Dr Caroline Dalton has a PhD in Cell Biology from UCL. In this interview, Caroline tells us about her decision to leave academia, and her current role as a Research Funding Manager at Cancer Research UK.

How did you move from academia to your current role?

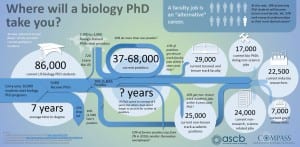

I had a bit of an ongoing battle inside myself during my PhD. I really enjoyed being in the lab, and the whole concept of science; finding a question that I’d like to answer, and working out the best way to answer it. But as I got further through my PhD, I became aware of the realities of a life in academia – the poor work/life balance, the lack of stability, and the scarcity of permanent higher-level positions – and I realised that a research career probably wasn’t for me.

So alongside my PhD and post-doc, I tried to get a sense of what else was out there. I knew I wanted to get out of the lab, but I also wanted to stay in science somehow, and by doing internet research, and going along to careers talks and events, I found out I had lots of options. I also tried a few things out to gage what I’d like most; I did a bit of public engagement in the form of ‘I’m a scientist, get me out of here’, I volunteered at a science festival, I went to a science policy workshop at Westminster, and attended various policy debates.

It turned out that I enjoyed all of these experiences, so when it came to job-hunting, my applications were actually fairly broad. But trying new things helped me to better understand the job roles that I was going for, and it also looked great on my CV and in interviews, as it demonstrated that I’d investigated the world outside of the lab. My first job coming out of research was working in policy for Breakthrough Breast Cancer for just under a year and a half. I liked the policy aspects of that role, however, I found I wasn’t using my science background enough, as the role was more health-service-focused. That’s why I moved into my current role as Research Funding Manager at CRUK – to get back in touch with the science.

Is having a PhD necessary for working in your current role?

A PhD isn’t essential for becoming a CRUK Research Funding Manager, but as it helps to have an understanding of the research environment, many of my colleagues do have PhDs. The role involves reading, understanding, summarising, and critically appraising research proposals, so I’m using a lot of the scientific skills I picked up in research. I also communicate with many different people and coordinate a variety of activities, so I’m using the project-management, organisation, and communication skills I developed in research too.

What does a normal working day look like for you?

I work on CRUK’s Clinical Trials Awards Advisory Committee, so the bulk of my role involves processing funding applications, and organising the scientific committee meeting that determines how funding will be awarded. Exactly what I’m doing each day depends very much on where we are in the review cycle, but it will usually entail things like answering queries from researchers hoping to apply for funding, reading research applications and writing an office summary of each one, sourcing appropriate peer reviewers for each application, checking the peer-reviewers’ responses, getting reviews back to applicants so they can respond, processing those responses, then preparing for and coordinating the actual committee meeting, and writing to applicants with committee feedback. There’s a fair bit of admin involved, but we’re assisted by Grants Officers who deal with a lot of the more basic administrative elements of the process.

What are the best things about working in your role?

It’s exciting to see the latest developments in science before they’ve even happened/been funded, and to be privy to the high-level discussions that happen at the committee meetings, and the expert reviewer comments on cutting-edge science. That’s the main thing that attracted me to the role. I also enjoy using my writing skills to craft responses to applicants reflecting the committee’s feedback on their proposals.

This is probably more team-, or CRUK-specific, than a part of the role per se, but the working environment is great. Everyone’s really helpful and open to suggestions for new ways of doing things, whatever level they or you are at. And there’s a much better work/life balance in this role than I would have had in academia, and it’s a permanent role, which obviously adds an element of stability that was lacking in research.

What are the biggest challenges you face?

In research I was extremely independent. It’s actually quite nice being part of a team now that’s trying to achieve something, as opposed to a single person trying to achieve something. But it does mean that there are a lot more people and processes involved in decision-making. In research, you’re pretty much free to try new things, as long as money and your supervisor allows. But outside of academia there are usually far more levels of bureaucracy involved.

What’s the progression like/where do you see yourself going from here?

I don’t know if there’s necessarily a ‘typical’ career path in research funding – there are lots of options. You could progress upwards in the team by applying for vacancies when they come up, like my managers have done. Or some people go on to do similar jobs in other charities and research funders, while others move to universities to manage grant applications from that side. Some people move on to more research-policy-focused roles, and potentially that might be a future direction that I might like to take. It also seems to be fairly common for people to move around and try new things within CRUK – I think that’s positively encouraged here.

What top tips would you pass on to current researchers interested in this type of work?

If you think you might want to work in research funding, I’d advise speaking to people in the area, and making sure you know what the funding landscape looks like. It can also help if you’ve been involved in the peer-review process before, so volunteer to review papers for journals, or ask your supervisor if you can help with reviews they’re doing.

And I’d definitely recommend using the UCL careers service! They made me far less terrified of the task ahead, helping me to identify and sell the skills that employers care about, which really boosted my confidence.

People leave academia for all sorts of reasons. For some it’s an active choice: maybe they want more job security or a better work-life balance, or maybe they’re just not as fond of research as they had once anticipated. For others the decision may be taken out of their hands, as they move from post-doc to post-doc, finding it increasingly difficult to secure the next role or chunk of funding. Dr Shelley Sandiford, ex-researcher and founder of science communication business Sciconic, has written a Next Scientist article to encourage those in the latter group to make the move out of academia before “wasting years in postdocs”.

People leave academia for all sorts of reasons. For some it’s an active choice: maybe they want more job security or a better work-life balance, or maybe they’re just not as fond of research as they had once anticipated. For others the decision may be taken out of their hands, as they move from post-doc to post-doc, finding it increasingly difficult to secure the next role or chunk of funding. Dr Shelley Sandiford, ex-researcher and founder of science communication business Sciconic, has written a Next Scientist article to encourage those in the latter group to make the move out of academia before “wasting years in postdocs”. Close

Close