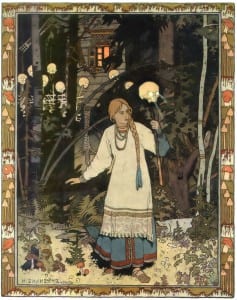

Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov

By Sarah J Young, on 28 February 2013

Traditional tales open a window onto the riches of Russian culture, finds guest poster Robert Chandler

A good anthology has a shape of its own; it is a work of art in its own right. Usually, though, it seems best to allow this shape to emerge gradually, not to impose a shape on the material too quickly.

My first idea for this anthology goes back seven or eight years. My previous anthology, Russian Short Stories from Pushkin to Buida, had received good reviews and was selling well. My editors at Penguin Classics asked if there was any other project I would like to embark on. I at once thought of a collection of magic tales. My very first publication, in 1978, was a translation of Andrey Platonov’s retellings of traditional Russian tales and my second publication was of tales from Afanasyev (the Russian equivalent of the Brothers Grimm); both books had been long out of print, so here was a chance to bring these skazki back into circulation. And Platonov is, to my mind, the greatest of all twentieth-century Russian writers, so I usually make the most of any chance to draw attention to him.

At first I meant the anthology to begin with Afanasyev and end with Platonov. Then, however, I started playing around with some passages from Pushkin’s verse folk tales. Somewhat to my surprise – I never take anyone’s ability to translate Pushkin for granted! – these passages turned out well. First I translated some lines from the tale about the Golden Fish; since the original is unrhymed, this was not too difficult. Then I attempted the last stanza of ‘Balda’. If I could get that to be clear, sharp and memorable, I thought I would probably be able to manage the rest of the poem. The last two lines were the most difficult. Once they came right, the rest followed more easily:

The poor priest

presented his forehead

for three quick flicks of a finger.

The first

flung him up to the ceiling.

The second

cost him his tongue.

The third

plastered the wall with his brain.

And Balda said,

with disdain,

‘A cheapskate, Father, often gets more

than he bargained for.’

‘Balda’ is written in rhyming couplets, but in lines of greatly varying length. There is an improvised quality to the tale; what is striking about it is its energy, not its polish. To reproduce this jazzy energy, it seemed best to use a somewhat freer form than that of the original; my rhyme pattern, unlike Pushkin’s, is entirely irregular – and some lines do not rhyme at all.

Pushkin was one of the very first Russian writers to take a serious interest in Russian folklore. Once I was confident of my ability to translate these skazki, I knew that the book should begin with Pushkin, that it should include a large selection of oral tales collected by Afanasyev and other folklorists, and that it should end with my translations of Platonov. There has always been interplay in Russia between high culture and folk culture, so it seemed right to include both genuine oral folktales and literary retellings. (more…)

Close

Close