Dr Phil Cavendish at Grad London

By yjmsgi3, on 29 March 2016

Dr Philip Cavendish spoke at the recent GRAD Eisenstein exhibition on the introduction of colour film to Soviet cinema.

The overarching title of the Gallery for Russian Art & Design’s (GRAD for short and based in Little Portland Street, London) series of public lectures this Spring is a play on the well-known slogan, ‘A Cinema, Understood by the Millions’. This became associated with Soviet cinema of the 1930s.

Courtesy of GRAD

Since the drawings of Sergei Eisenstein are the subject of the exhibition currently being curated at GRAD, it might be worth pointing out that the title also makes reference to the title of a newspaper article which Eisenstein published alongside Grigorii Aleksandrov in early 1929. Entitled ‘Eksperiment, poniatyi millionam’ (An Experiment Accessible to Millions), this was published in the film journal Sovetskii ekran to accompany the release of the film Staroe i novoe (The Old and the New) – also known as General’naia Linia, which they had directed together.

By suggesting that colour cinema was an ‘experiment understood by very few’, I don’t mean that Soviet audiences experienced conceptual confusion in relation to the phenomenon of colour. Instead, it is that the complexity of the scientific processes that underpinned the development of colour technology was generally grasped poorly. This is true of the direct consumers of film culture, the vast majority of film critics and correspondents who reported on that culture, the senior managers and employees of Soviet film studios and the bureaucrats that were responsible for the film industry as a whole.

This lack of comprehension had dire, if not tragic, consequences for some of those involved in colour-film production in the Soviet Union. It also produces significant challenges for the film historian who seeks to understand the phenomenon and its implications for the development of Soviet cinema and Soviet culture more broadly.

Courtesy of GRAD

The reasons for being interested in this subject are nevertheless various and compelling.

Firstly, very little has been written about the early period of Soviet colour film. Indeed, it is not widely appreciated even among Soviet film specialists that the first experiments dated from the mid-1920s and early 1930s.

Secondly, even among those Russian film historians who have written about colour in the 1930s and 1940s, there is very little awareness of the huge importance attached to this phenomenon by Party leaders and film-industry officials, to the extent that the ambition to acquire a viable colour process was deemed an urgent political and ideological task.

Stalin himself was impressed by the three Walt Disney Technicolor animations that were screened as part of the First Moscow International Film Festival in 1935. He went on to monitor developments in colour cinema reasonably closely.

The notebooks of Boris Shumiatskii, (head of the Main Directorate of the Film and Photo Industry and responsible for organising regular film screenings at the Kremlin), reveal that the Great Leader was shown and commented upon screenings of various materials filmed in colour between 1935 and 1937.

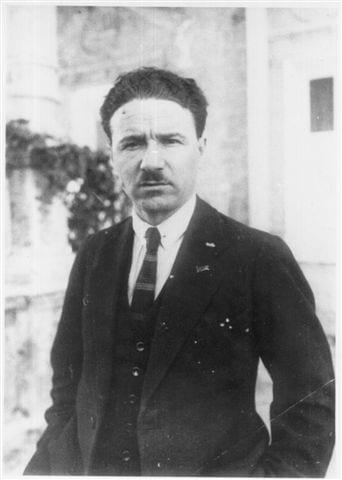

Boris Shumyatskii in Teheran 1924

Source: Wikicommons / Ekaterina B. Shumyatsky

These included footage of the 1934 May-Day parade and several sequences from a three-colour animation which was being filmed by Aleksandr Ptushko at the Mosfilm studio. The notebooks also record Stalin requesting regular updates on the progress of Soviet colour-film production and impressing upon Shumiatskii the ‘urgent task’ of developing a home-grown colour-film technology.

Stalin’s interest in colour film was for two reasons, according to official announcements in the film press of this period. Firstly, the desire to equal, if not outshine, US technological dominance in this particular domain and secondly, the desire to promote colour cinema as part of an emerging official discourse that emphasized the importance of entertainment, pleasure, joy and general happiness.

Two physical-culture parades that took place on Red Square on June 24th 1938 and August 18th 1939 were documented in colour, which highlights the ideological importance of colour film for Stalin’s government.

It is difficult to imagine two more prestigious commissions. These parades were meticulously choreographed. They involved tens of thousands of sporting representatives and athletes from different Soviet republics marching past the Kremlin with Stalin and other members of the Party leadership in attendance. These parades embody the energetic promotion of physical fitness and sporting prowess during the 1930s. Thanks to the involvement of the ‘Prepared for Work and Defence’ programme since March 1931, they also reflected the importance attached to general military preparedness.

Unlike other state celebrations, the physical culture parades were specifically designed to be colourful events, with the costumes of the participants, some of them clearly drawing on the national traditions of the republics, bright and vibrant, if not flamboyant. Foreign observers at the time, for example the American ambassador Joseph Davies, were struck by the gaiety of these spectacles.

Thanks to the availability of colour-film technology, the parades could be captured on celluloid in vibrant hues for the first time and presented to a public which would not have been able to witness them first-hand, due to the exclusive nature of the events.

It was probably with these parades in mind, that in 1940 Grigorii Aleksandrov declared that: ‘Colour is essential for the expression of joyfulness and happiness. Our festivals are bright and saturated with colour. All our folk art dazzles with the richness of its palette. Colour is an essential element in the multinational art of the USSR’.

‘Unexpected Eisenstein’ runs at GRAD until 30 April.

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the SSEES Research blog, nor of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, nor of UCL.

Close

Close