FRINGE Centre blog series: ‘G’ for Grey Zones

By tjmsubl, on 4 January 2016

In the fifth of our series of blogs celebrating the launch of the UCL SSEES FRINGE centre, Udo Grashoff considers the letter G – for grey zones.

Today, after the criminalisation of illegal housing in Western European ‘heartlands’ of squatting such as the Netherlands and Great Britain, there is not much squatting or illegal housing left. In England, for example, squatting in residential properties is now a criminal, rather than civil, offence. In recent years, the troublemakers and mucky pups have been shooed away from many European metropolises. Is squatting now merely a historical quirk? And does it hold any interest for the present? If the answer is yes, this is perhaps due to two reasons.

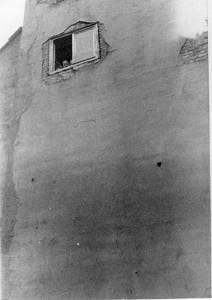

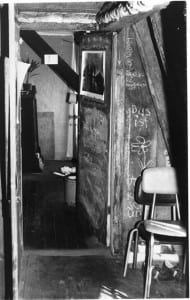

Firstly, it is interesting because there are still discoveries to be made. Believe it or not, during the 1970s and 1980s, there was illegal housing on the other side of the ‘Iron Curtain’, too. Despite the tight control in communist dictatorships, thousands of inhabitants of socialist countries undermined the state’s claim to power. In principle, only state authorities or enterprises allocated flats. In practice, it was possible to find alternative ways. There were grey zones of silent (in)action, negotiation and/or compromise. So far, very little is known about the nature and the scope of illegal housing in socialist countries such as Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia or the Soviet Union. Why and how was it possible under these repressive regimes at all? Which factors enabled people to occupy empty flats in cities such as Leningrad, Leipzig or Prague? How important were legal frameworks, and difference in practices of their enforcement such as eviction? Can we identify a ‘socialist’ pattern of illegal housing?

What we know is that informal housing in Eastern Europe was less politicised, rather driven by practical need, than in the West. While many West European squatters considered themselves to be part of some social movement, illegal housing in socialist countries was confined to clandestine and individual action. In most cases single flats were occupied instead of houses. The purpose was not to establish an alternative to the ‘system’, but simply to find a flat (though, of course, in some senses this was an implicit critique of the system).

The second reason why squatting is of interest, and not only for historians but also for sociologists, lawyers, architects, political scientists, artists and others, is that neoliberal governments did not make it disappear, at least not globally. Informal housing is one of the practices of ‘beating the system’ or circumventing its constraints that has become a ‘weapon of the weak,’ fighting for their right of survival. While a process of elimination has taken and is still taking place in many European countries, there are still millions living in favelas (South America), shanty towns (South Africa), gecekondus (Turkey) and other forms of illegal or ‘grey’ housing settlement. While the term ‘squatting’ is often used here, too, is it just a misleading analogy or can we learn something when we compare illegal housing in quite different contexts? Is it useful to compare European squatters and shanty towns in countries such as Pakistan, Kenya or Vietnam? It’s worth a try.

Our first step into the dark (or better: grey) zone of informal housing is scheduled for June 2016: a workshop with scholars studying illegal housing in Eastern and Western Europe, sponsored by the Small Grants Scheme of UCL European Institute. The workshop will address a number of relevant aspects (such as legal frameworks, conducive factors, motivations of the squatters, interactions with state institutions and the public sphere, forms of cohabitation). One goal of the workshop is to collect information, another aim is to organise a dialogue between experts on the Eastern and the Western perspective. Was illegal housing in the East a relatively autonomous phenomenon, or just a tame and belated copy of Western ‘guiding culture’? How did these practices, originating under quite different property situations, interact?

It is worth highlighting the intrinsic ambiguities of illegal housing that can be observed in Eastern and Western Europe respectively. While one prevalent narrative considers squatting a political alternative to capitalism, one can argue that in many cases it just paved the way for gentrification. Apparently illegal housing in Western Europe was much more diverse than the cliché of the anarchist squatter might suggest. Dutch sociologist Hans Pruijt has identified five ‘configurations’ of squatting: severe housing deprivation, seeking alternative housing, conservation of houses, political action and entrepreneurial activities. It would be interesting to revisit our knowledge about informal housing in socialist countries in light of this typology. Apart from that, a similar ambiguity can also be observed in the East. Informal housing can be understood as an act of resistance. But didn’t the informal utilization of a dilapidated flat, often after extensive repairs, solve a housing problem and thereby stabilise the shortage economy, too?

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the SSEES Research blog, nor of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, nor of UCL.

Close

Close