Second TA workshop

By Clive Young, on 9 November 2011

In the second of our TA meetings over a dozen attendees explored the AUA professional behaviours and how they relate to both the day-to-day work of participants and the digital literacies identified in the first workshop. A full report will follow. Clive also introduced various certification options and the idea to start the certification process early in 2012, rather than wait until the second half or the project. Lorraine discussed the eight case study areas we wanted to concentrate on and asked for volunteers to participate and even lead these ‘mini-projects’. The eight areas are;

Support of UCL students overseas

Support of UCL students overseas- Distance Learning .

- VLE e.g. Moodle / Moodle 2

- Assessment and feedback

- Quality Assurance

- Student tracking from student to alumni

- Communications and social media

- Internal operations – e.g finance.

In addition we want to look at the whole issue of CPD, what kind of certification is appropriate and how CPD can be integarted into workloads and review processes.

Distributed literacy in the digital department

By Clive Young, on 20 October 2011

Early last year the ESRC/EPSRC Teaching and Learning Research Programme published ‘Digital Literacies’ (Gillen and Barton 2010) useful overview of the theoretical background. It traced the conceptual evolution of the term from its origin as a synonym for ‘IT skills’ through the addition of ‘soft skills’, in an academic context mainly criticality and evaluation and on to the Web 2.0 notion of the student as a consumer/creator/collaborator. The latest manifestation revolves around the idea literacy as a ‘situated practice’ i.e. it is intimately linked to the specific context of use and cannot (should not?) be considered in isolation.

Early last year the ESRC/EPSRC Teaching and Learning Research Programme published ‘Digital Literacies’ (Gillen and Barton 2010) useful overview of the theoretical background. It traced the conceptual evolution of the term from its origin as a synonym for ‘IT skills’ through the addition of ‘soft skills’, in an academic context mainly criticality and evaluation and on to the Web 2.0 notion of the student as a consumer/creator/collaborator. The latest manifestation revolves around the idea literacy as a ‘situated practice’ i.e. it is intimately linked to the specific context of use and cannot (should not?) be considered in isolation.

Most of the discussion concerns student literacies, about how the individual acquires digital expertise in a disciplinary domain and within a specific teaching context but that this ‘literacy’ contributes (among other things) to the transformation of the student into a skilled practitioner, ready to take her place in an increasingly ‘technologised’ professional world.

Nonetheless the authors detect a distinct shift from the original formulation of digital literacy as ‘the skillset of the individual’ towards a more modern model of literacy as a ‘social practice’. As the authors put it, “a single act of digital literacy’ is founded upon a network of practices with sociohistorical antecedents” and it only has meaning “if it has a relation to others’ understandings and activities”.

Although the original TDD proposal focused on the CPD and the portfolio-building of the individual we emphasised the development of a community of practice as a dynamic resource network providing an external perspective as well as a source of expertise. Reading Gillen and Barton I suspect this goes even further. The digital department is itself both a social practice and an active process. We cannot ultimately look at the literacies of one the TAs alone; we should think of distributed digital literacies across the department. As the literacies of TAs improve, what is the effect of the other participants in the departmental social practice; the students and particularly the academics? Can the students own literacies be enhanced by interacting with a ‘switched on department’? Will academics, relieved of basic digital management have the time and inclination to engage more fully with online activities? What effect could this have on course design?

But that is what makes TDD so interesting, as Gillen and Barton explain

“Digital literacies are always dynamic – in part because technology is perceptibly developing so fast in front of our eyes – but also because human purposes continue to develop and are reshaped by collaboration. This is the moving backcloth for the current explosion of creativity in digital literacies that makes this such a fascinating arena”.

The AUA’s ‘professional behaviours’

By Clive Young, on 20 October 2011

At the AUA CPD Pilot Group Networking event in Manchester today among a lively group of CPD ‘champions’ who are implementing the AUA’s ‘professional behaviours’ framework in a range of projects to aiming to develop professional services staff.

At the AUA CPD Pilot Group Networking event in Manchester today among a lively group of CPD ‘champions’ who are implementing the AUA’s ‘professional behaviours’ framework in a range of projects to aiming to develop professional services staff.

The framework derives from a HEFCE-funded AUA programme that started in 2008 which attempted to build on a number of existing professional and management standards to develop a ‘common language’ that could be used to describe the CPD needs of university administrative staff. After a sector-wide consultation the framework emerged as a range of nine ‘professional behaviours’ such as ‘delivering excellent service’, ‘embracing change’ and ‘working with people’, usually displayed as a circle.

The behaviours aim to describe how a person does a job, so conceptually sits between the job description and the person specification. Each behaviour has a definition describing how it influences the individual, her relationship with others and in the context of the wider organisation.

The AUA projects, some in their second year, were using the framework in a variety of ways; as part of the recruitment process, for CPD planning, and frequently as part of a reorganisation process. The Digital Department is looking at the AUA framework as a way of ‘unpacking’ the skills of our teaching administrators, to suggest a development path and to help alignment with the AUA portfolio certification process. Although funded by JISC, we were invited to join the wider AUA network initiative and we met representatives of at least one project who was trying something similar, although with a different group of staff.

To familiarise ourselves with the framework we used the behaviours as a ‘coaching wheel’, to rate our confidence against each, which we wanted to develop and (especially revealing) what our respective institutions expected of us. A useful and engaging tool and we look forward to using it with our TAs to identify their activities and skills.

Digital literacies and identity

By Clive Young, on 12 October 2011

In the second leg of our JISC Digital Literacies tour last week our TDD team went to Bristol for the Developing Digital Literacies workshop. Again a very interesting event, with all the workshop materials available online. The main emphasis was on why digital literacies are important – mainly impacts of digital media on knowledge and the new demands on education. We discussed ‘ways of knowing’ , ‘graduate attributes’ and how universities are investigating this strategically. There was an excellent presentation by Charlotte Fregona of London Metropolitan University on their SLiDA case study. The surprisingly-overlooked link between staff literacies and student literacies was explored and I was impressed by London Met’s Minimum Standards for Digital Learning and Teaching and their excellent Elearning@LondonMet pilot portal.

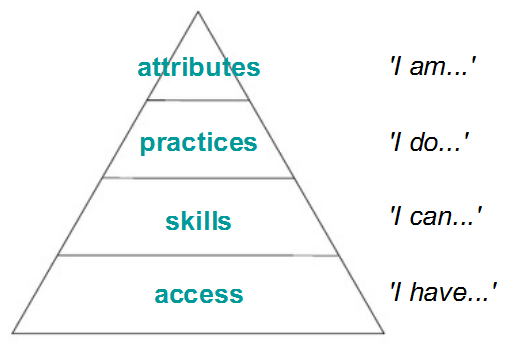

One area I thought fascinating from a TDD perspective, though, was the link between digital literacy and identity. From the initial stages of TDD we understood that for our colleagues the project framework could consolidate the idea ‘Teaching Administrator’ as an accepted professional support role with some level of status. Individuals and organisations would recognise and identify with the job description. The framework itself would describe a development path to a desired set of professional attributes. We hope the framework becomes a benchmark for both self-evaluation and aspiration. Helen Beetham presented the digital literacies ‘stages of development‘ model (right) she had developed with Rhona Sharpe. She had intended it as a Maslow-style hierarchy but came to realise the flow wasn’t always upwards. If people could self-identify as wanting a set of professional attributes that make up a professional identity they could ensure access acquire skills and develop practices. We are hoping that will happen with our TAs.

One area I thought fascinating from a TDD perspective, though, was the link between digital literacy and identity. From the initial stages of TDD we understood that for our colleagues the project framework could consolidate the idea ‘Teaching Administrator’ as an accepted professional support role with some level of status. Individuals and organisations would recognise and identify with the job description. The framework itself would describe a development path to a desired set of professional attributes. We hope the framework becomes a benchmark for both self-evaluation and aspiration. Helen Beetham presented the digital literacies ‘stages of development‘ model (right) she had developed with Rhona Sharpe. She had intended it as a Maslow-style hierarchy but came to realise the flow wasn’t always upwards. If people could self-identify as wanting a set of professional attributes that make up a professional identity they could ensure access acquire skills and develop practices. We are hoping that will happen with our TAs.

As the discussion developed we also wondered if some academic identities actually excluded digital literacies i.e. “as a professional academic I’m simply not interested in that online stuff”. As identity is deeply important to people it may explain why some have in the past reacted so strongly against apparently innocuous uses of technology.

Digital literacies and ownership

By Clive Young, on 12 October 2011

Last week our TDD team spent an extravagant amount of time at JISC events as part of our membership in their Digital Literacies programme. In the Programme Start-up in Birmingham meeting (left) we gave an ‘elevator pitch’ for TDD and met the other 11 projects in the programme. We learned that there was only a one in seven success rate for proposals and I think we all felt quite privileged to be included.

Last week our TDD team spent an extravagant amount of time at JISC events as part of our membership in their Digital Literacies programme. In the Programme Start-up in Birmingham meeting (left) we gave an ‘elevator pitch’ for TDD and met the other 11 projects in the programme. We learned that there was only a one in seven success rate for proposals and I think we all felt quite privileged to be included.

Listening to the other 11 elevator pitches we picked up some fascinating ideas but also felt that TDD was slightly dissimilar to the others. While all were innovative of course we generally felt had a very clear target audience (I don’t think any of the others were working so specifically with staff), a defined and existing community to work with, an unusually focused set of literacies to focus on and in our certification model both a concrete outcome and clear a success indicator.

We also learned much about benchmarking current practice and also evaluating to detect change but what struck me was the broader discussion about the context of digital literacies and where TDD fits in.

The first issue is one of ownership. The main model of digital literacy so far if one of personal ownership. This is not surprising as the model has derived from students’ literacies which by definition have to be both portable (able to be decontextualised from the programme of study) and transferable (able to be applied) to work and further study. Thus one definition of digital literacies goes “the sum of capabilities an individual needs to live, learn and work in a digital society”. However the TDD model of literacy, although still ‘owned’ by the individual – hence our emphasis on portfolios and certification – is both contextualised and integrated. Thus we can begin to think of complementary literacies within a stable enterprise, in our case a department. If we have highly digitally literate TAs how does this affect the literacy practices and requirements of the students and academic staff that surround them? I suspect this question will arise repeatedly throughout the project.

NUS “New Technology in Higher Education” Charter highlights admin role

By Clive Young, on 11 October 2011

The National Union of Students’ Charter on Technology in Higher Education, published in August this year aims to set out “best practice for the use of technology in higher education, for teaching & learning and how technology can improve the student experience“. The idea is that students and their respective student unions will use the Charter to make sure technology is high on the institutional agenda so that “graduates are equipped and ready for the 21st century environment“.

The National Union of Students’ Charter on Technology in Higher Education, published in August this year aims to set out “best practice for the use of technology in higher education, for teaching & learning and how technology can improve the student experience“. The idea is that students and their respective student unions will use the Charter to make sure technology is high on the institutional agenda so that “graduates are equipped and ready for the 21st century environment“.

The 10 points of the charter cover; clear ICT strategy, staff development, training and support for staff and students, accessibility, online administration, linking technology-enhanced learning and employability, investment in using technology to enhance learning and teaching, research into student demand and finally that technologies should enhance teaching and learning but not be used as a replacement to existing effective practice.

Online administration is of course an interesting focus with regard to our The Digital Deprtment project. More specifically the Charter says “Administration should be made more accessible through the use technology, including e-submission, feedback and course management“. It continues “The use of technology in institutional administration will simplify and improve assessment, feedback, registration and module selection. Technology should also be utilised to support effective communications within institutions for both students and staff“. Very much the emphasis of the project and good to hear these views expressed so clearly from representatives of the student body.

Supporting Learners in a Digital Age

By Clive Young, on 26 September 2011

Not surprisingly much of the work on digital literacies in higher education has focused on students. JISC have recently published Supporting Learners in a Digital Age, a briefing paper largely based on their high profile ‘Supporting Learners in a Digital Age’ (SLiDA) project. SLiDA explored how nine different institutions are helping students use digital technologies effectively in their studies, and preparing them to live and work in a digital society. Part of the briefing paper is a “a strategy for digital capability“. This states in short:

Not surprisingly much of the work on digital literacies in higher education has focused on students. JISC have recently published Supporting Learners in a Digital Age, a briefing paper largely based on their high profile ‘Supporting Learners in a Digital Age’ (SLiDA) project. SLiDA explored how nine different institutions are helping students use digital technologies effectively in their studies, and preparing them to live and work in a digital society. Part of the briefing paper is a “a strategy for digital capability“. This states in short:

- Thriving in the digital age demands the confidence to respond to complex and changing circumstances, rather than mastery of specific systems.

- It helps to have a framework of core principles.

- Shared frameworks are key to a strategic approach, but examples of good practice are important to guide curriculum renewal in different subject areas.

- Digital skills should not be bolted on to existing provision. Rather, the institution needs to renew its core practices in the light of new digital challenges and opportunities.

Alhough aimed at students these apply equally to staff skills. Indeed in the strategy it is recognised that “teaching staff skills are critical to students’ experience and developing confidence with technology”. How can this be achieved? “In addition to general workshops and training opportunities, staff benefit from embedded experts such as e-champions and specialist professionals. They need opportunities to share practice with colleagues in both scholarly and informal settings.” In other words The Digital Department altnough adapting the focus very much builds on and extends the ideas of Supporting Learners in a Digital Age.

Project background – Why ‘Teaching Administrators’ (TAs)?

By Clive Young, on 20 September 2011

As the complexity of teaching and learning in Higher Education has grown we have seen the emergence of a cadre of academic managers and administrators, perhaps 30,000 individuals across the sector (Morgan 2011). While this trend is lamented by some as an increase in ‘pen pushers’ (e.g. Grimston 2011), there is also a growing recognition (e.g. Gordon and Whitchurch 2011) that especially in increasingly technologically ‘blended’ learning environments administrators and other support roles have a very positive contribution to make to the student experience.

As the complexity of teaching and learning in Higher Education has grown we have seen the emergence of a cadre of academic managers and administrators, perhaps 30,000 individuals across the sector (Morgan 2011). While this trend is lamented by some as an increase in ‘pen pushers’ (e.g. Grimston 2011), there is also a growing recognition (e.g. Gordon and Whitchurch 2011) that especially in increasingly technologically ‘blended’ learning environments administrators and other support roles have a very positive contribution to make to the student experience.

As a consequence in recent years a range of responsibilities have shifted from academic to support staff. In many departments Teaching Administrators (TAs) now have wide responsibilities for admissions, quality management, programme and course coordination and planning, VLE course management, student advice etc., and digital literacy underpins all these activities. TAs are also closely involved in the student feedback processes e.g. via questionnaires and Staff-Student Consultative Committee meetings and have a pivotal enabling role in supporting distance learning.

The growth of new roles is closely connected to the growing use of digital technologies. Like most universities, at UCL this is now policy: “the use of online technologies is an essential component of the way in which students access and engage with the curriculum at UCL” (Institutional Learning and Teaching Strategy 2010-2015). It is becoming clear that for this high-tech, high-touch vision of the modern university to be realised the digital literacies of support staff must be developed as a strategic asset and in developing this project we recognise the partnership between academic and non-academic staff required to achieve the highest standards in our academic mission.

The ambition of The Digital Department is therefore to professionalise the digital literacy of education administrators in order to enhance the teaching and learning environment. This is not simply the development of a specific group of staff; we see the digital literacies of students, academic colleagues and TAs being interconnected via the digital learning environment (see diagram top right).

References:

Grimston, J. (2011) Pen-pushers outnumber professors at university The Sunday Times, 10 April.

Morgan, J. (2011) A starring role beckons, Times Higher Education, 14 April.

Gordon, G. and Whitchurch, C. (2009) Academic and professional identities in higher education: the challenges of a diversifying workforce, London, Routledge, see also summary paper.

TDD at the AUA

By Clive Young, on 19 September 2011

Clive Young, representing the project, spoke alongside Myles Danson of our funders the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) at the AUA West Midlands One-day Conference in Oxford on 14 September. The theme was how we can use technology to make our work easier and more efficient. The session showcased JISC’s continuing work with AUA including a new £1.5 Million programme to explore the skills needed by administrators and managers to work effectively in modern high-tech environments.

Clive Young, representing the project, spoke alongside Myles Danson of our funders the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) at the AUA West Midlands One-day Conference in Oxford on 14 September. The theme was how we can use technology to make our work easier and more efficient. The session showcased JISC’s continuing work with AUA including a new £1.5 Million programme to explore the skills needed by administrators and managers to work effectively in modern high-tech environments.

Clive introduced The Digital Department project and explained how we will be working closely with the AUA to establish a sector-wide certification framework.

This was followed by a discussion with the participants (university administrators from throughout the region) to find out what outcomes they would find useful. These were their ideas

- Be ambitious “look at everything differently”

- Involve students – what would they like (demand), also make use of their experience

- Link to job specifications (standardise for all roles), performance review,

- How to promote institutional responsibility and role

Issues

- Don’t ignore the emotional side – people become defensive if they think they are ’illiterate’

- Issue of ‘letting go’, attitudes and processes that work (albeit inefficiently)

- Make learning ‘organic’ – don’t over-formalise

- “Make it safe to have a go”

- Try webinars – expert advice

- Mentoring, buddies

- Guides – too many things to learn, how to find “right tool for job”

- Consider ‘live’ workshops or action learning groups – get people out of the immediate environment and solve problems.

Myles finished the session by providing a useful list of JISC resources to help administrators including;

- Resources to help manage university business www.jisc.ac.uk/supportingyourinstitution

- A review of five tools for university administrators

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/inform/inform31/ResourcesAdministrators.html - Introducing our toolkits:

www.jiscinfonet.ac.uk/infokits - The JISC Digital Literacies Programme

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/developingdigitalliteracies

Report from the first TDD workshop

By Clive Young, on 2 September 2011

The notes are now available from our first TDD Workshop on 16 August 2011. The aim of the event was to introduce the project to a group of UCL teaching administrators and do some initial brainstorming (a method known as ‘knowledge spaces’) with the group around the areas of;

The notes are now available from our first TDD Workshop on 16 August 2011. The aim of the event was to introduce the project to a group of UCL teaching administrators and do some initial brainstorming (a method known as ‘knowledge spaces’) with the group around the areas of;

- digital literacies i.e. what tools we use and what skills we need

- what kinds of areas the TDD should investigate (e.g. mini-project)

- what kind of skills training and development we should consider.

The results were fascinating and perhaps surprising. We were struck by the number of processes, systems and applications TA need to learn and apply.

The report is avilable Notes from workshop 16 Aug 2011 v2 (PDF 5pp).

Close

Close

JISC

JISC