent grading over an extended period. Various types of hazard warning information use similar color grading, leading to confusion among citizens. The presentation of crucial information is not straightforward, making it difficult for individuals to understand the severity of a warning and determine the appropriate response. For instance, typhoon warning signals in Shanghai are categorized into four levels, while rainstorm warning signals have three levels. However, the color grading used for these signals can be perplexing, hindering citizens’ ability to differentiate between the different levels.

4.1.2. Insufficient Education and Crisis Awareness:

Another notable issue in Shanghai’s warning system is the lack of education and cultivation of crisis awareness among the general population. Primary and secondary schools in Shanghai do not place enough emphasis on teaching students about hazards preparedness. Consequently, there is a deficiency in public awareness regarding the appropriate measures to take in response to warnings. This lack of awareness can lead to apathy towards warnings and a failure to recognize the urgency of taking necessary precautions, ultimately putting citizens at risk.

4.2 The Differences Between Shanghai’s and Hong Kong’s Warning Systems

Shanghai relies primarily on government notifications, disseminated by local meteorological bureaus through channels such as SMS, radio, TV, newspapers, electronic screens, telephone calls, fax, and dedicated websites. The system also incorporates self-organized community actions, encouraging individuals and communities to take proactive measures for emergencies. Shanghai’s grid-based management system ensures wide coverage, employing physical means like loudspeakers and community notifications. (Shanghai Meteorological Bureau,2010)

In contrast, Hong Kong’s warning system emphasizes information technology and public participation. The city has a well-developed public alert system, utilizing various communication channels, including mobile apps, social media platforms, and official websites. Major media outlets play a crucial role in rapidly disseminating typhoon warnings, while warning information is promptly released in public places and transportation departments. Hong Kong’s efficient system has contributed to maintaining a low casualty rate despite frequent typhoon occurrences.

4.2.1 The Impact on Shanghai:

Shanghai’s system lacks real-time responsiveness, leading to slower reaction times because it requires government intervention for information dissemination and plan execution. This slowness may result in delayed warnings and slower execution of emergency response plans.

4.2.2 The Impact on Hong Kong:

While Hong Kong’s system is fast, it can sometimes lead to misjudgments due to the independent release of warning information. For instance, a mistaken typhoon warning from the Hong Kong Observatory could disrupt work and school schedules, causing societal losses.

5. Recommendations for Improvements

In an era of increasing emergency events, both cities can enhance their warning systems by learning from each other and implementing technology better.

5.1 For Shanghai

Shanghai could streamline its warning release mechanism by integrating responsibilities across departments for more efficient warning releases. Improving IT capabilities within the warning system would also allow faster dissemination and execution of warnings. Furthermore, the categorization and grading of warning information should be simplified and made more specific, adopting different symbols for different types of hazards.

Additionally, Shanghai should look to expand the ways in which it disseminates warning information, incorporating new media such as social media, mobile apps, and emails. Lastly, Shanghai should also emphasize education on warning information to enhance public awareness and response.

5.2 For Hong Kong

Hong Kong could benefit from Shanghai’s strong community response capabilities, incorporating community needs into their warning system for better customization. Emphasizing the accuracy of warning information is also critical, reducing the potential for false alarms and enhancing public trust.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, while both cities have distinct warning systems in place, there’s room for improvement. By learning from each other’s practices and adapting to the challenges of an increasingly digital age, they can enhance public safety and reduce hazard impacts.

Reference

Bian, Y. J. (2020). Weather management: A modern history of Hong Kong and typhoons. PengPai News. Retrieved May 18, 2023, from: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_6318400

Can Pac Swire. (2011). The Bund Observatory / Gutzlaff Signal Tower. Flickr. Retrieved April 26, 2023, from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/18378305@N00/6080691633/in/photostream/

Chen, F., Lin, H., & Hu, X. (2014). Slope superficial displacement monitoring by small baseline SAR interferometry using data from L-band ALOS PALSAR and X-band TerraSAR: A case study of Hong Kong, China. Remote Sensing, 6(2), 1564–1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs6021564

China Meteorological Administration. (2012). Notice on defense against heavy rainfall and flood hazards. Retrieved April 19, 2023, from https://www.cma.gov.cn/2011xzt/2012zhuant/20120815/2012081516/201209/t20120911_184903.html

Civil Engineering and Development Department (CEDD). (2021). Hong Kong Geology: A 400-Million-Year Journey.. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from https://hkss.cedd.gov.hk/hkss/eng/education/gs/tc/hkg/chapter4.htm

CEDD. (2021). Hong Kong slope safety, major landslide accident. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from https://hkss.cedd.gov.hk/hkss/en/home/index.html

Government Headquarters Security Bureau Emergency Support Unit. (2007). Natural hazards contingency plan (including natural hazards caused by severe weather). Retrieved April 19, 2023, from http://www.sb.gov.hk/

Hong Kong Observatory. (2021a). History of the Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from https://www.hko.gov.hk/sc/abouthko/history.htm

Hong Kong Observatory. (2021b). Rainstorm warning system. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from https://www.hko.gov.hk/tc/wservice/warning/rainstor.htm

Hong Kong Observatory. (2023). Celebrating the 130th Anniversary of the Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved from https://www.hko.gov.hk/tc/130thAnniversary/130th_home.htm#

Hong Kong Observatory. (2019). Hong Kong Weather Warning and Signals. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from https://www.hko.gov.hk/tc/wxinfo/dailywx/wxwarntoday.htm

Huang, L., Chen, S., Pan, S., Li, P., & Ji, H. (2022). Impact of Storm Surge on the Yellow River Delta: Simulation and Analysis. WaDisasterter, 14(21), 3439. doi:10.3390/w14213439

Keegan, M. (2022). Climate Change and Natural s: The Past, Past and Future of Landslip Prevention in Hong Kong. BBC News. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/science-60782952

Lam, R. P. K., Leung, L. P., Balsari, S., Hsiao, K., Newnham, E., Patrick, K., Pham, P., & Leaning, J. (2017). Urban hazards preparedness of Hong Kong residents: A territory-wide survey. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 23, 62-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.04.008

Michigan State University. (n.d.). Hong Kong: Introduction. GlobalEdge. Retrieved July 29, 2023, from https://globaledge.msu.edu/countries/hong-kong

PengPai News. (2022). From the Bund signal tower to the information “second transmission”, Shanghai weather early warning has been done for more than 100 years. Retrieved May 18, 2023, from https://mbd.baidu.com/newspage/data/landingsuper

Shanghai Meteorological Bureau, CMA. (2010). Overview of Shanghai Multi-hazard Early Warning System and the Role of Meteorological Services. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from https://ane4bf-datap1.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/wmocms/s3fs-public/news/related_docs/Shanghai_MHEWS_CostaRica.pdf

Shanghai Meteorological Service. (n.d.). Early Warning Signals and Defense Guidelines. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from http://sh.cma.gov.cn/sh/news/yjjz/zhtqyj/

Shanghai Municipal People’s Government. (2019). Regulations on the Issuance and Dissemination of Early Warning Signals of Meteorological Disasters in Shanghai. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from http://service.shanghai.gov.hq/XingZhengWenDangKuJyh/XZGFDetails.aspx?docid=6970

State Council Information Office of PRC. (n.d.). Introduction of Shanghai. Retrieved April 13, 2023, from http://www.scio.gov.cn/ztk/dtzt/7/03/Document/485318/485318.htm

Tang, X., Feng, L., Zou, Y., & Mu, H. (2012). The Shanghai Multi-Hazard Early Warning System: Addressing the Challenge of Hazards Risk Reduction in an Urban Megalopolis. In M. Golnar (Ed.), Institutional Partnerships in Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems (pp. 85-97). Springer.

Wang, B., Loo, B. P. Y., Zhen, F., & Xi, G. (2020). Urban response from the lens of social media data: Responses to urban flooding in Nanjing, China. Cities, 106, 102884. doi:10.1016/j.parl.2020.102884

Xu, D., Ouyang, Z., Wu, T., & Han, B. (2020). Dynamic trends of urban flooding mitigation services in Shenzhen, China. Sustainability, 12(11), 4799. doi:10.3390/Su12114799

Zhao, Q., Pan, J., Devlin, A. T., Tang, M., Yao, C., Zamparelli, V., Falabella, F., & Pepe, A. (2022). On the Exploitation of Remote Sensing Technologies for the node of coastal and River Delta regions. Remote Sense Signal, 14(10), 2384. doi:10.3390/rs14102384

The Function and Structure of an Early Warning and Action Initiative

By Amanda Gallant, on 28 February 2023

By: Michael H.Glantz

February 27, 2023

CCB, Boulder

INSTAAR, University of Colorado

The function (what gets done) of an early warning system, regardless of what acronym is used to describe it, is to provide timely warnings individuals, groups, communities, political jurisdictions from county to country levels about potential climate, water or weather related (hydromet) threats to society. It could range from quick onset hydromet hazards to slow onset, creping ones. It is used to minimize if not avoid altogether the adverse consequences of a climate, water, or weather anomaly, to save lives, personal possessions, property, and all kinds of infrastructure. In theory at least those are desired and sought-after objectives. In practice, however, it has proven time and again to be a difficult task to achieve, given may socio-economic challenges (obstacles, constraints, or pitfalls encountered by those responsible for developing preparedness, readiness and response policies and enforcing them. Disaster after disaster — even the same kinds in the same place — societies try to invent ways to do better the next time, to cope more effectively and efficiently with such hydromet threats. Societies do not give up. Part of the problem in timely and effective preparation and/or responses has to do with the structure of the warning system and the bureaucratic process that are or should be integral parts of it.

Structure (how what gets done [function] gets done) is a different matter. It makes a difference what the name of the initiative, as it indicates the type of organization that could carry out the purpose of the initiative. There are several types or organizational structures, each with its pros and cons (Williams no date). There can also be a hybrid structures putting together the best positive features of each of the structures, while addressing the cons.

Perhaps the most common one is hierarchical, a pyramid like, with executives and the top, middle management and staff level employees at the base. According to Williams (n.d.), this structure “better defines levels of authority and responsibility…. However, it “can slow down innovation or important changes due to increase bureaucracy” and can make staff at the base of the pyramid “feel like they have less ownership and can’t express their ideas.”

There can also be a divisional top-down organizational structure, where “each division” operates autonomously within the overarching structure and has control over its own resources and operate separately from other divisions in the larger organization.

What will the structure designed by the WMO, the UNDRR and other organizations as advisers, use to enhance the EWEA or the EW4A? Perhaps the structure would be both descriptive acronyms by thinking more broadly of ways to combine the strengths and avoid the weaknesses by making explicit their overlapping but different set of goals: EWEA + EW4A = EWEA4A.

Doing so would enable the EW4A to be the overarching umbrella for lots of things: those activities with EA in their names do not have to change anything and continue; AA (Anticipatory Action) is also at play and, most importantly, regional EWEA centers can be developed where the EWEA4A can be tailored to address regional hydromet-related hazards and needs.

Everybody wins.

Refugees and the Turkey-Syria (Kahramanmaras) Earthquake

By Amanda Gallant, on 15 February 2023

By Mhari Gordon

Nine days after the Kahramanmaras Earthquake on the 6th of February, the collapse of buildings and harsh winter weather conditions have raised the recorded death toll between Turkey and Syria to over 41,000 (Rasheed and Stepansky, 2023).

There are currently 5.5 million foreigners living in Turkey, including 3.7 million Syrian refugees, 320,000 people under international protection, mainly Afghans (UNHCR, 2022; Uras, 2022), 46,000 Ukrainians (Ukrinform, 2022) and 153,000 Russians (The Moscow Times, 2023) – since February 2022 fleeing Russia’s war on Ukraine – as well as other migrants.

Millions of refugees live in areas most affected by the earthquake (France 24, 2023). In Syria, 57,000 Palestinian refugees live in 3 refugee camps in the quake-affected north (France 24, 2023). In Turkey, approximately 2 million Syrian refugees are living in south-eastern Turkey (ACAPS, 2023). Over 90% of Syrian refugees live among local Turkish populations, in buildings which are highly vulnerable to earthquake shaking (IOM, 2017).

There has been widespread concern about the quality of buildings and infrastructure to withstand earthquakes. Despite the upgrade of building codes and stricter safety standards in the past 55 years, there has been a lack of regular and reliable inspection to ensure its enforcement and retrofitting of existing structures (Alexander, 2023; Lewis, 2003). These failures have led to mass fatalities and injuries, as well as homes and belongings lost due to collapsed and damaged buildings. The Kahramanmaras Earthquake has again highlighted the need for effective disaster prevention and preparedness.

Whilst Turkey is one of the only countries which includes migrants in their Disaster Risk Reduction policies, as it stands, there is currently limited information about the specific needs of migrants and refugees following the earthquake (ACAPS, 2023).

A UNHCR representative shared that they predict the refugee camps in south-eastern Turkey, which are already inhabited by 47,000 refugees, will be where earthquake-affected victims will seek refuge and medical assistance due to the already existing humanitarian systems and aid corridors (France 24, 2023). However, many of the key access roads are unsafe or damaged, also affected by the snow and rain of the winter storm, impacting the movement of people and resources including aid delivery (ACAPS, 2023; Al Jazeera, 2023). This has also significantly delayed search and rescue teams and aid getting to affected areas. For example, the south-eastern Turkish province of Hatay has only received external help 5 days after the initial earthquake with its airports reopening (Rasheed and Stepansky, 2023). In Syria, the response has been slower and delivering aid has been further complicated by restricted access (The Guardian, 2023). As seen in other earthquake-triggered disasters, citizens are the first responders pulling people out of the rubble and gathering resources. In Turkey, many Syrian refugees are participating alongside locals in the search and rescue of people as volunteers (France 24, 2023).

Many people who have sought refuge in Turkey and Syria may be subject to moving again, however, the accessibility and choice of relocation could be severely restricted depending on the availability of resources such as transport and money. This can place them in further precarious situations and increase the challenges of resettlement. Research has shown that in cases of other earthquake-triggered disasters, such as in Japan 2011 and New Zealand 2010-2011 (see studies by Uekusa and Matthewman (2017) and Ikeda and Garces-Ozanne (2019)), refugees and migrants were heavily involved in the immediate aftermath and recovery stages following the disasters, but there was confusion amongst the non-citizens on which resources they could access. Critical information was disseminated in languages or formats that were not suitable or inclusive of refugees and migrants. In these cases, local NGOs stepped in to circulate around migrant communities to relay and translate information, however, this required strong social and support networks. Appropriate warnings and information dissemination are key in helping people prepare for and recover from the impacts of hazards.

The following weeks and months will be significant for the recovery of people living in Turkey and Syria following this disaster, especially regarding the support needed for refugees and other migrant populations.

Reference List

ACAPS (2023) Briefing note: Earthquakes in south-eastern Türkiye and north-western Syria, ACAPS. Available at: https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/products/files/20230207_acaps_briefing_note_turkiye_and_syria_earthquake_0.pdf (Accessed: February 9, 2023).

Al Jazeera (2023) Severe weather hampers earthquake rescuers in Turkey and Syria, Earthquakes News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/2/6/severe-weather-hampers-earthquake-rescue-in-turkey-and-syria (Accessed: February 9, 2023).

Alexander, D. (2023) Reflections on the Turkish-Syrian Earthquakes of 6th February 2023: Building Collapse and its Consequences, UCL IRDR Blog. Available at: https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/irdr/2023/02/09/reflections-on-the-turkish-syrian-earthquakes/ (Accessed: February 9, 2023).

France 24 (2023) Millions of vulnerable refugees in Turkey-syria quake zone, France 24. France 24. Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230207-millions-of-vulnerable-refugees-in-turkey-syria-quake-zone (Accessed: February 9, 2023).

Ikeda, MM. and Garces-Ozanne, A. (2019) ‘Importance of self-help and mutual assistance among migrants during natural disasters’, WIT Transactions on the Built Environment, 190, pp. 65–77.

Lewis, J., (2003). Housing construction in earthquake-prone places: Perspectives, priorities and projections for development. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 18(2), pp.35-44.

Rasheed, Z. and Stepansky, J. (2023) Turkey-syria quake rescue phase ‘coming to a close’: Un, Turkey-Syria Earthquake News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/liveblog/2023/2/13/turkey-syria-earthquake-live-news-us-urges-un-vote-on-aid-access (Accessed: February 15, 2023).

The Guardian (2023) Syria earthquake aid held up as millions suffer in freezing conditions, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/feb/13/syria-earthquake-aid-held-up-as-millions-suffer-in-freezing-conditions (Accessed: February 13, 2023).

The Moscow Times (2023) Turkey stops granting residence permits to new Russian arrivals – report, The Moscow Times. The Moscow Times. Available at: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/01/23/turkey-stops-granting-residence-permits-to-new-russian-arrivals-report-a80018 (Accessed: February 13, 2023).

Uekusa, S. and Matthewman, S. (2017) ‘Vulnerable and resilient? Immigrants and refugees in the 2010–2011 Canterbury and Tohoku disasters’, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22, pp. 355–361.

Ukrinform (2022) Since war-start, 279,000 Ukrainian citizens arrive in Turkey, 46,000 remain, Ukrinform. Укринформ. Available at: https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-society/3538094-since-warstart-279000-ukrainian-citizens-arrive-in-turkey-46000-remain.html (Accessed: February 13, 2023).

Uras, U. (2022) Rising anti-refugee sentiment leads to debate in Turkey, News | Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/7/27/rising-anti-refugee-sentiment-leads-debate-turkey (Accessed: February 9, 2023).

A Note of Warning Blog 3: Warnings for Displaced People

By Amanda Gallant, on 13 October 2022

By Mhari Gordon

The occurrence of a natural hazard, such as a cyclone or landslide, near or in an inhabited area has the potential to disturb livelihood, infrastructure, societal practices and functioning, and ecosystems (Ahmed et al., 2019; Hyvärinen and Vos, 2015). Although natural hazards may spatially reach all members of a population within an area, such impacts are neither felt nor distributed evenly throughout society. Depending on the existing resources and techniques of the affected society to respond to a natural hazard occurrence, the impacts have the potential to be disastrous (Kelman, 2022). By definition, a disaster is when a population experiences disruptions, damages, and losses that occur as a consequence of the impact of a hazard, which is usually considered to have ‘great’ or ‘catastrophic’ effects (Wisner, Gaillard, and Kelman, 2012). Early warning and action have been shown to be one of the most effective ways to reduce impact, loss, and damage from natural hazards and potential disasters (WMO, 2022).

Individuals and communities who are displaced by the impact of conflict situations, such as internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees, are often found to be marginalised within their host communities (Pollock et al., 2019). This marginalisation will transpire in different forms depending on the context such as physical separation, in the likes of refugee camps, or less obvious forms, in the likes of (informal) urban settlements, but also bound by the socio-political-economic policies created by the host government for these individuals (Van Den Hoek, Wrathall, and Friedrich, 2021). Marginalised populations have been presumed to be highly vulnerable to disasters (Lejano, Rahman, and Kabir, 2020). Here, vulnerability is understood as the physical, social, economic, political, and environmental characteristics of a community which may be impacted by a hazard and influence their ability to cope and respond (Ahmed et al., 2021). However, refugees’ vulnerabilities are likely to differ from marginalised ‘local’ populations (Zaman et al., 2020); as the host government’s policies for access to knowledge, communication, and education, as well as resources and facilities (i.e., cyclone shelters), will largely influence the displaced population’s vulnerability to hazard risks. To date, there has been relatively little disaster risk reduction (DRR) research which considers displaced populations, including internally displaced persons, refugees, and other migrants (Zaman et al., 2020).

Risk Communication and Warnings

Literature from disasters in urban and rural contexts, as well as climate change studies, show that risk perception and disaster experience affect an individual’s interpretation of risk information and action on mitigation hazard risk (Acosta et al., 2016; Bempah and Øyhus, 2017; Wulandari, Sagala, and Coffey, 2016). Thereby, unpacking the narratives of a population’s perception, experience, and action of risks is important to be able to design appropriate mitigation strategies and communication plans. Failures resulting in catastrophic loss and damage are unfortunately present, because of poor planning and response to hazards, such as the 2008 Hurricane Katerina in New Orleans. This has become a staple example of contradictory and unclear communication and information dissemination as well as deep socio-economic inequalities, which led to unequally distributed, and likely avoidable, loss and damage within New Orleans communities (Hanson-Easey et al., 2018). Yet, there are examples of successful mitigation of disastrous impacts from natural hazard occurrences. For example, cyclone-related mortality has declined from hundreds of thousands of deaths in the early 1970s to a few thousand in the late 2000s in Bangladesh with the implementation of early warning systems, awareness campaigns, cyclone shelters, and nature-based solutions have been implemented (Haque et al., 2012). The effectiveness of appropriate communication and warnings has recently received greater societal attention, with the announcement on the 23rd of March 2022 from the United Nations and World Meteorological Organization:

“Within the next five years, everyone on Earth should be protected by early warning systems against increasingly extreme weather and climate change, according to an ambitious new United Nations target… We must boost the power of prediction for everyone and build their capacity to act. On this World Meteorological Day, let us recognize the value of early warnings and early action as critical tools to reduce disaster risk and support climate adaptation.” (WMO, 2022).

However, more research is needed into how warnings and communication plans can be made accessible to all members of society. For plans to be effective, the people who are at risk of the impacts of a hazard or a disaster need to be the focal point.

Local-focused Warnings

Since the 2010s, there has been a notable trend in DRR, climate change, and humanitarian discourses that there is strong advocacy for the focus on the ‘local level’ for matters of disaster planning and response (Hyvärinen and Vos, 2015). This push for a ‘specific context-based’ focus is also reflected in the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction’s (UNDRR) Sendai Framework, and is included in one of the Priorities of Action:

“To ensure the use of traditional, indigenous and local knowledge and practices, as appropriate, to complement scientific knowledge in disaster risk assessment and the development and implementation of policies, strategies, plans and programmes” (UNDRR, 2015: 14).

The terms traditional, indigenous, and local are frequently cited in documentation (policy, research, academia, etc), however, there is a lack of clarity on the defining characteristics of these terms. Yet, findings often indicate that the likes of ‘risk perceptions’, ‘disaster knowledge’ or ‘mitigation action’ differ depending on the label (traditional, indigenous, local, migrate, etc) that is allocated to a specific group of people. For example, Ahmed’s (2021) research on landslide vulnerability in Bangladesh findings indicated that the urbanised hillside communities (local) and the Rohingya refugees (refugee) residing in and around the Kutupalong camps had higher vulnerabilities to landslide risk than the tribal communities (indigenous). The difference in vulnerabilities was attributed to tribal communities’ “unique history, traditional knowledge, cultural heritage and lifestyle” (Ahmed, 2021: 1707). Interestingly, the local and refugee communities were both found to be more vulnerable to landslide risk, but these were in different ways. Given that there are close to one million Rohingya refugees living predominantly in Cox’s Bazar District (Ahmed, 2021), understanding their specific vulnerabilities and best forms of warnings against natural hazards requires further research.

Moving Forwards

Further research should focus on how displaced communities are affected, within the context of the host community’s vulnerability, by the societal impacts of natural hazard occurrences. Also, how their risk perceptions, knowledge, and experiences, as well as vulnerabilities, may differ from the local communities. This will enable displaced populations to be accounted for and included in the appropriate design of effective warnings against hazards, thereby pushing the agenda forwards to meet the Sendai Framework Target G, and the UN and WMO objective that everyone has access to early warning and action within the next five years.

“Bangladesh: a year of bringing relief to Rohingya refugees” by EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Reference List

Acosta, L.A., Eugenio, E.A., Macandog, P.B.M., Magcale-Macandog, D.B., Lin, E.K.H., Abucay, E.R., Cura, A.L. and Primavera, M.G., (2016). Loss and damage from typhoon induced floods and landslides in the Philippines: community perceptions on climate impacts and adaptation options. International Journal of Global Warming, 9(1), pp.33-65.

Ahmed, B., (2021). The root causes of landslide vulnerability in Bangladesh. Landslides, 18(5), pp.1707-1720.

Ahmed, B., Sammonds, P., Saville, N.M., Le Masson, V., Suri, K., Bhat, G.M., Hakhoo, N., Jolden, T., Hussain, G., Wangmo, K. and Thusu, B., (2019). Indigenous mountain people’s risk perception to environmental hazards in border conflict areas. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 35, p.101063.

Bempah, S. A., and Øyhus, A. O. (2017). The role of social perception in disaster risk reduction: beliefs, perception, and attitudes regarding flood disasters in communities along the Volta River, Ghana. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 23, pp. 104-108.

Hanson-Easey, S., Every, D., Hansen, A. and Bi, P., (2018). Risk communication for new and emerging communities: the contingent role of social capital. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 28, pp.620-628.

Haque, U., Hashizume, M., Kolivras, K.N., Overgaard, H.J., Das, B. and Yamamoto, T., (2012). Reduced death rates from cyclones in Bangladesh: what more needs to be done?. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90, pp.150-156.

Kelman, I. (2022) Pakistan’s floods are a disaster – but they didn’t have to be. [online]. 20 September 2022. The Conversation. Available from: https://theconversation.com/pakistans-floods-are-a-disaster-but-they-didnt-have-to-be-190027 [Accessed: 12 October 2022].

Lejano, R.P., Rahman, M.S. and Kabir, L., (2020). Risk Communication for empowerment: Interventions in a Rohingya refugee settlement. Risk Analysis, 40(11), pp.2360-2372.

Pollock, W., Wartman, J., Abou-Jaoude, G. and Grant, A., (2019). Risk at the margins: a natural hazards perspective on the Syrian refugee crisis in Lebanon. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 36, p.101037.

UNDRR, (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030. [pdf] United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Available at: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf [Accessed 16 May 2022].

Van Den Hoek, J., Wrathall, D., and Friedrich, H., (2021) Population-Environment Research Network (PERN) Cyberseminars A Primer on Refugee-Environment Relationships.

Wisner, B., Gaillard, J.C. and Kelman, I., (2012). Framing disaster: Theories and stories seeking to understand hazards, vulnerability and risk. In The Routledge handbook of hazards and disaster risk reduction (pp. 18-33). Routledge.

WMO, (2022). Early Warning systems must protect everyone within five years. [online] World Meteorological Organization. Available at: <https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/%E2%80%8Bearly-warning-systems-must-protect-everyone-within-five-years> [Accessed 20 September 2022].

Wulandari, Y., Sagala, S. and Coffey, M., (2016). The Impact of Major Geological Hazards to Resilience Community in Indonesia. Resilience Development Initiative.

Zaman, S., Sammonds, P., Ahmed, B. and Rahman, T., (2020). Disaster risk reduction in conflict contexts: Lessons learned from the lived experiences of Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 50, p.101694.

A Note of Warning Blog 2: The Nirvana of Multi-Hazard Warnings

By Amanda Gallant, on 13 October 2022

By Carina Fearnley

On International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction (IDDRR) I write this blog article with Mt Vesuvius volcano in the corner of my vision. It reminds me of the immense challenges faced by the multiple hazards that volcanoes produce, often for populations that are not fully aware of the diversity, strength, and rapidity of these hazards, whether erupting or not. For 2022 the focus of IDDRR is on Target G of the Sendai Framework to: “Substantially increase the availability of and access to multi-hazard early warning systems and disaster risk information and assessments to people by 2030.” Every year we witness several complex multi-hazard situations, whether they coincide, are caused by one another, or generate cascading hazards. The interaction between them is simply a disaster manager’s nightmare.

During the COVID-19 pandemic we saw the challenges of having to evacuate people from flooding, or earthquakes to evacuation sites, where isolating from COVID-19 was difficult to achieve. These types of difficult DRR actions place pressure on managing hazards, some of which may be predictable, as others may emerge unexpectedly. Working across different hazards presents significant challenges to agencies, who have to make sense of what to do when there is new data coming in, often in isolation to other hazards, and conflicting action typically with a lot of uncertainty. This whole process is not made any easier by the added complexity of anthropogenic global warming, a range of relatively new human-made threats from the technologies we have developed, and the interactions and exploitations we have had on the environment.

Therefore it is appropriate on IDDRR to ask how is it possible to set up a multi-hazard warning system? The World Meteorological Organization produced a Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems: A Checklist in 2018. This phenomenal document attempts to “bring together the main components and actions to which national governments, community organizations and partners within and across all sectors can refer when developing or evaluating early warning systems”. It is, however, not a comprehensive design manual and provides limited insights into how to actually DO multi-hazard early warning systems (MHEWS). The report does however, help highlight the multiple facets involved that work beyond a single hazards warning system, as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic of a multi-hazard early warning system (taken from Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems: A Checklist, WMO, p.6)

The Third Multi-Hazard Early Warning Conference (MHEWC-III) at the 7th Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction 2022 was held in Bali and I went with full anticipation to learn how to do MHEWS. Instead I established:

- No-one really knows how to do multi-hazard warnings

- People are talking about the last mile but far less about the first mile process

- Warnings are still generally spoken of as technocratic tools

- There is a huge interest in warnings and how to make them efficient, and a clear need for some academic expertise / input / verification

Part of the issue is that there is not enough analysis of multi-hazard events to establish how successful or not the management of the situation was, in part because it is hard to establish whether if different choices had been made, the impact would have been lesser or greater. Simulations and drills can provide significant insights.

There are however some brilliant examples of MHEWS that provide some strong indicators on how best to do MHEWS, the first can be drawn from volcanic hazards, and the second from women-led groups.

The Ultimate Multi-Hazard

Volcanoes often generate multiple hazards that occur at the same time, affecting different locations. For example a pyroclastic flow can affect those within close proximity of the volcano, but volcanic ash generated can affect populations thousands of kilometres downwind, creating transport and logistical problems. These are just the primary hazards. Secondary hazards can be generated such as landslides, tsunami, famine, climate change and many more. Each of these hazards requires different actions and considerations, yet are simply part of the challenge of managing a volcanic eruption. Different experts within the disciplines Volcanology, Meteorology, Seismology, Tsunami, have to work together to monitor volcano generated hazards. Often volcanoes occur on or near national borders and have to work across different jurisdictions on local, regional, and national levels. Volcano observatories have been managing these multiple and complex hazards since 1841 when the Vesuvius Observatory was founded, and have developed and implemented numerous warning systems for volcanic hazards (albeit still rather separate) that work together to reduce disaster risk reduction from volcanic hazards working across a wide range of hazard organisations, and also government, public, NGO, and private entities.

An excellent example includes the Eyjafjallajökull volcano that erupted in in Iceland during 2010 (see fig. 2). The Icelandic Meteorological Office worked with Icelandic and global scientists along with the Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management to manage the local hazards of lava flows, volcanic ash, and jökulhlaups, alongside the secondary impact on agriculture and tourism. In addition the warnings involved liaising with the London Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre, World Meteorological Organization, and International Civil Aviation Organization to manage the ash risk to aircraft all over Europe. Such a complex and multi-hazard warning system built upon well established relationships, that had been tested via simulation scenarios, and took advantage of local and national networks to provide effective warnings.

Figure 2. Eyjafjallajökull erupted in March-May 2010, going from an effusive lava flow, to an explosive eruption producing extensive ash causing the longest closure of airspace in Europe since the second World War. Source: S. Stefnission www.stefnisson.com

Volcanoes provide valuable insights into how to operationally work across multiple agencies to collaborate when a situation produces a wide range primary hazards, and secondary ones too. Some key lessons that can be identified from the volcano community on how to operationalise MHEW:

- Translation and multi-way communication are required to ensure that all involved in designing and assigning warnings understand what information is credible and relevant for each hazard – this involves working across the various actors providing hazard information, and overcoming lots of silos.

- Warning systems are complex and nonlinear. A consideration of different understandings of uncertainty and risk is required for decision-making processes in assigning warnings and actions across the hazards, including institutional and cultural dynamics of the organisations involved.

- Whilst standardisation of warning systems is vital to convey information to a wide range of stakeholders, standardisation is difficult to implement due to the diversity and uncertain nature of hazards at different temporal and spatial scales.

These recommendations assist operationally to bring together MHEWS, but how can these work with the most vulnerable, the people affected?

Insights from Women in Fiji on how to develop inclusive and accessible multi-hazard early-warning systems

Across the Asia-Pacific region there have been a number of incredibly successful MHEWS that have not only captured the multi-hazard complexities, but also been inclusive and accessible. Four key women-led and disability-inclusive MHEWS have been established in the Pacific Region: Vanuatu’s Women Wetem Weta, Papua New Guinea’s Meri Got Infomesen, Fiji Disabled People’s Federation Emergency Operations Centre, and Fiji Women’s Weather Watch. These are all discussed in the Inclusive and accessible multi-hazard early-warning systems report published by United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, Shifting the Power Coalition, ActionAid – Australia, and Women’s International Network for Disaster Risk Reduction.

Looking specifically at the Fiji Women’s Weather Watch, the initiative was driven by two key events, flooding in North Fiji in 2004, and the aftermath of Cyclone Mick in 2009, when it became clear that local women had been excluded from designing, planning and implementing disaster reduction efforts, and excluded from the relief efforts. Fijian women led this initiative to monitor and warn about weather through exchanging with and interpreting messages from the Fiji Meteorological Service, receiving training to develop their communication and engagement skills to ensure useful translation of the technical information into messages in local languages to which people can respond (see fig. 3).

Figure 3. At the Fiji Women’s Weather Watch, 12 women from the region were trained radio broadcasting skills to effectively communicate weather watch news at community level. Picture: LICE MOVONO

Core to the success of these MHEWS is highlighted in the report as: strong connections with communities, and regular and inclusive engagement with communities to facilitate trust and positive relationships between programme implementers and community members. In essence the more inclusive a MHEWS is, the more likely initiatives will be sustainable and reflect the needs and priorities of all community members, for a range of hazards. Once the network is established, whether the warning is for flooding, COVID-19, volcanic eruptions, it works to provide multi-directional communication to empower those that make the key decisions on safety, and facilitate open dialogue, questions, clarity, concerns, advice etc. By building on existing networks MHEWS do not add to the everyday, but become part of it Ultimately these MHEWS examples demonstrate that to be effective, inclusive and accessible, MHEWS should integrate local and traditional knowledge and draw on the wealth of local disaster risk knowledge from all community members to enhance the overall effectiveness of MHEWS. They remain exemplary for the rest of the global community.

Working globally for MHEWS for all

Following the announcement by António Guterres UN Secretary General on 23rd March 2022, for countries to ensure that citizens worldwide are protected by early warning systems against extreme weather and climate change, the focus on the role of warnings as part of early action has been heightened globally, as everyone asks, how can we do MHEWS better? The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is spearheading this new action and will lead the effort and present an action plan in November at this year’s UN climate conference (COP 27) in Egypt. Numerous agencies are now keen to contribute to the WMO led initiative, as everyone is working to achieve the target. More than ever we need to bring together case studies and lessons learnt, positive or negative, to help build better MHEWS for all.

To celebrate the focus on warnings for this IDDRR, the UCL Warning Research Centre launches our Warnings Briefing Notes series, supported by the Global Disaster Preparedness Center and The Anticipation Hub. These two-page documents are designed to provide a quick and accessible insight into various aspects of warnings, providing the state of the art of research, core needs, and high-level guidance and recommendations. These notes also provide a core case study, and graphic to help illustrate the key issues, alongside recommended sources for additional information. We are launching the first three Warnings Briefing Notes today, and a series of notes will be launched in the run up to COP27 to provide further information about the various aspects of warnings.

A Note of Warning Blog 1: An Introduction

By Amanda Gallant, on 13 October 2022

By Carina Fearnley, Ilan Kelman & Claudia Fernandez de Cordoba Farini

We are happy to inaugurate the UCL Warning Research Centre Blog Page on today’s International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction. Per the United Nations, this year’s call to action is on Target G of the Sendai Framework that is to “substantially increase the availability of and access to multi-hazard early warning systems and disaster risk information and assessments to people by 2030.”

At the core of the UCL Warning Research Centre is the goal to improve the effectiveness, access, and integration of warning systems across different communities, scales, disciplines and hazards. To achieve that, the UCL Warning Research Centre has pledged to become a centre for academic excellence and a hub for collaboration both within UCL, as well as with universities globally, businesses, government, non-governmental, and intergovernmental organisations.

This blog page will help to facilitate engagement with the global community of experts studying, researching, working with, or using warning and alert systems. It will make information and insights publicly accessible in the form of either lived experiences, short research analyses, policy guidance, applications and collaborative work.

You can already find a range of blogs and podcasts readily accessible on for example:

- Why some warnings are not being heard or acted on

- The first mile of warning systems: who’s sharing what with whom?

- Designing infectious diseases warnings that work

- Pakistan’s floods are a disaster – but they didn’t have to be

- Lessons From Volcano Warnings In Predicting The Next Pandemic

And we hope to share many more over the coming months and years.

Welcome to the Warning Research Centre Blog!

By Amanda Gallant, on 5 October 2022

Welcome to the Warning Research Centre blog!

We’ll be sharing insights and resources about our exciting work at UCL and beyond, as well as collaborations with the warning community in the UK and globally.

Close

Close