I’m intrigued about your pathway into this topic.

I’m intrigued about your pathway into this topic.

Well it converged from two directions. I’ve been an allotment holder for 15 years, experimenting with a low-input, high-productivity method where you work alongside natural systems, not against them. That was a hobby, something I loved doing. Professionally, I was teaching international relations theory, which is a lot about how order can emerge from within a system itself.

In the debate following my first book, The New Imperialism, I discovered general systems theory, which tries to identify what’s common to all systems: they have a capacity to self-regulate, but they can also go haywire. So I began to understand that the ecological problem and the threats to human society are not two separate challenges which just happen to face us simultaneously; rather, we can study them – and look for answers – in an integrated way.

I addressed this in my 2012 book The Entropy of Capitalism, but at that more general level it was easier to write convincingly about all the bad stuff that was happening, than about solutions! The only way to get to grips with positive solutions was to take a very concrete topic and run with it. With Sustainable Food Systems, this all came together.

Please tell us a bit about the process, from initial conception, to publication

Together with my colleague Yves Cabannes I started teaching a Masters module on Urban Agriculture, and there were also a few small community food-related action research projects. This suggested a lot of ideas which I felt somehow needed to be written down.

But the project implies an unusual form of knowledge, drawing on both natural and social sciences. While general systems theory was a help, I had to be respectful to the integrity of each specific discipline – soil science, anthropology etc. – even where I don’t have specialist training. To ensure the research was solid, I embraced the peer-review process at several levels. I started with a conference paper, delivered in Paris in 2012, and then split it into five journal articles and book chapters, all exploring different aspects of food-systems issues. While I received much important feedback from the reviews on these papers, I was also myself doing quite a lot of peer-reviewing for journals. And I could trust the peer-review system for the quality of research in the leading scientific journals which I was citing.

At the same time, the ‘new paradigm’, also implies deeper issues of fundamental world view. In this sense, knowledge (or maybe we should say wisdom) should not be reduced to academic research. The traditional/indigenous spirituality doesn’t see a distinction between nature and society anyway, it understands that our minds are part of nature, and correctly sees farming as intrinsically rooted in the wider ecosystemic context. In this sense, visioning sustainable futures is also a return, to a more authentic way of apprehending the world and our place in it.

Finally, the project implied a different publishing model. Though there were enquiries from conventional publishing, I quickly rejected this when I realised that the form of publication must reflect the content: the book is about emergent order, self-organisation, commons regimes, peer-to-peer, grassroots research … therefore it had to be open-access. I was delighted that UCL Press was thinking the same way.

What’s your take on organic food? Are you advocating it?

There are two issues here. First, from a consumer angle, of course there are dangers from pesticides or loss of nutrients, which are rightly emphasised, but at the end of the day you might just say mainstream agriculture successfully feeds the world and the risk of changing it is too great. So I would rather approach the question from the production angle: the main thing wrong with conventional farming is that it destroys the complex soil ecosystem and ultimately the soil itself, and therefore the risk of not changing it is too great. We have a window of opportunity while there’s still enough food around. That’s why the issue is urgent.

Secondly, ‘organic’ can often seem a negative definition, i.e. we limit ourselves by renouncing chemicals, which makes it seem like we’re farming with one hand tied behind our back. I’d rather emphasise what we are opting into: a whole new world of biomimicry and self-organisation … that’s why I sometimes prefer a term like Natural Systems Agriculture. Besides, the problem isn’t just chemicals, but a lot of other stuff: excessive ploughing, monocropping … Much of this is about how we face risk, because natural systems spontaneously evolve in response to shocks, and become stronger in doing so.

Surprise me with something unexpected you encountered in researching this book.

A couple of paradoxes, which are in fact closely linked:

[1] When looking for cutting-edge examples of the new paradigm in action – learning from nature, self-assembly and self-healing, not trying to control systems too much – I found them in areas like industrial design and materials science; farming in contrast, which you might expect to be our interface with nature, is still horribly conservative and stuck in the old ways. Wonderful research is being done, about soil systems for example, but translating this into an innovative, high-productivity, totally biomimicked farming practice: that’s not yet the mainstream, it’s still very peripheral.

[2] The countryside is so heavily depleted by herbicides, pesticides and monocropping, that cities are potentially havens for nature to regenerate itself: this has been beautifully demonstrated by green roofs, for example, and is potentially very encouraging for a programme of greening the city. We might even pioneer the new paradigm here!

The book has an optimistic vibe, because it’s about solutions, and as you’ve said, some elements of ‘paradigm shift’ already underway. So what’s blocking it? And in particular, how do you interpret the recent Right-wing nationalist backlash.

In the book, I paraphrase a quote from Lenin, about the ruling system being dragged against its will into a new social order. The shift in world politics towards the nationalist Right shows the system digging its heels in, frantically resisting the implications which its very own development has unleashed. That’s the aspect internal to society. But then there’s the environmental context: climate – plus soil-degradation and species-loss – forms the backdrop to everything.

So why is the nationalist Right addicted to climate denial? Because if we take climate seriously, we’d have to face up to the social conditions demanded by resilience: decentralised capacity, peer-to-peer networks, modularity, non-monetary exchange, commons regimes. These are all evident in today’s food-related social movements – seed-sharing for example. The issue is inevitably political: a new ‘order’ is a self-organised, emergent order. That’s what scares the ruling interests.

So what about this term ‘food sovereignty’? That sounds nationalistic in a way…

I think it was always more about community autonomy. But in a deeper sense, I take your point: we must dare to be normative, not just describe a movement like food sovereignty, but discover what it should be. A lot about the ‘old’ food sovereignty was resisting the extreme neo-liberal agenda of ‘free’ trade and its disastrous implications for food, and that was all very necessary, but it was only a phase. In the book I try to place this in a much broader historical context. You have millennia of resistance against exploitative agrarian systems, then against colonialism and imperialism, then against the ‘Green Revolution’ of the Cold War; at an English level, there is an unbroken legacy: the peasants’ revolt, the Diggers of 1649, early 19th century Chartists, the Land and Freedom movement of the 1970s, and some inspiring contemporary stuff. If the ruling agenda is today shifting away from ‘free’ trade, the enduring issues of commons and land rights haven’t changed.

At the same time, today’s food sovereignty must also face up to new challenges. What has gone haywire (in society and its relations with nature) has been a narrowing, homogenisation, simplification. Physically, this is seen in the shrinking variety of crops being cultivated, in the strains of each crop etc.; socio-politically this is seen in intolerance, xenophopia, the narrowing of discourses. If that is permitted, we will have a system (in food, in society) which fractures and disintegrates in the face of shocks.

So if we are to respond to this threat, I would say – prolonging the book’s argument – that if political liberalism has in a sense destroyed itself by hitching itself to economic neo-liberalism, then the good things which used to be (very imperfectly) identified with liberalism must be regenerated on a new basis: tolerance, pluralism, what I’d call a ‘new cosmopolitanism’ … in essence a diverse system which can produce innovation from anywhere and which – when it faces shocks – will get stronger.

The movement over land and food can be a flagship for this. Today, the academic and science community is trying to resist the attacks of obscurantism, but can’t do this alone: it needs mass allies. This is precisely what the land/food-related struggles – of peasants, indigenous peoples, the urban masses – can supply; the academic world has important knowledge to offer, but it will also be itself transformed by discovering a new social relevance.

In these ways, researching the book, I got some kind of glimpse of a new world coming into being. It’s exciting to feel part of this.

Sustainable Food Systems: The Role of the City is available to download for free here.

Filed under Guest Posts, Open Access

Tags: Anthropology, Archaeology, Architecture, Books, Climate Change, Development, Food, Geography, Open Access, Society, Sustainability, Topical

No Comments »

On 18 May 2017, Niels Brügger, Professor of Internet Studies and Digital Humanities at Aarhus University in Denmark, and co-editor of The Web as History, delivered the third lecture in the UCL Centre for Digital Humanities annual Susan Hockey lecture series. With a focus on archiving, the lecture investigated the different types of digital media and explored how each type can be used for scholarly purposes.

On 18 May 2017, Niels Brügger, Professor of Internet Studies and Digital Humanities at Aarhus University in Denmark, and co-editor of The Web as History, delivered the third lecture in the UCL Centre for Digital Humanities annual Susan Hockey lecture series. With a focus on archiving, the lecture investigated the different types of digital media and explored how each type can be used for scholarly purposes. Close

Close

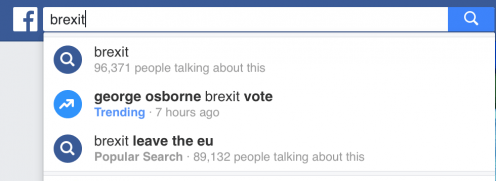

One of the common claims made about social media is that it has facilitated a new form of political intervention aligned with the practices and inclinations of the young. Last week I attended the launch of an extremely good book by Henry Jenkins and his colleagues called By Any Media Necessary which documents how young people use social and other media to become politically involved, demonstrating that this is real politics not merely ‘slacktivism’, a mere substitute for such political involvement.

One of the common claims made about social media is that it has facilitated a new form of political intervention aligned with the practices and inclinations of the young. Last week I attended the launch of an extremely good book by Henry Jenkins and his colleagues called By Any Media Necessary which documents how young people use social and other media to become politically involved, demonstrating that this is real politics not merely ‘slacktivism’, a mere substitute for such political involvement.