Making a career of careers

By uczjsdd, on 3 August 2021

Dr Alice Moon has a PhD in Biochemistry, and now works here at UCL Careers as a careers consultant for the Engineering faculty, working with departments to offer careers support to their students. Alice kindly told how she got here, and shared her top tips for researchers considering leaving academia.

How did you move from your PhD to this role?

I did my PhD for the classic terrible reason that I didn’t know what else to do. I performed well in my degree, and I had a tutor who said I should do a PhD, so I did. I hadn’t done much of the careers thinking I now recognise as so important. Despite this, I quite enjoyed many aspects of research, and I found myself wanting to be an academic. However, after my PhD I did a couple of post-docs which generated pretty unexciting results, so it would have been a bit of a battle to stay in academia. And at the same time I felt like my values were changing. I looked around at work and didn’t see any role models I wanted to be. It still seemed really difficult in academia even at the supervisory level, with constant applications for funding, a need to move around to get jobs, and being impacted by larger institutional decisions.

So I left my post-doc, but again I did it without doing much careers thinking. I simply knew I no longer wanted to be an academic, and had a feeling there must be something better suited to me out there. I didn’t know what my options were with a PhD, and I’d always used and been interested in science, so I tried to get into intellectual property, but I wasn’t hearing back on my applications. My partner at the time was a scientist and wanting to leave, and he was applying to accountancy grad schemes. I felt like that wasn’t for me, but then he told me about the National Audit Office because I was interested in society, and encouraged me to apply. I sort of applied on a whim, but then I made it through the various application stages, and I ended up in an accountancy graduate scheme.

I probably went into that role thinking I had it all sussed. I didn’t feel I needed to be the best at it, so I thought I could just do enough to get through the exams and it would be fine. But it was so difficult, in fact one of the most difficult years of my life. Graduate schemes want 150% from you, so I was studying and taking exams as well as doing the work. Probably from week two I had doubts about accountancy as a career path for me, but there was so much momentum – for example, in week four I had two exams which I had to pass or I’d be asked to leave – so I didn’t have the brain capacity to think about whether it was right or wrong for me, I just had to focus on the work. I took 11 of 12 exams, and passed 10 of them. I stayed for just over a year, and then I left. It was definitely valuable to learn about financial reports and business models, which I’d had no understanding of as a researcher. But it wasn’t the right step for my career, and it was so full-on that afterwards I had to take time out to recover.

So for about three years I was focusing on personal rather than professional development. For me, that meant a mixture of travel and working in a café start-up, and temping. I wanted to keep things light, and not take on anything too new and serious, because I wanted the next step to be more considered. I did a lot of networking as part of the career exploration process, and took an interest in other people’s jobs and what they liked about them. That was essentially the first time I was reflecting on what I wanted and liked in a job. And during those conversations, a friend of mine inspired me. She studied drama/dance as her degree and now works as an office manager in a media company. When I asked her how she chose her path, she told me she’d thought about what she liked in a job, and she realised she didn’t want to have to wear stiff smart clothing, she wanted to work in a pretty environment with nice lighting and furniture, and she wanted people to thank her lots and appreciate her. And that’s what she gets from her current job. It was a bit of a revelation for me, as it was the first time I’d ever encountered someone thinking about the more day-to-day factors involved in being at work.

As she is one of the happiest people I know in their job, I tried to take the same approach of thinking about what I wanted day-to-day. I realised I didn’t want the output of my work to be a report. And I started to recognise that my strengths were in interpersonal understanding, and that I wanted to work with people. I wanted to work more flexibly than a post-doc – I didn’t want my field and skillset to be so narrow that it dictated where in the world I could work, I wanted flexibility to live life on my terms. I wanted a sense that my skills were innate in some way, they were part of me. I didn’t want to have to have technical expertise, for example, using a very specific piece of machinery. All of this led me to gravitate towards coaching, but I didn’t want to take a coaching qualification without knowing it was the right next step for me. And then I met someone who worked at UCL Careers, and she told me about her job as a careers consultant, which entailed one-to-one guidance and groupwork. There was a qualification involved, which definitely wasn’t a draw for me as I didn’t really want to commit to another qualification, but the employer would pay for it, and I got to start the work and see if I would like it before embarking on that study. It sounded good, and so here I am!

What does an average day look like?

It’s really varied, and often depends on the time of year. Seeing students is a big part of the role – offering guidance and practice interviews. In the Autumn and Spring terms delivering workshops is a key feature, so is the planning and preparation for those workshops. I also work closely with academics and academic departments, figuring out what they want for their students. In our team in engineering there’s also someone who looks after employer engagement and someone who looks after sourcing internships and vacancies, so I’m often liaising with them and informing my work through their knowledge. I also work closely with colleagues on projects, which can take various forms, from putting together new events to thinking about online content.

What are the best things about the role?

I find working with students massively rewarding. I enjoy the conversations we have, I feel like I learn a lot, and I feel I have (usually) helped them move on by the end of our conversation, so there’s a tangible immediate value to my work. Thinking back to my days as a post-doc, it would take a long time to see the impact of what I was doing, so it’s refreshing to see the impact there and then, and especially reflecting on my own journey, I know this career thinking is important. I also enjoy being in a university setting, where I get to work with so many stimulating ideas; whether that’s the most innovative teaching and coaching methods, or the engineering innovation that impacts employment and careers for the students I support. I also enjoy working with my colleagues and getting to be creative in how we approach the task of helping students.

What are the challenges?

The role is incredibly varied, which I really like, but I also know it’s a very different way of working to when I was in research or accountancy. I have to do lots of different things well now, so there’s a lot of time and quality-management involved. I’m no longer focusing on one thing and making it perfect. Instead I need to get lots of things done in a way that’s high quality but efficient, and allows space for a broad range of tasks. There’s also a lot of managing a busy calendar, and managing it around lots of colleagues who are also managing busy calendars themselves.

Is your PhD useful in the role?

A PhD isn’t essential for the role, although I have several colleagues who also have PhDs. There are definitely some similarities between my research years and this role; I get to work with ideas, and I have a fair amount of autonomy, I’m always learning and can take a scholarly approach to my work. And an ability to research means you can stay up to date in innovations in teaching, coaching, employment and recruitment processes etc. Having the PhD experience also helps me when working with students considering moving to PhD study, or with PhD students thinking about what to do next.

What’s the progression like?

It’s great to be in this sector as it feels there are loads of opportunities to progress in different directions, which is refreshing compared to my time in academia. For me personally, I really enjoy our core practices of guidance and coaching, so that’s something I want to develop, and perhaps take that on as an area of expertise if I move to Senior Careers Consultant level. There are also ways to move upwards if you want to take on managerial roles – Team Leaders, Deputy Heads, Heads. And in Higher Education more widely there are lots of opportunities to move around and support students and/or research in different ways, and movement between roles isn’t unusual.

Some careers consultants will go freelance at some point and work with private clients. I have considered having more of a portfolio career in that way, and if I did ever want to do that, this is a great platform to start from. So I feel very positive about the opportunities, and I feel very strongly that I have control over what I want my role to look like in future. I’m the one getting to choose.

Tips for researchers

If you think you might like to be a careers consultant, get involved in talking to the careers team at your university, and see if there are any opportunities for you to work shadow, or to get involved in helping at events. Also take on opportunities to support students, such as teaching or personal tutoring or supervising.

And for researchers thinking of leaving academia more generally, in my experience of talking with current researchers and those who’ve left, I notice there can often be a sense of disempowerment –a feeling they don’t have any useful skills and they won’t be valued outside of academia. But there are so many opportunities for you to be valued in the world. So I would encourage you to take each and every chance to explore what else might be out there for you.

Close

Close

Dr Ardavan Alamir has a PhD in Physics and now works in cyber-security at G-Research. We caught up with Ardavan to hear about his role and career journey so far.

Dr Ardavan Alamir has a PhD in Physics and now works in cyber-security at G-Research. We caught up with Ardavan to hear about his role and career journey so far. Dr Keith O’Brien earned his PhD in Experimental Psychology from UCL, and now works as the Global Behavioral Insights Lead for Simply Business. Keith kindly spoke to us about his role and his transition into industry.

Dr Keith O’Brien earned his PhD in Experimental Psychology from UCL, and now works as the Global Behavioral Insights Lead for Simply Business. Keith kindly spoke to us about his role and his transition into industry.

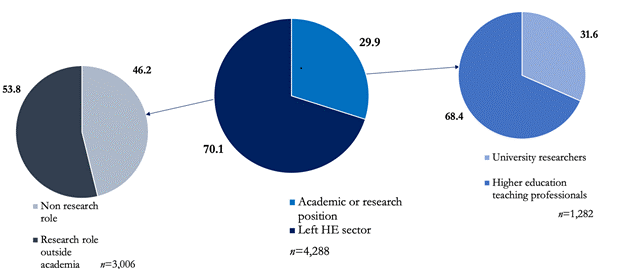

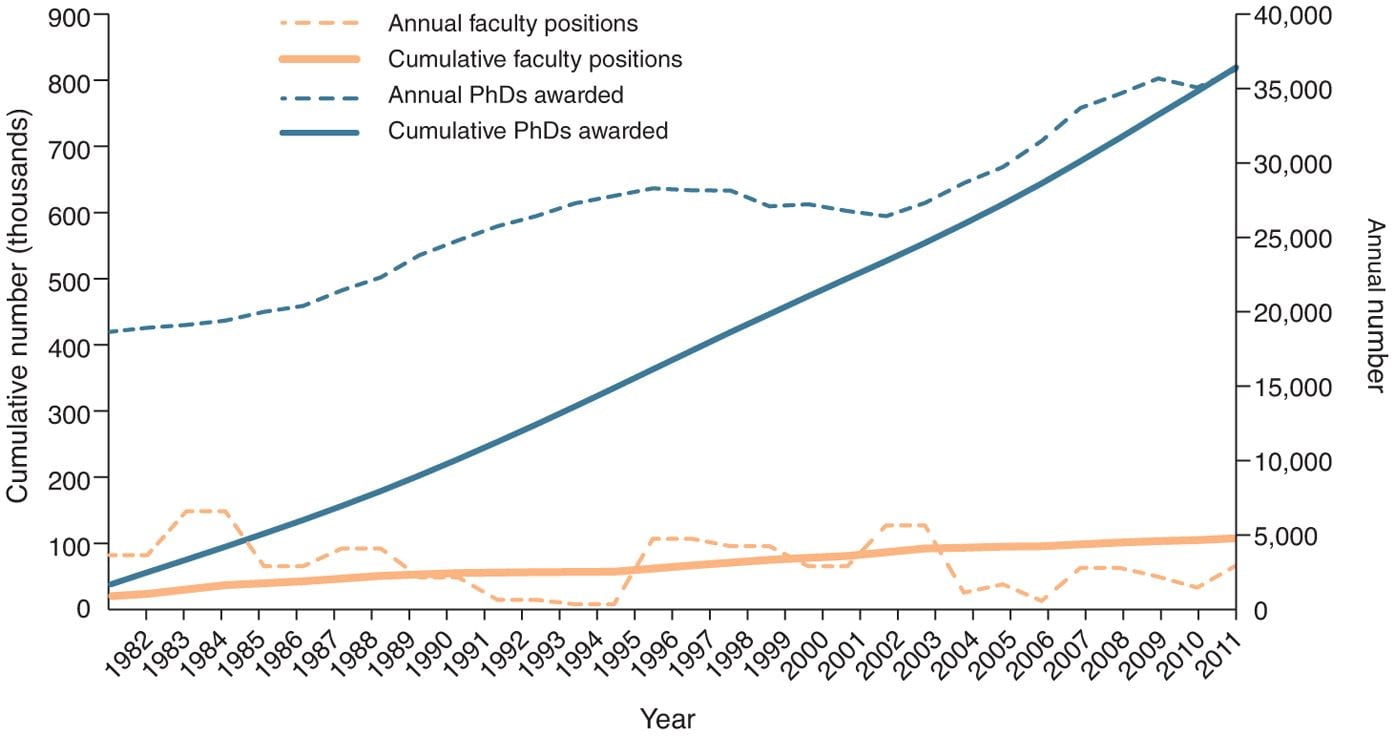

Figure taken from Schillebeeckx et al’s 2014

Figure taken from Schillebeeckx et al’s 2014