Three ways institutions can support research partnerships

By Guest Blogger, on 4 November 2021

By Sam Mardell, UCL Strategic Partnership Manager (AHRI); Amit Khandelwal, UCL Senior Partnership Manager (South Asia); and Monica Lakhanpaul, UCL Pro-Vice-Provost (South Asia)

The increasing globalisation of people and economies, the devastating impact of COVID-19 on societies across the world, the multifaceted problems caused by climate change and the ongoing global commitments to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) make this a crucial time to generate discussion on strengthening partnerships underpinned by first-class research.

The increasing globalisation of people and economies, the devastating impact of COVID-19 on societies across the world, the multifaceted problems caused by climate change and the ongoing global commitments to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) make this a crucial time to generate discussion on strengthening partnerships underpinned by first-class research.

Some of the highest profile scientific and research achievements have been accomplished through partnerships between UK universities and other institutions worldwide. The UCL Ventura-CPAP breathing aid and the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine are just two recent high-profile examples of what can be achieved through collaboration of this kind.

Yet, these partnerships are the exception — generated at a time of crisis — rather than the rule. We undertake partnerships, with all the additional effort and time that these involve, because they generate better outputs and outcomes. How can we create an environment in our institution where collaborations are encouraged and can flourish?

A successful research collaboration harnesses the strengths of each partner for greater impact. For example, academics can provide the evidence base for decision-making, but without industry partners to take ideas through to production, or the involvement of the third sector to ensure that solutions really meet societal needs, then good ideas remain just that — ideas.

For the purposes of this discussion, we define a positive partnership as one that achieves the explicitly stated goals of the research, while allowing all partners to learn and advance throughout the period of collaboration and beyond.

Research partnerships invariably work because of interpersonal relations. There is a great deal of literature on how to nurture these partnerships; frequently these are based simply on two individual academics who get along with one another.

Institutions do also play a role in generating an environment that supports and values academic collaborations. Here we outline the three key areas of institutional support to the creation and successful implementation of research partnerships.

1. Train academics in partnership building:

Academics are experts in their field — but that does not automatically generate the soft skills or knowledge needed to create a successful collaboration. There has been much discussion over the past few years about the need to recognise systemic and structural power inequalities and ensure that they do not feature in research relationships. Assume that you will provide the skills without learning from your collaborators, and you both miss the additional benefits collaboration can bring and belittle your partners’ contribution to the success of the project.

Institutions can provide a basic understanding of the dynamics and sensitivities that might influence how collaborators view the UK through provision of a basic history of the country and any historical inter-country linkages. This is particularly relevant when working with partners in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where unequal and lop-sided benefits frequently advantage the more powerful partners in a collaboration.

Signposting on how to navigate working intercultural collaborations can support academics in developing contacts who can advise on cultural sensitivities and expected behaviours. This can be immensely helpful in developing early relationships. Awareness that different cultures will approach a problem in a distinct way is essential, with differences in approach often generating better outcomes. This is equally valid for collaborations across the public-private-people-policy sectors and between larger and small universities as it is for national-international collaborations.

University policy can help to avoid the obviously exploitative activities — such as using in-country staff only for fieldwork, denying shared authorship opportunities, or ethics dumping — that characterised the relationship of a fair proportion of academics from the richer nations working in low-resource settings in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

For a truly positive partnership, thought should be given to addressing how academic partners ensure that local or traditional knowledge and expertise is a recognised, valued and rewarded part of collaboration. Good partnerships also have leaders with a suite of skills additional to their individual scientific expertise; this requires training on working collaboratively to help ensure partnerships work well and generate innovative and impactful results.

2. Provide resources to nurture nascent partnerships

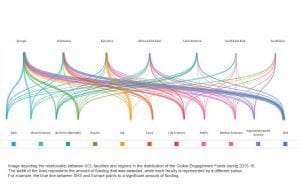

Open communication is one element of a partnership that has been radically reconstituted and reformed over the past year during the COVID-19 pandemic, with Zoom and Teams calls now the norm. Whilst academics have been denied the opportunity to hold face-to-face conversations with partners overseas over the past year, virtual communication has put overseas partners on an equal footing with local colleagues. The provision of small travel grants and seed corn funding — such as those provided by UCL’s Global Engagement and Grand Challenges funds — can facilitate the initial conversations needed to begin building the trust and mutual respect that are so vital to positive partnerships.

3. Create an enabling institutional environment

Longer-term collaborations, which span multiple projects and years, require time, patience and understanding of the priorities and constraints of another organisation or individual. Copious amount of coffee, tea and food — sprinkled with an appreciation of another culture and sharing personal experiences — are the building blocks of relationships. Yet the current academic system generates rewards for being a Principal Investigator: for individuality and being first author or lead institution. Institutional recognition of the time investment needed to develop partnerships — listening to partners, respecting their challenges, and understanding the context within which they are working — is needed when assessing academics’ achievements at appraisals or promotion boards. This requires a shift from a quantitative review of academic achievement based on impact factors and grant income to one that recognises that nurturing partnerships can pay dividends in co-creating and delivering appropriate solutions and enhanced positive impact.

Partnerships are all about relationships: equitability, having a flexible mind-set and trust. If you get this right, you have the key ingredients to ensure that your project or activity will be a successful and impactful one.

But partnerships also require institutional incentives and structures that do not penalise academics for collaborative activity. Harnessing a variety of intellect and expertise, innovation and skills focussed on clearly defined goals can ensure that, through the power of partnerships, research generates positive outcomes and impact for all involved.

About the authors

If you would like to know more about developing partnerships and how we can help you, please contact us:

Sam Mardell is the Strategic Partnership Manager for UCL’s relationship with the Africa Health Research Institute (AHRI), South Africa. She also co-Chairs the UCL LMIC Research Operations Group.

Professor Monica Lakhanpaul is Professor of Integrated Community Child Health at the UCL GOS Institute of Child Health and Pro Vice Provost for South Asia. Her research promotes citizen science using structured and participatory methods to co-design interventions for the advancement of population science.

Dr Amit Khandelwal is Senior Partnership Manager (South Asia) within the Office of the UCL Vice-Provost (Research, Innovation & Global Engagement).

This piece was originally posted on the UCL Disruptive Voices blog.

Close

Close